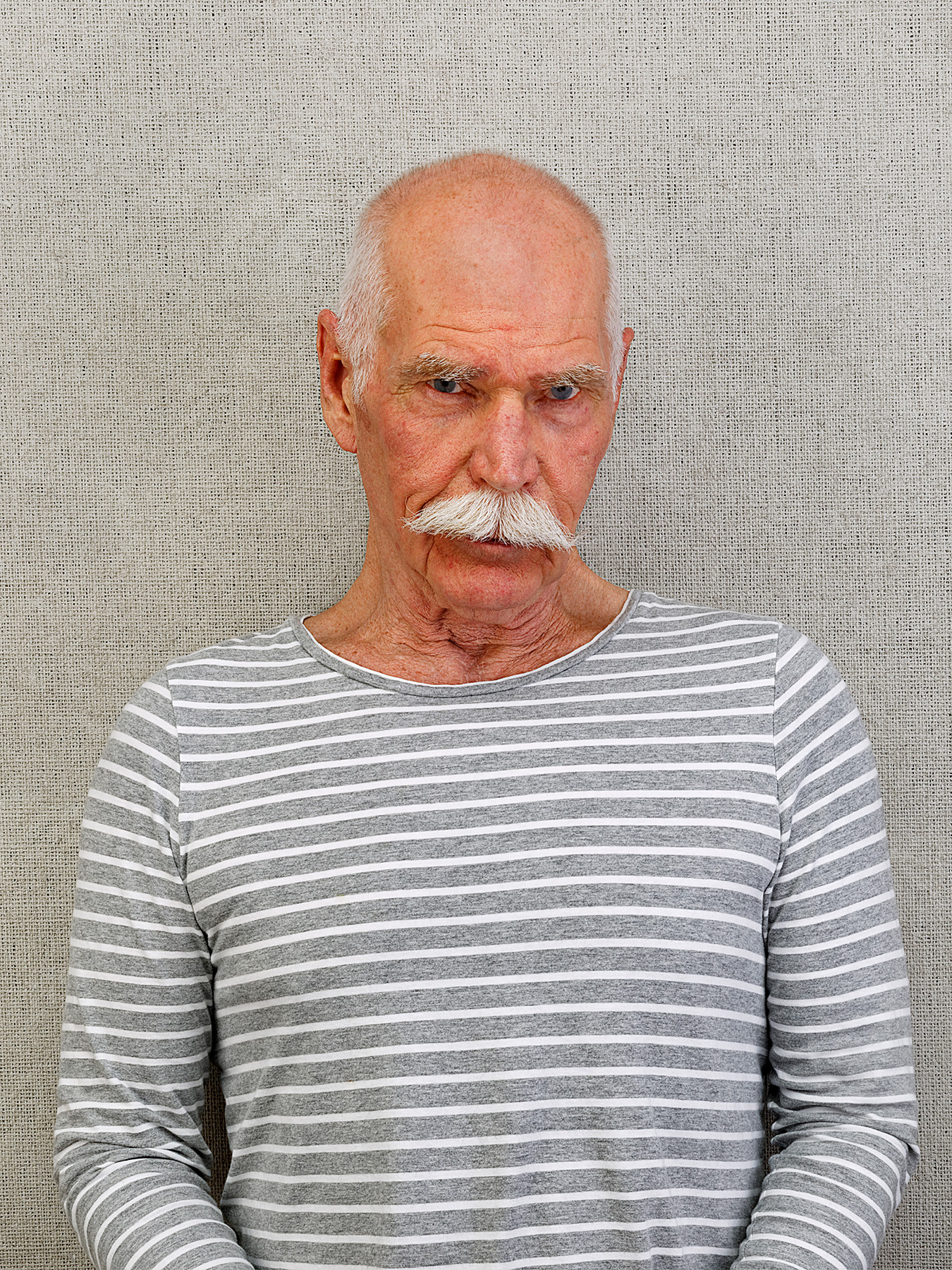

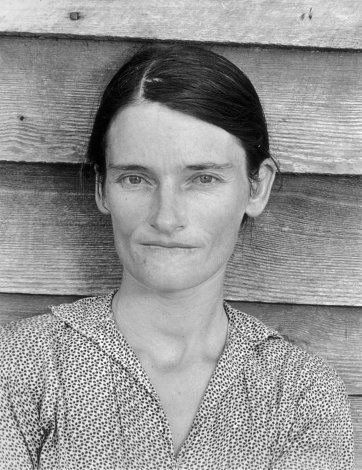

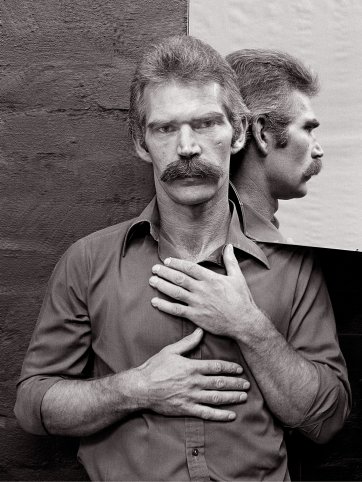

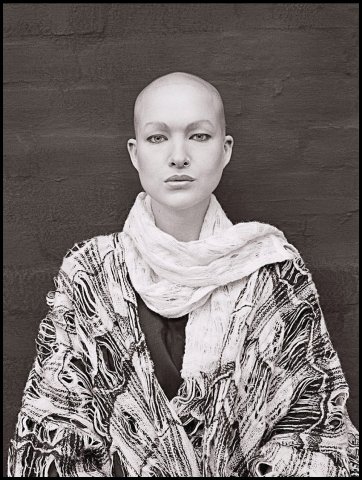

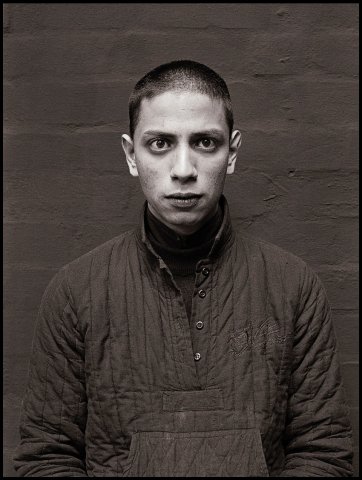

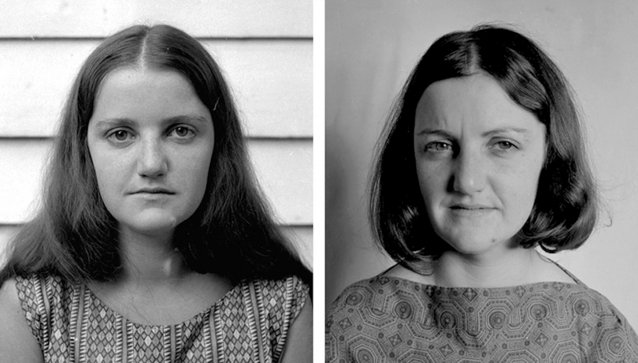

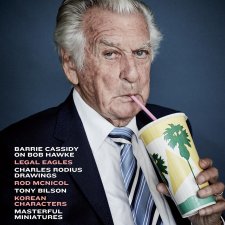

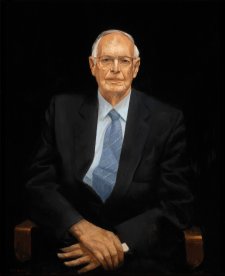

When you look at a Rod McNicol portrait, there is nowhere to hide. The piercing immediacy of the subject’s gaze places the viewer in a somewhat disconcerting space, raising the question, ‘who is observing who?’ The discomfort might subside as the viewer is drawn further ‘into the sitter’s sentience’, gleaning that the fixed gaze is an existential concern – that it’s a meditation on simply being. Stark to the lay eye, McNicol’s simplified portraits are laden with historical references, and – as I discover whilst chatting with him in the Fitzroy studio he’s lived and worked in for four decades – there are layers beyond the concept of sentience to which the photographer refers in his portraiture. There is time and patience; there is even a certain sufferance.

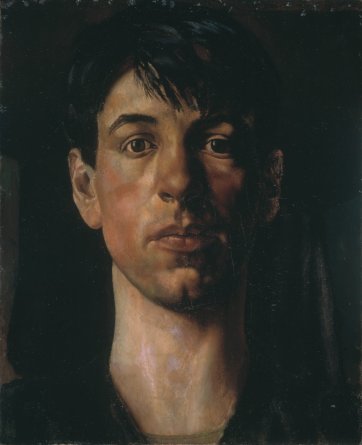

McNicol’s sitters are stripped of all context, exposed in a process the artist describes as ‘ruthless but tender and gentle’. In their very fierceness, his portraits reflect the precision of the purist behind the lens. Set against a dark background – with a straight-backed kitchen chair to restrict the posture, and every detail evenly lit via clerestories above – his sitters evoke, as McNicol describes, ‘the existential trace of time and mortality’. With the reference to mortality, Rod taps into philosopher Roland Barthes’ ‘eidolon’: the phantom contained within the image that actively transforms and regenerates the static figure into the imagined. And it is this haunting presence – the spectre within the image – that has occupied McNicol’s entire oeuvre, from the 1970s through to the present day.

Born in 1946 in Melbourne, McNicol would move to France in late 1968, where he was exposed to the progressive, heady ideals of a Paris transformed by the nationwide civil unrest of that year. Over the best part of five years in the French capital, McNicol associated with artists, writers and actors, occasionally participating in café theatre performances, and coming under the influence of European theatre collectives. This included the likes of revolutionary practitioner Jerzy Grotowski, who called for a ‘Poor Theatre’, an experimental approach where the theatre is stripped of all its superfluous elements, the actors making minimal use of set, costumes, props, and make-up. Grotowski’s purity of approach, which emphasised ‘the actor-spectator relationship of perceptual, direct, “live” communion’, would be an influence on McNicol’s future photographic practice.

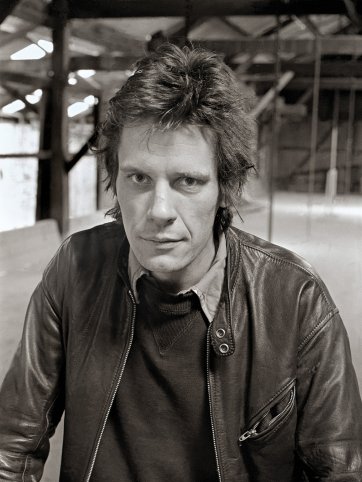

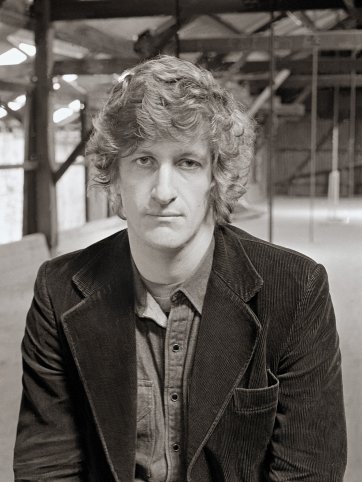

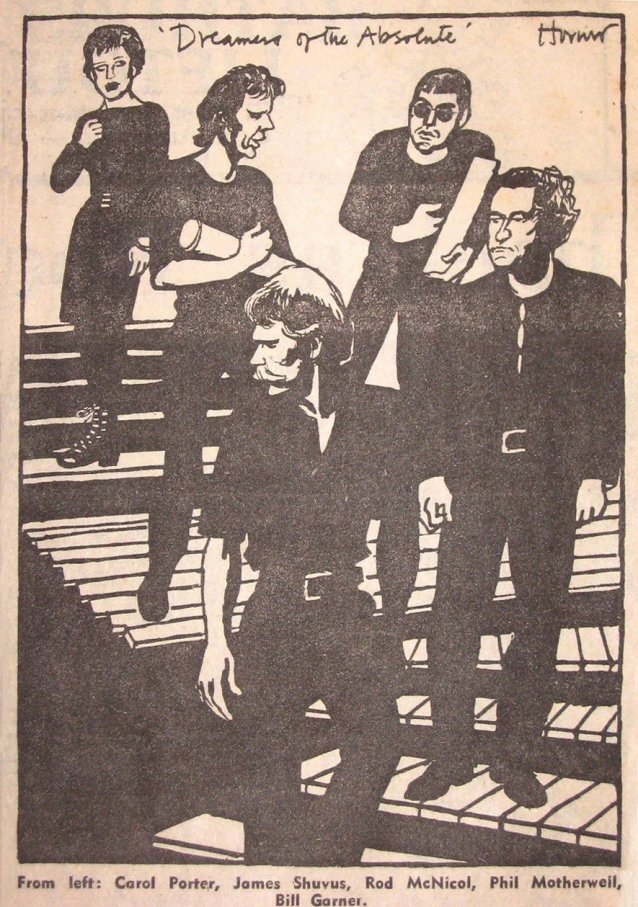

McNicol returned to Melbourne in 1973, and enrolled for a semester at Prahran Technical College’s department of photography the following year. Under the tutelage of preeminent photographic portraitist Athol Shmith, he was drawn to ‘straight’ portraiture, and the directness of the fatalist stare characteristic of nineteenth century photography (a product of the long exposure times of the period). As well as taking up the camera, McNicol resumed his interest in the theatre, joining the Australian Performing Group at The Pram Factory, a progressive theatre company in Carlton. There he found a like mind in playwright and actor Phil Motherwell, along with others interested in challenging and subverting artistic conventions.