There were a number of Australians at the Society of Antiquaries of London for the presentation of the 2018 William MB Berger Prize for British Art History. Angus Trumble was there as Director of the National Portrait Gallery, organising gallery for the exhibition Dempsey’s People, and publisher of its handsome, prize-winning catalogue, and I as curator and author. The Australian High Commissioner, the Hon George Brandis kc had been invited. By happy chance, Justine van Mourik, Director of the Parliament House Art Collection, was visiting London at the time, and expatriate Professor Jos Hackforth-Jones, Director of the Sotheby’s Institute, also attended. After the presentation, the Aussie party began to break up before heading to the Berger dinner at the Garrick Club, just half a mile down the road. In the melée of coat-gathering, Angus disappeared; but as we trudged along Piccadilly in the London late autumn cold, a black Rolls Royce cruised slowly past, Angus waving regally at us from within.

A lift with the High Commissioner was the kind of opportunity Angus could not resist. High style, edging into pomp. An Important Person. The opportunity to schmooze. A handsome enamelled badge. A flag. Above all, an anecdote – to be retailed at a dinner party, an opening, a bar, or in one of his regular and voluminous digital newsletters, public diaries eagerly devoured by friends around the world.

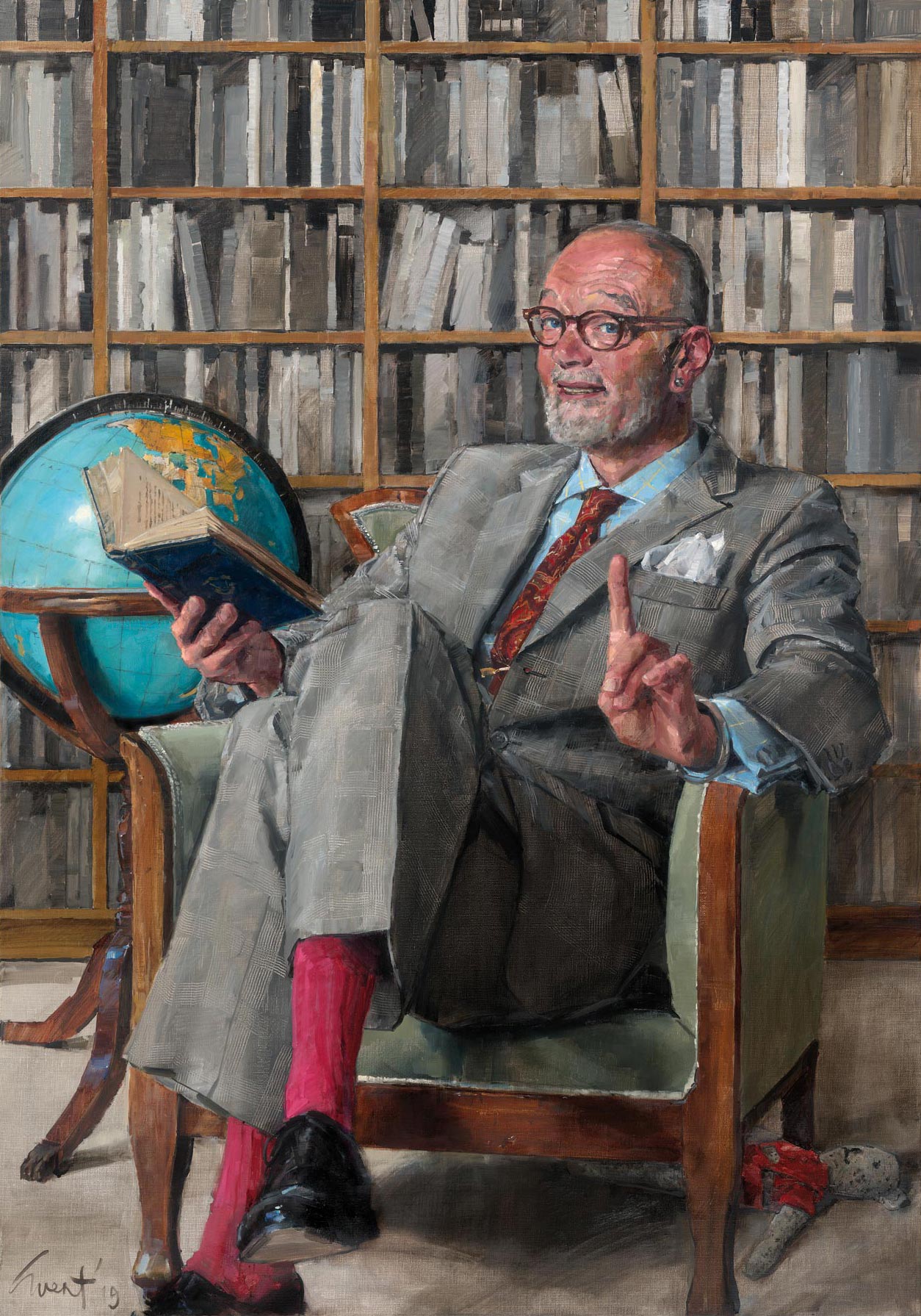

Since his sudden death from a heart attack in October 2022, those who he left behind have been revisiting and rediscovering the manifold qualities of his character displayed in those blogs and other correspondence: (in no particular order) observant, self-deprecating, witty, precise, quirky, fluent, charming, erudite, opinionated, dashing, ironic, playful, sensible (in the 18th century sense, not the 20th), sparkling … These were among the qualities that made him such a dear and delightful friend and colleague. They were also what helped to make him a wonderful, original scholar, curator, writer and gallery director.

Angus Trumble faha was born in Melbourne in 1964, son of Peter and Helen Trumble and youngest-by-eight-years of four brothers. Trumble minimus was educated at Melbourne Grammar School (private school agony being somewhat abated by his being awarded the Barry Humphries Prize for Liberal Arts) and the University of Melbourne. He was recently quietly thrilled to be made a Fellow of his beloved Trinity College; his Fellow’s stole was draped over the lectern at his funeral. On graduation, Angus spent time in Rome and as an intern at the Peggy Guggenheim Foundation, Venice, before returning to Australia and four years as civilian aide to Dr J Davis McCaughey ac, Governor of Victoria; in residence at Government House, Melbourne, he honed his capacity for diplomatic niceties and discreet naughtiness.

But beauty called; following further study at the Bibliotheca Hertziana in Rome and a Fulbright Scholarship to the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, in 1996 Angus was appointed Associate Curator (later Curator) of European Art at the Art Gallery of South Australia. There he produced (inter alia) the marvellous Love and Death: Art in the age of Queen Victoria, and from there originated the first of his two slim but rich best-selling non-fiction scherzi: A Brief History of the Smile (2005) and the irresistibly subtitled The Finger: A Handbook (2010). From 2003 to 2014 he was Curator of Paintings and Sculpture at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven; there his exhibitions included studies of Benjamin West, James Ward and Francis Wheatley, as well as the stunning Edwardian Opulence: British Art at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century; for Yale art history students he was also a much-loved teacher.

Angus returned to Australia in 2014 to take up the reins of the NPG, which he held firmly in hand from 2014 to 2018. His engagement here was directorial, and he can certainly take CEO credit for the NPG’s three funky entries in the international Museum Dance-Off, and for overseeing the exhibition 20/20, a celebration of the Gallery’s 20th anniversary through 20 new portraits of notable Australians. A rare specimen of that highly endangered species, the scholar-director, he also drove several brilliant acquisitions, including a portrait of the young William Bligh attributed to John Webber, an early self portrait by Arthur Boyd, and Graham Sutherland’s Helena Rubinstein in a red brocade Balenciaga gown. Typically, this last prompted what is likely Angus’ last book (unless the manuscript of his long-gestating late British Empire island comedy of manners/spy/murder mystery should surface); his curiosity about Madame’s early, Australian years has resulted in a new biography, to be published in 2023 by La Trobe University Press.

He wrote beautifully; after leaving the NPG he was appointed Senior Research Fellow at the National Museum of Australia, where his online Endeavour Reflections deftly unpacked the early journal entries of James Cook, Joseph Banks and Sydney Parkinson, and the mixed meanings of HMB Endeavour in Australian waters.

Beautifully, and with scholarly rigour. A little while ago, I sent Angus an extract from Steven Miller’s marvellous episodic history of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, one dealing with the Gay Governor of New South Wales, whom I made the mistake of calling ‘William Lygon, 7th Earl of Beauchamp.’ His response was swift, and typical – in the gentleness of its rebuke, the sternness of its etiquette-stickling and the irrepressibility of its enthusiasm: ‘It’s Earl Beauchamp like Earl Spencer and Earl Mountbatten and Earl Attlee (whereas there are no Viscounts *of* anywhere, but there is The Knight of Glyn). I must find out why this little fancy took hold.’

Sadly, that’s one little mystery he will now never get around to solving for us.