As a National Portrait Gallery curator, one quickly learns the rule of thumb that the proof of a good portrait often lies in the strength of the contract between artist and sitter: a conscious effort on the part of the former to reveal something of their subject, and on that of the latter to reveal something of themselves. The equation is less straightforward, however, when, in using portraits to present a nuanced and accurate narrative of nineteenth-century Australian life, one has recourse only to images made in a context of inequality and that, at first glance, bear a distinct, colonial signature. Objects such as blankets, for instance, often figure in nineteenth-century Australian representations of Indigenous sitters. Though seemingly benign, blankets can also be read as symbols of the unseen but omnipresent paternalistic power which assumed that Aboriginal peoples needed ‘civilising’. These supposed gifts were recorded in what are now known as blanket lists – documents that detailed people’s names, ages, and ‘District of Usual Resort’, but that functioned also as a means by which the authorities kept tabs on individuals’ activities. The appearance in portraits of gorgets or breastplates – usually inscribed with the spurious designations of ‘King’, ‘Chief’ or ‘Queen’ – similarly signify the presence of European newcomers and the processes by which they sought to curtail traditions and connections to country. Like the annual distribution of blankets, the issuing of breastplates was introduced to New South Wales by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who would have become au fait with the practice while serving in North America. There, it had been British and French custom to gift engraved gorgets to First Nations allies, in the same way that Cook, or Lewis and Clark, handed out medals to the custodians of ‘discovered’ territories. The historian Inga Clendinnen once described these objects as part of ‘the standard inventory of the smiling face of imperialism’, for which reason their presence in portraits can have unsettling, negative and derogatory connotations.

Expect the unexpected

by Joanna Gilmour, 5 August 2019

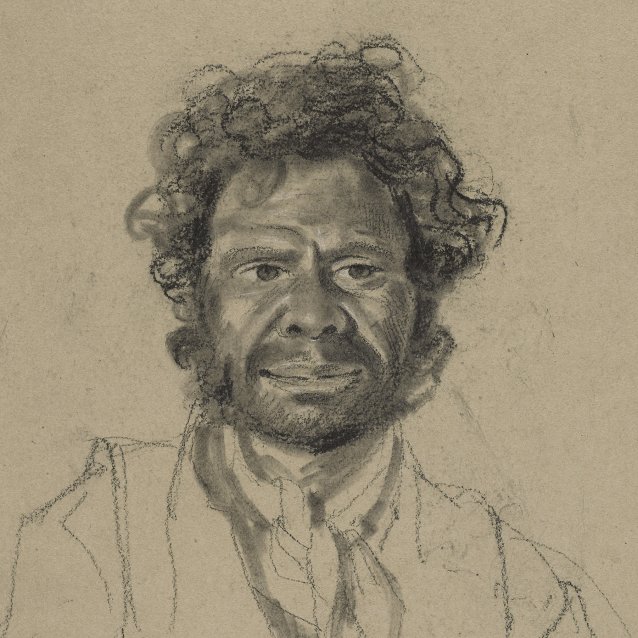

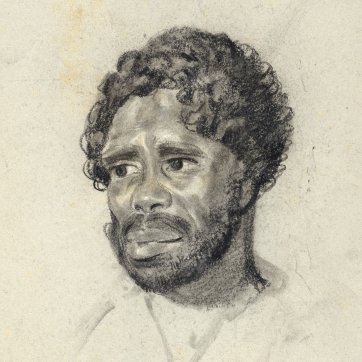

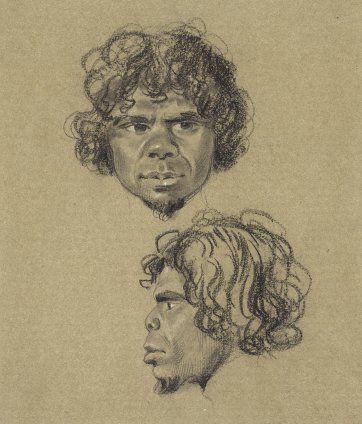

Take some of the portraits made in Sydney by Charles Rodius (1802–1860). An exemplar of the ‘accidental’ nature of Australian art, Rodius is one of several expert draughtsmen who would likely have slipped from art historical notice completely were it not for the misdemeanours that saw them exiled to the colonies. In Rodius’ case it was the theft of a reticule outside the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden in 1829, for which offence he was banished to New South Wales for seven years. Though his story was lamentably in line with those of other chaps who erred having fallen on hard times, Rodius was perversely fortunate in being possessed of a skill for which there was demand in Sydney, and that enabled him to turn his situation to advantage. As an employee of the public works department and the colonial architect, for example, he had access to a lithographic press and within three months of arriving in Sydney he’d issued a print of the Guringai diplomat and navigator Bungaree (c. 1775–1830). According to the Sydney Gazette it was ‘executed in the most finished style of the art, and is, moreover, as accurate and striking a likeness as we ever saw’. Rodius also made useful social connections through his work as a drawing teacher to high-ranking civilians and their families. He subsequently completed commissions for the free settler and ex-convict classes throughout the settlement, such that you can draw a map of Sydney using Rodius’ portraits as compass points. On the north side of the harbour there were sitters such as Bungaree on his land at Middle Head; or the African American ex-convict mariner Billy Blue, who operated ferries between Warrane (Sydney Cove) and the isthmus on the north shore known as Blues Point. In the south Rodius’ clients included entrepreneur and arts patron Alexander Brodie Spark, whose property portfolio included the picturesque villa Tempe House; and heading west there were clients like the Blaxland family, the occupants of the Newington estate on the Parramatta River. The present-day eastern suburbs and city were also peppered with his subjects: among them Car–oo or Kaaroo, known to the Europeans as Gooseberry; her kinsman Warrah Warrah or William Worrall, who lived beside the South Head Road at Rose Bay; and members of the community of people who often camped above Woolloomooloo Bay in the Domain.

Historian Paul Irish has described the Domain and other harbourside campsites as ‘staging posts for forays into Sydney’ by locals like Gooseberry, and those visiting from the Shoalhaven River, Broken Bay and further afield who favoured the Domain for its easy access to Circular Quay and the town with its various economic and strategic opportunities. For his part, Rodius – like any artist trying to make a go of it in a narrow market – was alert to the opportunities presented by portraits of these sitters, and during the 1830s made drawings of several individuals who were residing temporarily in the Domain. Eighteen of these drawings, including portraits of visiting Māori dignitaries, were acquired by the British Museum in 1840.

Masterfully rendered in pencil and chalk, their subjects include the Dharawal men Nunberri and Sangrado; Cullabaa (or Culaba), who Rodius described as being from the ‘Five Islands Tribe’ (near present-day Wollongong) and his wife, Punch; and Monowara, from Jervis Bay. The women wear scarves over their hair, blankets or capes around their shoulders; several of the men are in shirts. Rodius depicted Monowara with a breastplate inscribed ‘King Jack Waterman’, while the profile drawing of Nunberri includes a separate sketch of the ‘copper token’ by which he was designated ‘Chief of the Nunnerahs’. Rodius repurposed other drawings of some of the same sitters for six lithographs published in 1834, which he sold at one guinea for the set. The price was declared by one report to be ‘very moderate’; furthermore, ‘sets of these drawings would prove very acceptable presents to friends in England’.

This is not to say, however, that their subjects were mere curiosities. Though first impressions of the drawings might indicate otherwise, to see them up close as I once did on a gloomy London winter day is not only to encounter tangible evidence of dispossession and injustice, but to invite a way of looking that casts these images as signs, to quote Irish again, of ‘people shaping their destinies in the face of devastation.’ Monowara and Nunberri, for example, were not ciphers, nor nameless ‘specimens’ for Rodius to sketch, but men whose knowledge and skills were valued by influential colonisers – and who utilised these contacts to achieve their own ends. Just as blanket lists, with their cold, dispassionate facts, are now considered valuable resources, perhaps even touchstones, for the descendants and communities of the people recorded in them, Rodius’ portraits are proof of the resilience and continuing presence of Aboriginal peoples in Sydney at a time of intensified colonisation, and of the complexity and extent of cross-cultural transactions in the colonial era.

Related information

Portrait 63, Winter 2019

Magazine

Rod McNicol's method and motivation, 19th century Indigenous peoples, Barrie Cassidy on Bob Hawke, five generations of the Kang family from Korea and more.

Little women

Magazine article by Joanna Gilmour

Joanna Gilmour looks beyond the ivory face of select portrait miniatures to reveal their sitters’ true grit.

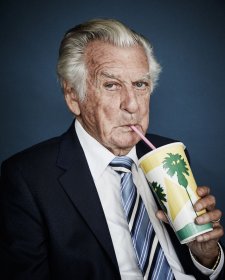

The intellectual larrikin

Magazine article by Barrie Cassidy

Barrie Cassidy pays textured tribute to the inimitable Bob Hawke.

![Portrait of Oltery[?] Chief of Otago, New Zealand, a heavily-tattooed Maori man in profile to right, 1834 Portrait of Oltery[?] Chief of Otago, New Zealand, a heavily-tattooed Maori man in profile to right, 1834](/files/8/e/8/9/i12578-th.jpg)

![Portrait of Qualla[?] from Otago, New Zealand, a tattooed Maori man in profile to left, with, lower left, a detail of the tattoo between his eyebrows, 1834-5 Portrait of Qualla[?] from Otago, New Zealand, a tattooed Maori man in profile to left, with, lower left, a detail of the tattoo between his eyebrows, 1834-5](/files/3/5/4/1/i12579-th.jpg)

![Two views, full face and in profile to left, of the head of Taekghi[?] from Kangango[?], a heavily tattooed Maori man, with a detail of the tattoo on his forehead, 1834-5 Two views, full face and in profile to left, of the head of Taekghi[?] from Kangango[?], a heavily tattooed Maori man, with a detail of the tattoo on his forehead, 1834-5](/files/9/1/5/c/i12580-th.jpg)