When Stephen first went to the Victorian bar in 1952 he shared tiny chambers with two other barristers. One of them, Ivor Greenwood, had been Owen Dixon’s associate; twenty years later, as federal attorney general, he was to invite Stephen onto the High Court. The other was Edward ‘Ted’ Woodward. In the preface to Woodward’s autobiography, One Brief Interval, Stephen wrote that he’d known him for more than 50 years, as ‘barrister, judge, then in his more sinister role as head of ASIO, and subsequently as benign university chancellor’.

Like Ninian Stephen, Ted Woodward received an unexpected phone call. His was from Gough Whitlam, on 20 September 1975, which happened to be Woodward’s 25th wedding anniversary. While he joshed Whitlam about ringing to offer congratulations, he really ‘knew’ that Whitlam was calling to talk over the possibility of integrating Aboriginal laws and customs into Australia’s existing legal system. In fact, Whitlam had rung to invite Woodward to become head of ASIO. Lois Woodward was fearful; but his children – the Woodwards had seven – encouraged him to take the job. They wouldn’t have to move; until the mid-1980s the ASIO headquarters, like the High Court, were in Melbourne.

From boyhood, Sir Edward Woodward ac obe om wanted to be prime minister. He studied at the University of Melbourne in the late 1940s, and was admitted to the bar in 1951. In 1957, just as he might have entered politics, his father became Governor of New South Wales. Woodward junior, loath to cause embarrassment, shelved his plans. Remarkably for a man who ended up getting one of the last of the Imperial knighthoods – at age 52 – he claims he only twice applied for a position: first, to be promoted in the Citizen’s Military Force (the reserve army), for which he had to undertake an advancement course; and secondly, to become a Queen’s Counsel, which he was appointed in 1965. All Woodward’s other jobs came to him – and, he conceded, he got some ‘pretty good offers’.

Woodward had no more interest than most people of his time in Aboriginal land rights until 1968, when he was briefed by a small Melbourne solicitors’ firm to appear for the Yirrkala people in the Gove Land Rights Case, Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd and Commonwealth of Australia. Subsequently, Gough Whitlam invited him to head a royal commission into land rights in the Northern Territory. Recommendations of the Woodward Royal Commission of 1973-1974 laid the foundations for Northern Territory land rights legislation enacted by the Fraser government in 1976. Later, Woodward chaired the Aboriginal Justice Committee.

Woodward was head of ASIO in between two royal commissions into the organisation: the Hope Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security in 1974-1977, and its second iteration in 1983. For much of ASIO’s history, during which very close relationships with the CIA and MI5 were cultivated, its focus was on Soviet spies and communist front organisations. Some lawful leftists, both committed and occasional, felt persecuted. Labor minister Tom Uren claimed in 1979 that his phone had been tapped by ASIO for more than fifteen years, and Clyde Cameron believed he was under surveillance. Notoriously, Labor attorney general Lionel Murphy suspected ASIO of suppressing information on a murderous right-wing concern, the Croatian separatist group Ustaša. On 16 March 1973, in hours of darkness, the Commonwealth Police raided ASIO’s regional office in Canberra. They ransacked the Melbourne office the following morning – at two hours’ notice, as it turned out, because Murphy was delayed at Canberra Airport – but found no proof that ASIO had withheld information on the group at all. In due course, ASIO was mocked by the left for their lack of material on Ustaša. Interesting ulterior motives for the raids have been proposed ever since.

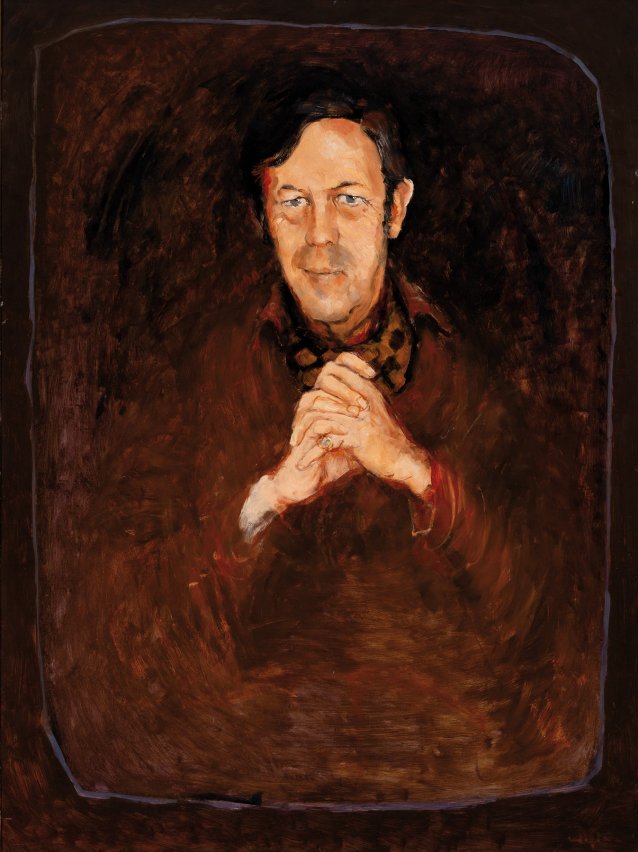

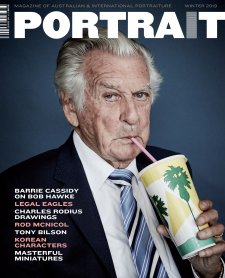

In Woodward’s absorbing, at times devastatingly intimate autobiography, the cover of which features a detail of the Pugh portrait, Woodward describes how it fell to him to rebuild ASIO in a time of unprecedented public interest in it. Inevitably, this meant restructuring, and introducing the ‘new accountability’ required by the evolving public service. He lamented the ‘almost complete absence of university graduates among the intelligence officers, and the complete failure to recruit women to such positions’, and stated he found some officers defective in intelligence or character. John Miller, a former intelligence officer, has a very different view of the skillset of the pre-Woodward staff. He writes that while most of them thought Woodward a fair and decent man, he made it ‘abundantly clear that serving ASIO officers were essentially a pack of outlaws ... the rank and file were regularly reminded of their previous indiscretions and the potential for their redeployment elsewhere.’ Adding to everyone’s stress was the forthcoming relocation of the agency to Canberra. In general, Woodward presided over a hopeful period for recruits to ASIO, and a miserable one for long-term employees.

A bomb exploded outside the Sydney Hilton, venue for the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, in February 1978. The Hilton bombing – masterminded, it’s generally agreed, by a violent faction of an Indian cult called Ananda Marga – constituted Australia’s initiation into international terrorism. Malcolm Fraser felt more nervous about his own safety, and that of his family, than any previous prime minister, and his personal tensions informed policy. Meanwhile, some alleged that ASIO agents had planted the Hilton bomb themselves to underscore the organisation’s relevance. ASIO’s obsession with communism began to wane in this period. Anyway, Woodward jested that he had a working knowledge of Soviet activity because the guest bedroom in his mother’s tenth-floor flat in Woollahra looked straight down on electronic gadgetry on the roof of the adjoining Russian consulate. When he left ASIO, his staff gave him a pair of binoculars.

Woodward doubtless gained a huge body of general knowledge about Australia through his participation in seventeen royal commissions, of which he led four, including the 1982 Royal Commission into the Australian Meat Industry (in which Kenneth Hayne was an assisting barrister). Apart from that, he was a justice of the Federal Court of Australia from 1977 to 1990. Ninian Stephen had already accepted the position of chancellor of the University of Melbourne in late 1989 when he was named ambassador for the environment. From 1990 to 2001, Woodward held the keys to the chancellor’s office instead. Amongst his governance activities, which included sustained involvement in mental health initiatives, he was chairman of the Victorian Dried Fruits Board.

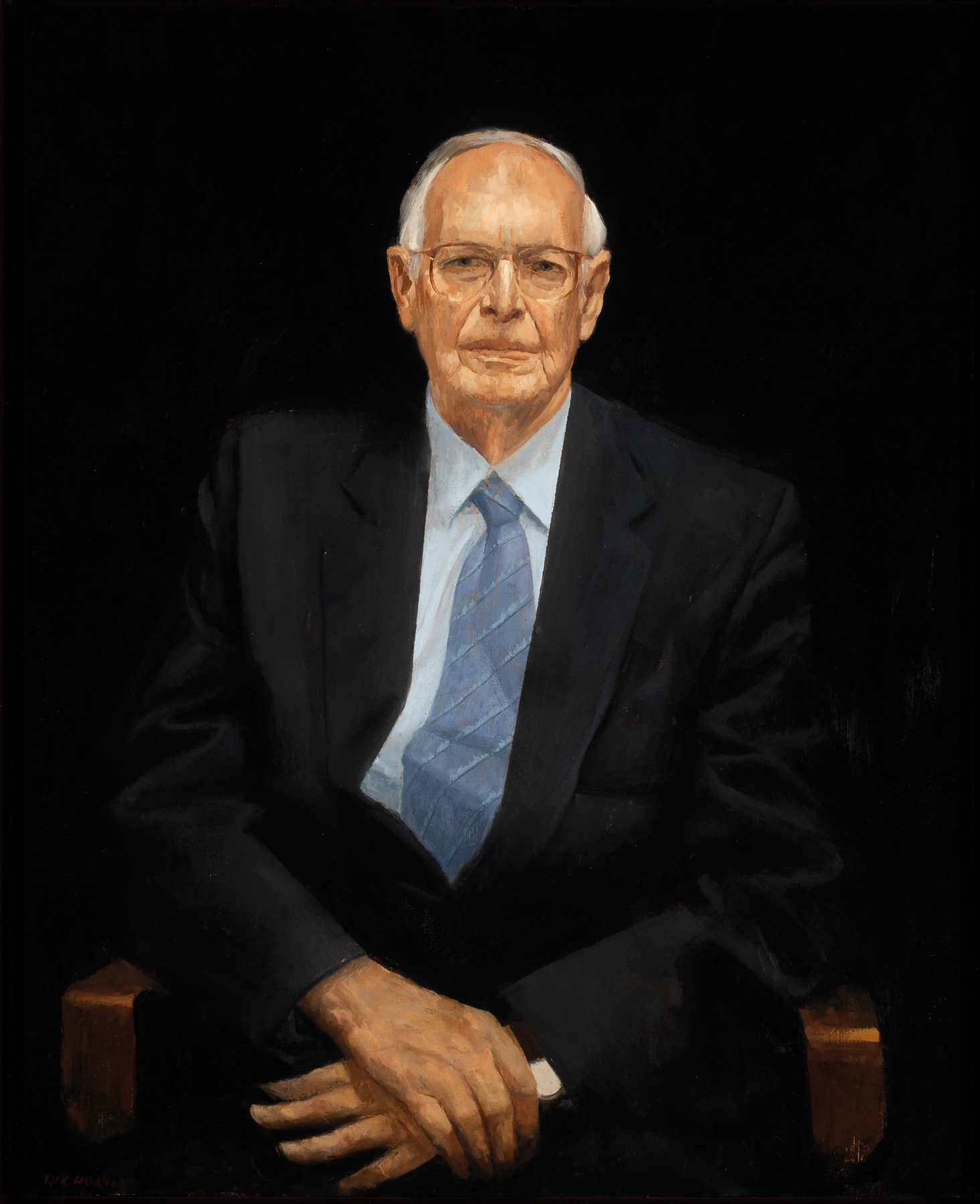

Figures in portraits by Clifton Pugh often feature steeply sloping shoulders, the lines of which extend into the suggestion of an egg shape within the rectangular composition. Typically, the face and hands appear more attentively rendered than other elements of the work, which are frequently gestural; there’s often an element of pattern somewhere. In conversation recently, Rick Amor observed that Pugh tended to make his sitters look wistful, no matter how forceful their personalities. The portrait of Woodward comprises all these elements and tendencies.

In her memoir of the period of her life she spent with the artist, Judith Pugh tells of Clifton Pugh’s meeting with Edward Woodward. The Pughs had tasked friends with introducing them to interesting people. Betty and Ray Marginson – the latter long-time vice-principal of the University of Melbourne and founder of the Potter Gallery – invited them for dinner with Ted and Lois Woodward. Judith had heard that Gough Whitlam had recently asked a Ted Woodward to become head of ASIO; but the couple they met at the Marginsons’ were so intelligent, pleasant and forthright that Judith initially thought they must have been matched with a different Ted Woodward. She became increasingly uneasy as Pugh, an inveterate leftie, alternately sentimental and pugnacious, made one of his characteristic generalisations, and the judge, unrelenting, backed him into a corner over it. Thanks to Woodward’s geniality, general laughter ensued, but I recognised the table tactic, with a wince. You get that when you have QCs to dine.