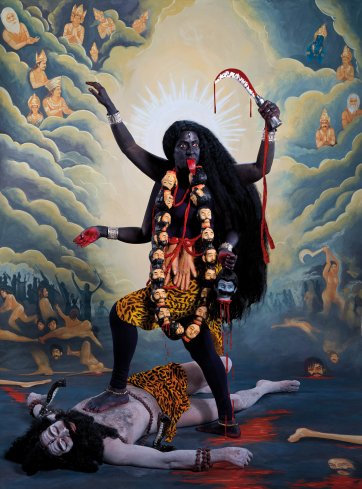

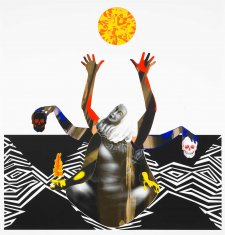

Marcia Langton by Brook Andrew is a signature work in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery. The multi-armed form is central to the force of this portrait, a device that has been used to different effect by artists in assorted times and places. While reasons for its use vary, the desire to convey a consciousness in flux is a common one. In the case of Marcia Langton, the mutable experience of being human is given intricate form in what Langton herself describes as a ‘meta-statement’. Each of its elements and symbols richly and singularly meaningful, the work is configured to elicit momentum, a life in flow. At once it transmits its distinctive dynamism, while powerfully deconstructing expectations of stasis that have characterised portraits of Aboriginal peoples.

When I first encountered this portrait on the Gallery wall, its jostle of movement stirred me, drawing me in to look closer at the assembled pieces. Unencumbered by a glass cover, its variably printed and painted, layered paper is more accessible to the eye. Paper has an impermanent quality, especially in relative terms here at the National Portrait Gallery. The surrounding portraits are photographs of people encased behind glass, or paintings of people, who, in contrast with this incarnation of Marcia Langton, seem stilled within paint. In Marcia Langton, the vulnerable, transient pieces float upon the coursing, trapezoid-like shapes of a Wiradjuri river background. The combination of their placement and materiality – differently angled, crafted paper cut-outs of the body, head, limbs, skulls, fire and faceted sun – invites wonder about how the patterned and coloured pieces might look if re-arranged. I want to move them around, as if galvanising a daunting, dancing marionette. It occurs to me that the multi-armed figure form is ideal for unifying so many elements because it evokes creativity and fluidity, and because of its potency.