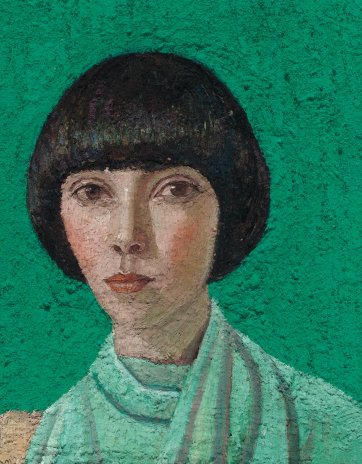

Une Femme Amoureuse, Self portrait as Mireille Mathieu, 2022 Yvette Coppersmith

For Yvette Coppersmith, self-portraiture is a genre that allows her many things: to carve out a place in the world, to reflect her influences outwardly, to place her body at the centre of formal, artistic experiment, to reckon with gender, art history, its canon. But at the heart of her work is a sense of performance, a trying on of images and ideas. She is chameleon-like – dressing up and down, segueing through time, adopting and adapting personalities.

Let’s start here – with Une femme amoureuse, self-portrait as Mireille Mathieu, a finalist in the 2022 Darling Portrait Prize. Poised, alert, set against different, faceted greens. It was a work that happened by chance, a costume bought for a cancelled shoot. But art always finds a way to be made. There are coincidences – a new haircut, a later realisation of its similarity to that of Mathieu, a French singer who Coppersmith’s mother once played on repeat. These things work in, manifest unexpectedly, art and life are always intersecting.

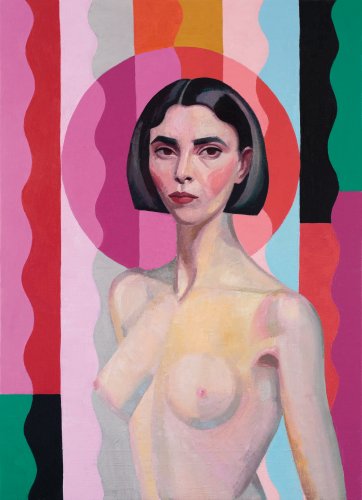

1 Self-portrait, ochre shirt, 2018 Yvette Coppersmith. Photo by Matthew Stanton. © Yvette Coppersmith. 2 Nude Self Portrait, after Rah Fizelle 2016 by Yvette Coppersmith.

‘They all have stories,’ she says. But they aren’t always readily apparent. Self-portrait is a painting that began ten years before it was finished. Paint applied, scraped off, reapplied again and again. She observes that she ‘changed so much during the making. Each time I approached the canvas it was a matter of arriving at an image of the self in that moment’. Eventually the work was finished in a frenzied morning. Ten years in two hours. ‘Ultimately the deadline decides for you – you work up until the moment. Each painting is defined by various constraints.’

As a portrait painter you need a figure. Coppersmith’s choice to use herself in her work is in some sense a pragmatic one – there are no hours to keep, no wages to pay. Aside from the constancy of her outward gaze, which implies her process of working from the mirror, the mechanics of her paintings are invisible. Yet all of them are staged, compelled by a sense of play, of dressing up, of trying on. Within the safety of the studio possibilities open up. There is freedom to explore mood and psyche. She describes the impetus and outcome as ‘trying to be in the world in an imaginative way’.

1 June 2020, Chanel earrings, 2020. 2 Self-portrait with chroma abstraction, 2019. Both Yvette Coppersmith.

Photo by Matthew Stanton © Yvette Coppersmith

The stillness of the painting, the image fixed, is something she has sometimes worked against. In Self-portrait, ochre shirt, her arms are held in dynamic form, mirroring a modernist background reminiscent of artists Anne Dangar or Dorrit Black. She regards it as an origin point, the beginning of work in which she has actively engaged with performance and dance. Recent abstract paintings, shown under the title Presage, are inspired by movements first made in silk costumes, loops and swirls becoming forms within the works.

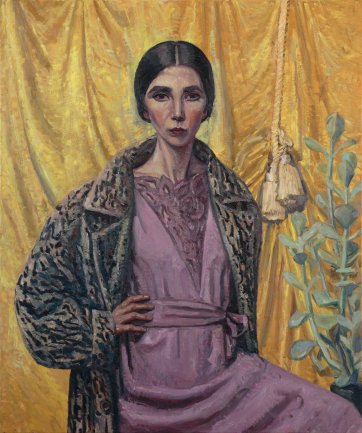

1 Self-portrait, after George Lambert, 2018. Photo Tim Gresham. © Yvette Coppersmith. 2 Self-portrait with still life (Sanné Mestrom, Soft kiss maquette), 2018. Photo by Matthew Stanton. © Yvette Coppersmith. Both Yvette Coppersmith.

Some of Coppersmith’s paintings are efforts to engage with other artists, to place herself in proximity to them. Self-portrait, after George Lambert, or Nude self-portrait, after Rah Fizelle are as much homages to those artists as attempts to insert herself within the male-dominated canon of Australian art. The matter of gender is always present, an overarching concern.

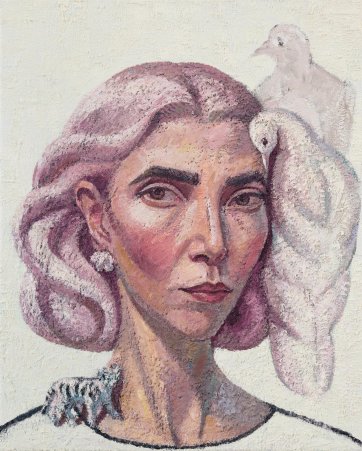

1 Self-portrait with ruby headdress, 2018. Photo by Matthew Stanton. © Yvette Coppersmith. 2 Self-portrait with dove, 2017. Photo Tim Gresham. © Yvette Coppersmith. Both Yvette Coppersmith.

A series of portraits made from ‘rust and Autumn colours’ channel the painters Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff. But ‘these are much more feminine,’ she states, the gestural impasto of the latter transformed into unfathomably delicate peaks of paint. They reflect a key moment in which she moved away, decisively, from her photo realist background; from high-finish outcomes to something ‘process driven’ in which the time it took for paint to dry meant she was never immediately sure of the outcome. She recalls ‘good days, really long days when flow states’ occurred, during which she moved through several paintings, resolving successive formal and compositional elements. She realised through this process that given time and continual engagement – ‘eventually the image will work’.

Amid the charged atmosphere of the studio, the sense of possibility, is also isolation. Coppersmith has prioritised her work over everything else and admits the emotional cost is great. The advantage is that she is ‘immersed in the practice … but I don’t know anyone else who has spent so much time alone’. Self-portrait with still life (Sanné Mestrom, Soft kiss maquette) was made compulsively in one session. The maquette was placed in the painting as she craved human company. The ‘painting becomes a way of problem solving,’ she says, the making of art a form of company in and of itself.

1 Self-portrait with egret, 2018. 2 Self-portrait, 2011–22. Both Yvette Coppersmith.

Photo by Matthew Stanton © Yvette Coppersmith

Coppersmith asks: ‘How does an artist find a visual language which is the best vehicle for the energy that they are feeling?’ Often it is by gathering what is closest to her – objects chanced upon, taken up as talismen, loaded signs and symbols all finding their way into her work. Self-portrait with dove is one such image. Astonishment and gloom on Donald Trump’s election were embodied in the form of a perfect bird found dead beside the road. In her work it is restored to life, beautiful and transcendent. ‘Sometimes you’ll be feeling dark, heavy energy. But you can make something really beautiful from that.’ It is an energy that she both wields and embodies, magnificently.