Growing up, I didn’t know I was Torres Strait Islander. I didn’t know my heritage or my culture because my mum was separated at birth, placed in an orphanage and adopted out. She spent the larger part of her life searching for family, for culture, for belonging and identity. Like her, my sense of belonging and identity was disrupted due to this cultural disconnection. It wasn’t until we moved to Queensland and started going to First Nations art workshops with the local mob that we were reconnected to both culture and family.

I always felt a sense of shame when I was younger, especially through my teenage years and early twenties, because I couldn’t tell you where I was from or who I was. I didn’t know how or have the proper skills to trace my bloodline or history. It was through the help of other First Nations people, especially in the arts sector, that I was able to put the pieces together. This was often through spending countless hours in yarning and weaving circles, talking and making art. These circles are safe spaces, leveraged on trust and mutual respect. I was taught how to make string, to weave and to prepare different types of fibres while learning about who I was, hearing stories and piecing together a fractured sense of self.

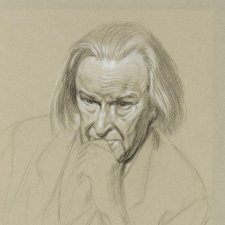

Traditional modes of portraiture are often equated with the idea that identity is connected to individuality, expressed through likeness. Alongside this, the desire to represent the character, disposition and inner self appeared within portraiture to further express identity. Indigenous portraiture, however, often does not follow the conventions of western portraiture in depicting the face or physical likeness. Within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, the concept of collaboration is a fundamental feature of identity. Through storytelling and skill sharing, intergenerational knowledge and history is passed from one generation to the next and forms the basis for understanding the world around us, with art often acting as the vehicle. Art objects and practices are inseparable from everyday life and constitute one of the central sites of cultural knowledge embedded in ceremony, daily use and storytelling. Indigenous culture, as a whole, is relational with collective perspectives. The self is understood through our relationships to one another, and to all living and non-living things including the waterways, the mountains and the deep saltwater oceans, through to the vast celestial realms. It is these relationships to the world around us that form the foundation of Indigenous ideology and culture. This movement between the land and each other defines ways of being, ways of doing and ways of knowing ourselves. Therefore, identity is embedded in the nexus between the self, others and the land.