During the period known as ‘the Tensions’, from 1998 to 2003, Solomon Islanders had little to smile about.

The small Pacific nation once known as the ‘Happy Isles’ was engulfed in an internal ethnic struggle that descended over several years into all out conflict on the streets of the capital, Honiara. The growing political and economic instability, coupled with a lack of any plan for recovery, saw the country teetering on the brink of failed state status, with civil and economic collapse imminent. The Solomon Islands Government’s consequent request for external intervention was met with a decisive response from Australia, which led fifteen Pacific island countries, including tiny Niue, to form the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands – RAMSI – or Operation Helpem Fren, in July 2003. The mission’s outcomes are manifest: in 2017, after fourteen years of peacebuilding, full control of the country’s future was returned to the Solomon Islands Government and Royal Solomon Islands Police Force. Today, this young nation looks forward to its future with confidence and a sense of renewal.

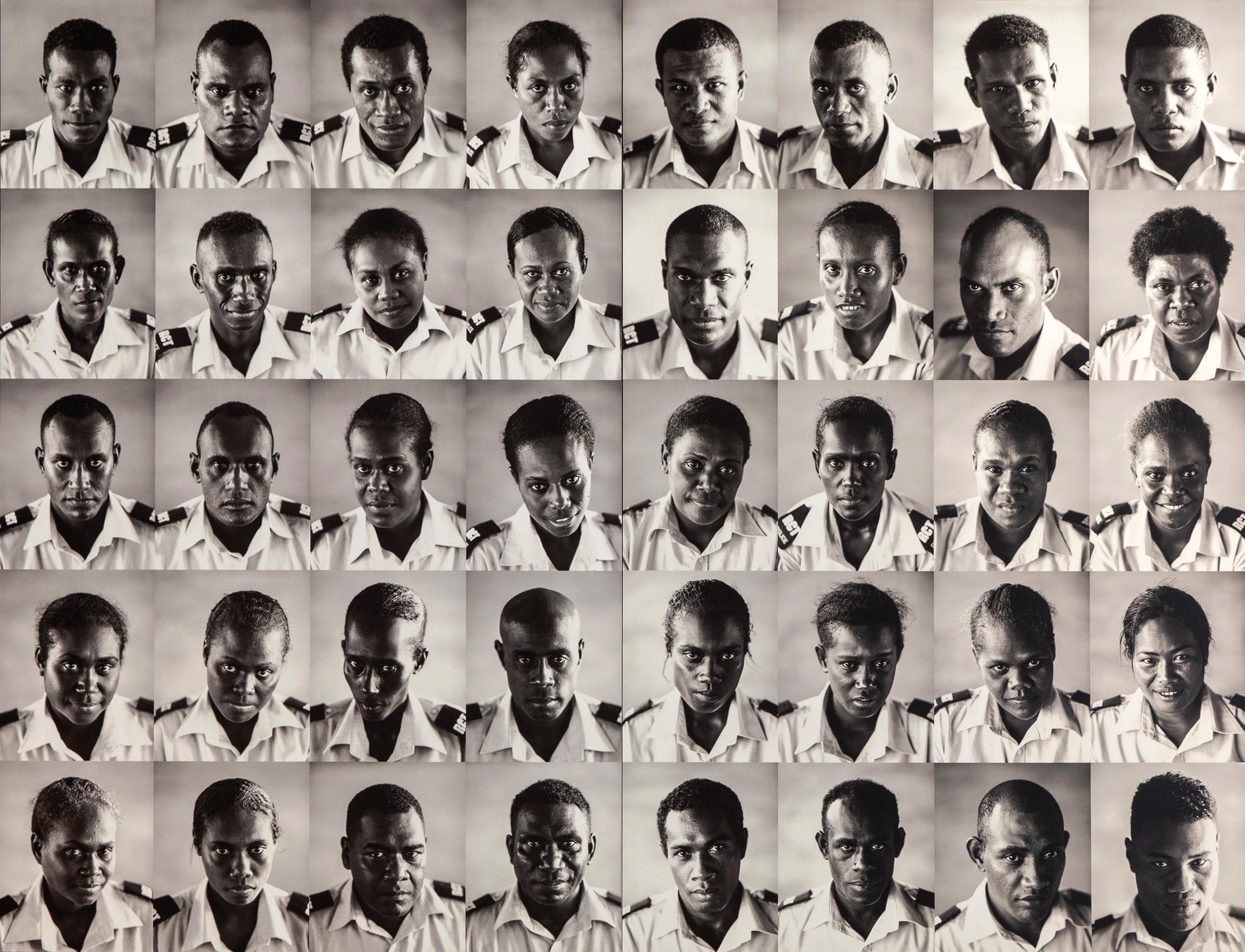

In 2017 the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade commissioned Sean Davey to photograph the drawdown of the mission, and to produce a series that revealed the state of the country at this pivotal moment in its history. The subsequent exhibition Next Generation: Solomon Islands After RAMSI captures aspects of daily life in Honiara, as well as the air of excitement and optimism that permeated the capital. Life on the streets had returned to normal, and indeed it is this normality that is so striking. These photographs could have been taken anywhere – they might have been from an Australian town – and yet the sum of the images, quotidian, poignant and joyful alike, constitutes the portrait of a nation emerging anew.

It is difficult to grasp just how far Solomon Islands has come since the Tensions began, when the small archipelago of islands in the Pacific made headlines for all the wrong reasons. Images of Honiara’s Chinatown ablaze, shops looted, gang violence, rioting, and boys running amok with stolen military-grade weapons filled news reports around the globe. The images were surreal, like excerpts from a Hollywood film, except the scenes were anything but staged and were occurring on Australia’s doorstep. Two hundred people lost their lives. It was utter chaos from any objective standpoint, but most shocking are the personal accounts of ordinary citizens who lived through this period, and the trauma it caused.

‘When they came I had to hide my children in the house. I take one of my sons and hide him under the bed, cover the bed. I take another girl and put her in the cupboard. Close the cupboard. And I take the baby, two years old, and I lay her on the bed. If they come they can kill her because she is just a baby. So I have to stand at the door and prepare to meet these men who is coming (sic). I don’t worry about me dying, but I worry about the children.’

(Village elder, Verahue, July 2017.)

Emotions from the Tensions are still raw; the trauma will take decades to heal. However, for most Solomon Islanders enough water has flowed under the bridge. RAMSI has given former foes the breathing space needed for peace to flourish, with the next generation seemingly willing to reconcile their differences and get on with life. Modernity facilitates a new focus – there is engagement with technology, fashion, social media, fitness, education, trends and language-learning. The country’s leaders, intelligentsia, entrepreneurs and investors are returning with their families from self-exile in the provinces, or lucrative work overseas. The next generation is confident, passionate; they know what they want. The country is on the cusp of big things.

Dr Shaune Lakin, Senior Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Australia, brought astute context to the Solomons commission at Next Generation’s opening night in Canberra: ‘How do you photograph this place [Honiara] when you don’t have the language of conflict to draw on anymore? Because we’re outside of this period of conflict, we’re in this period of peace … what does peace look like?’ It was a consideration that mirrored my own before the commission. What I feared most was a photographer looking for action or drama, as they wouldn’t find it – essentially, if it had been there, then RAMSI had failed. I needn’t have worried, as Sean ‘got it’; he had the brief and the experience, but most of all he cared. He cared about Solomon Islanders and took an interest in their stories, with this deployment another outing in his lifelong engagement with the Pacific. He had a real, uncontrived connection to the people. He also had an extensive back catalogue of street photography and informal portraiture to draw upon.

Sean is a photographer who creates his own luck by, in his words, being ‘present’. He gives his time freely and adapts to whatever may transpire, as well as carrying his trusty rangefinder wherever he goes. He notes, ‘it is about having your camera ready and opening yourself up to new opportunities and experiences’. A typically serendipitous exchange came about as Sean was heading out to photograph an official street parade to kick off the end of RAMSI celebrations. He left early that morning to walk across town to our rendezvous point. Proximity to the equator means stronger sunlight, so mornings were Sean’s ‘golden’ window of opportunity to shoot to his heart’s content. Roaming the streets along the way, he ran into the Belaga family.