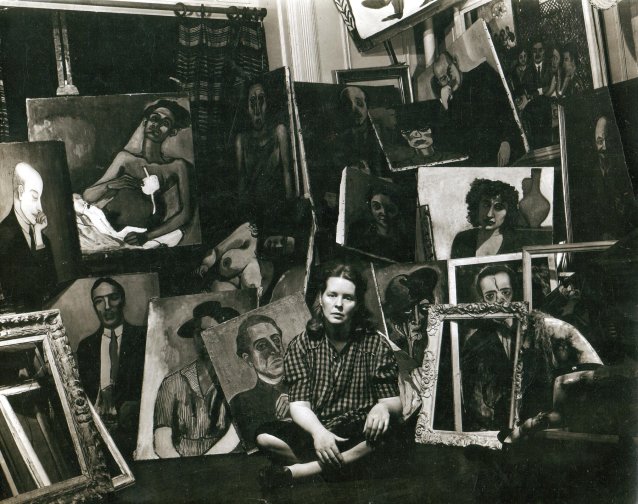

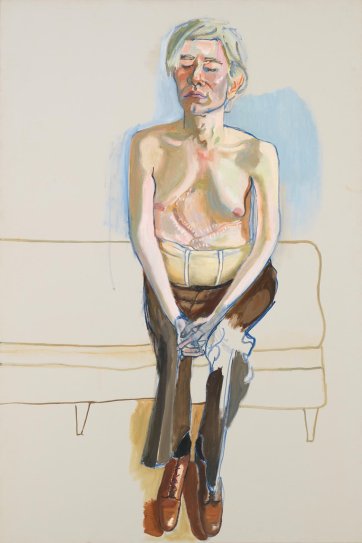

Throughout her long life, the American artist Alice Neel’s gaze was astute, unsentimental and compassionate. She documented seemingly everyone she came into contact with: her lovers, her neighbours in New York City, her children and other people’s, family, friends; couples, be they gay, straight or transgender; workers, writers, artists, students, homeless men and women, feminists, performers, poets, pregnant women, shrinks and singers – but she only rarely painted herself. ‘I tried to capture life as it went by – art records so much, the feeling, the beliefs, the changes,’ she wrote. In 1980, at the age of eighty, however, she unveiled a self portrait. Naked in the striped, blue chair where so many of her friends had sat before her, as with all of her portraits flattery played no part in her vision: her belly is swollen and her breasts sag, but her expression is direct and unabashed. One of the many startling things about this painting is its reminder of how rarely – especially in museums – we see images of women comfortable in their skin. In a culture that worships at the altar of youth, Neel looks at us, grey haired and bespectacled, unselfconscious about her lack of clothing. One hand brandishes a paintbrush, while the other holds a rag. The composition hums with life: the bright green and orange floor, the jaunty blue of the chair and the light-filled room are as vital as the woman herself. Neel worked on the picture for five years. ‘Frightful, isn’t it?’ she said in a 1983 Artforum interview. ‘I love it. At least it shows a certain revolt against everything decent.’

Although she died almost four decades ago, Neel’s muscular, vivid portraits – or, as she preferred to call them, ‘pictures of people’ – are as relevant, as moving and as influential as ever. ‘I have painted life itself right off the vine,’ she said, ‘not a copy of an old master with new figures inserted – because now is now.’ Her concern for her fellow humans – many of them migrants, working class, or ostracised because of their race, gender or sexual orientation – ran deep in her veins but it wasn’t something that she observed coolly from a distance. Despite her great capacity for joy, tragedy and hardship marred her life: she endured the death of two of her children, two suicide attempts, abusive relationships, poverty and decades of being ignored by the art establishment.

Born in 1900, the fourth of five children in an impoverished middle-class family in Pennsylvania, she liked to pronounce: ‘I am the century.’ Decades later she remembered: ‘Being born I looked around the world and its people fascinated and terrified me.’ After working as a clerk for three years and studying art at night school, she enrolled in the fine art program at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. She discovered she had the two qualities she deemed essential for the life she intended to live: ‘You know what it takes to be an artist? Hypersensitivity and the will of the devil. To never give up.’

In 1925, after a brief courtship, she married the Cuban painter, Carlos Enríquez. The couple moved to Havana, but it was a struggle for Neel to balance the demands of her husband’s disapproving parents and her work an artist. She and Carlos would walk the streets, looking for people to paint. Beggars, Havana, Cuba (1926) is an intimation of the power of her portraits to come: a study of a stooped and veiled old woman sitting beside a man who holds himself erect, it’s a portrait of pride and resilience, not deprivation.