The Rajah was your garden-variety convict ship in most respects. A 352-ton barque constructed in Whitby, it left England in early April 1841 and sailed into the Derwent River 105 days later, having lost only one member of its human cargo. According to the notes made by its surgeon-superintendent Dr James Donovan, over 80 percent of the convicts on board had behaved in an acceptably quiet and obedient fashion, and some of them he even declared to have been ‘very good’. Along with official notification that the colony’s attorney-general and solicitor-general had both been sacked, the Rajah brought with it from London news of Queen Victoria’s pregnancy (Her Majesty’s ‘fair proportion was a matter of much public rejoicing’, apparently), as well as ‘nine varieties of the camellia, four of the magnolia, three azaleas, arbutus, myrtles, &c., &c.’, all imported for propagation by members of the Launceston Horticultural Society by a Mr Davies – specifically, the Reverend Robert Rowland Davies of Longford, who was also returning to Van Diemen’s Land with a £1000 loan from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. Most significantly, among the numerous items disgorged from the Rajah’s hold was a patchwork quilt – or, technically speaking, an unlined patchwork coverlet – that had been stitched by some of the 180 transportees on board under the supervision of the ship’s matron, Kezia Hayter. It was in this that the Rajah deviated from the norm. Whereas, since the early 1820s, it had been usual to attempt to instill ‘order, sobriety and industry’ in female convicts by supplying them with sewing materials on embarkation, it is unusual for the results to have survived. Quilts and other items could be sold en route, for instance, or put to use on arrival in the colony, stacking the odds against longevity of useful life and preservation. The coverlet pieced together by the Rajah’s women, in contrast, was constructed with posterity in mind, an enduring proof of beliefs about the redemptive power of work, and of the grace and dignity that might be fashioned from graceless, undignified circumstances. It follows that the ‘Rajah quilt’, as it’s now known, has become something of a talisman. Art historians and decorative arts boffins are in thrall to its design, components and construction; social historians salivate over its eloquence as an artefact; and the numerous descendants of the women involved in its creation revere the quilt as a tangible, palpable link to their ‘tainted’ convict forbears.

Ruffles on the Rajah, 2018 by Bern Emmerichs

Material culture

by Joanna Gilmour, 2 October 2018

It can be easy to forget that Van Diemen’s Land – a netherworld by reputation as well as geography – was hardly peripheral when it came to theorising on prison reform, and that the colony was something of a testing ground for what were then rather progressive concepts about crime, its causes and consequences. The Rajah quilt, to begin with, evidences the ideas and far-flung influence of the Quaker reformer and philanthropist Elizabeth Fry (1780–1845) who, following a number of exceedingly discomfiting visits to Newgate Prison, founded the British Ladies’ Society for Promoting the Reformation of Female Prisoners in 1817. As explained by the Society’s 1839 manifesto, when Fry first visited Newgate in 1813 she found that around three hundred women inmates and their children were confined in two wards where they were supervised (God forbid) by a male warder and his son. Beer and ‘other indulgences’ were readily available, ‘there was no bedding whatever’, and the women’s clothing was ‘shockingly insufficient’. More egregiously, the inmates had sod all to do with their time. This was deemed ‘a most serious evil, and a pre-disposing cause of every vice’, enabling inmates to be schooled in ‘the mode of committing more extensive and injurious crimes’ and not in the encouragement of them to repentance. ‘Many who entered Newgate comparatively innocent, left it depraved and profligate’, Fry believed. Outraged on both the spiritual and temporal fronts, she and the members of the Society thereafter focused on improving the welfare of women prisoners, establishing a school for Newgate’s children and negotiating for the implementation of basic reforms such as the appointment of matrons and the classification of inmates, as well as the introduction of weekly Bible readings and opportunities for productive, paid employment. Historians Trudy Cowley and Dianne Snowden, whose 2013 book Patchwork Prisoners is the authoritative account of the Rajah women, describe Fry’s prison reform philosophy as being grounded in the ‘twin principles of useful labour and religious instruction’, rendering the prison less a machine to grind rogues honest and more a crucible for the incubation of ‘habits of virtue and industry’. The Society later formed the Convict Ship Committee to oversee the application of these principles at sea, and from the early 1820s, as related by The Memoirs of Mrs Elizabeth Fry (1847), each woman transported on a ship from south-east England was supplied with a Bible, an apron and cap, as well as a handiwork kit that included scissors; a thimble; needles; pins; wool; balls of cotton in a few different colours; ‘one pair of spectacles, when required’; and ‘two pounds of patch-work pieces’. By 1847, to quote the same source, ‘one hundred and six ships, containing about twelve thousand female convicts, are reported as having been visited by the Ladies of this Society’ and the Convict Ship Committee was able to ‘indulge a hope that the instruction and moral discipline, now generally adopted during the voyage, are the means of preventing much evil, and of promoting the moral and religious improvement of those who are suffering the penalty of their crimes’.

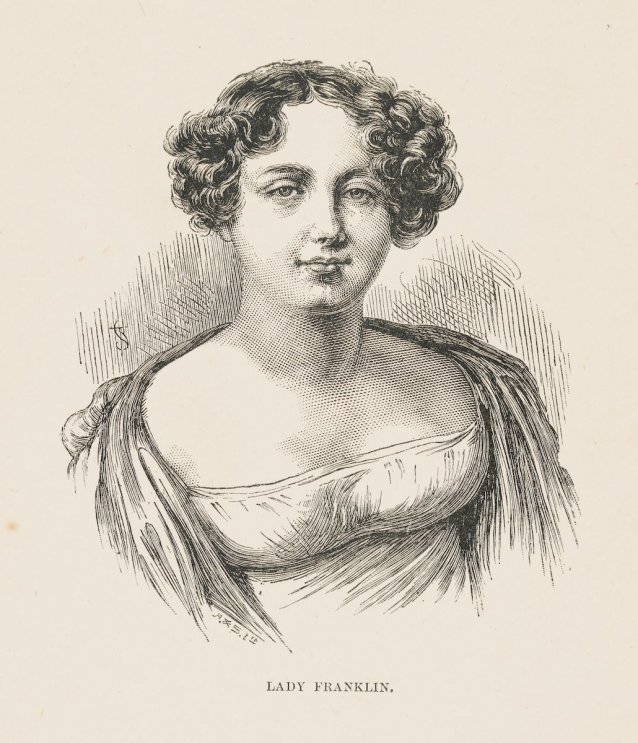

From the outset, it seems, the Rajah was considered an exemplar of Fry’s philosophy, as when it docked in Hobart in July 1841 it was declared that its convicts were ‘of much better character than usual, … doubtless in a great degree the result of the indefatigable care which appears to have been exercised both with reference to their morality and physical comfort’. Reverend Davies, one of the Rajah’s few paying passengers, was said to have assembled the ship’s entire company ‘on the evening of each passing day, for the purpose of prayer and praise’, and the convicts were generally agreed to have been aided by the superintendence of Hayter, ‘a female of superior attainments, who had previously been an officer at the General Penitentiary, and who obtained a free passage in the Rajah with the understanding that she should devote her time during the voyage, to the improvement of the convicts’. In addition to this blessing, it was anticipated that the quilt would earn the imprimatur of the then first lady of Van Diemen’s Land, the redoubtable Jane Franklin (1792–1875), who corresponded with Fry and who, for a time, made the management of women convicts one of her various reformist projects. This, in fact, was one of Lady Franklin’s more acceptable pursuits, noting that she is typically distinguished from the majority of colonial vice-regal spouses for her involvement in matters considered beyond the ken of unimpeachably ladylike ladies. In 1832, a few years before her husband’s appointment as the colony’s lieutenant-governor, Franklin had begun to follow Fry’s work with interest and as a consequence came to Hobart having undertaken to furnish Fry with particulars on the condition of Van Diemen’s Land’s female convicts. Initially, as Franklin biographer Alison Alexander has explained, Jane did very little, seeing the convicts themselves as ‘impudent creatures’ and the ‘whole system of female transportation … so faulty and vicious, that to attempt to deal with the women who are the subjects of it, seems [a] waste of time and labour’. Philosophically, therefore, Franklin was at odds with Fry, believing convicts needed to be punished rather than preached at.

The Rajah is said to have revived her interest in the issue. A few days after the vessel’s arrival, she noted in her diary that she and her husband ‘went on board Rajah’, and that, after Sir John had delivered a ‘long and good address’, the quilt was displayed for the assembled dignitaries. Though Lady Franklin would appear to have been largely unmoved – expending more words, for example, in recording the talk of Hayter’s betrothal to Charles Ferguson, the ship’s captain – her diary entry for the day allowed for the merest mention of the quilt’s stitched inscription. This was the way by which the makers expressed their gratitude to the ‘Ladies of the Convict Ship Committee … for their welfare while in England and during their passage’, while the quilt itself furnished ‘a proof that they have not neglected the Ladies’ kind admonitions of being industrious’. Jane Franklin was sufficiently inspired to form a ladies’ committee of her own along Fry’s lines, and was impressed enough with Hayter to offer her accommodation at Government House and a job as a part-time tutor to her step-daughter and as a consultant, of sorts, on the matter of the Cascades Female Factory and its purportedly impudent occupants. Hayter, however, declined the job, discomposed by Lady Franklin’s eccentricities and dearth of evangelical zeal. ‘What a grievous thing it is her heart is not under correct influences’, she wrote. Regardless, Hayter involved herself with work at the Cascades until leaving Hobart in April 1842, when she became the governess at Brickendon Estate, a property belonging to one branch of the prominent, landowning Archer family at Longford.

The quilt, meanwhile, disappeared. Its story between the time it was shown to Jane Franklin in Hobart in July 1841 and its appearance in the collection of a family in Scotland a century later remains unknown. As the conservators who are its lucky custodians have explained, the quilt itself tells us – from the flawless condition of the fabric dyes, for example, or the bloodstains from pricked fingers that were never cleaned up – that it was hardly, if ever, put to use, was never washed, nor in all likelihood ever exposed to sunlight. It has been suggested that the quilt might have returned to Britain with Hayter on one of her several trips ‘Home’, although she largely remained in Australia following her marriage to Ferguson in Launceston in 1843, residing in Sydney, Hobart and Melbourne before settling in her dotage in Adelaide. Others have proposed it was presented to Fry at some point, but there’s no traceable link between her or the Rajah and the quilt’s twentieth century Scottish owners, from whom the National Gallery of Australia acquired the quilt in 1989.

And another idea, although there’s nothing in her voluminous writings to indicate it, is that Lady Franklin kept the quilt and still had it with her when she left Australia, departing from Geelong in January 1844 on the Rajah. ‘January 10 – Rajah, barque, Ferguson master, for London; Passengers, Sir John, lady, and Misses Franklin and two servants, Mrs Ferguson’, as the Geelong Advertiser’s shipping news noted. Yet whether or not the quilt will ever give up its secrets is perhaps immaterial. Just as its fabrics and construction constitute, as curator Robert Bell has said, ‘a cross-section of the contemporary textile technology of the period, its patterns, printing techniques and design influences’, the quilt is also akin to a sampler, an intricate and decorative (if sometimes unschooled) demonstration of the complex of stories inadvertently stitched into its 2815 pieces. The subsequent histories of many of the Rajah convicts, as Cowley and Snowden’s research has shown, thereby supply something of a map to the composition of colonial Australian society and the actual, mostly irreproachable, consequences of convict transportation on the colony’s population.

Consider the example of Elizabeth Archer (c. 1820–1884), who was 21 years old when she was loaded onto the Rajah for removal to Hobart. A native of Yorkshire, Elizabeth had already served several gaol sentences –for drunkenness, and being ‘lewd and disorderly’ – before she and a woman named Ann Wright were jointly tried in Bradford in July 1840 for stealing money.

According to a newspaper report of one of her court appearances, Archer was from a troublesome ‘batch of prostitutes’, while the Bradford Observer’s article about her trial with Wright stated that they had both ‘been long on the pavé’ – so long, in fact, that they had no chance of mitigating their punishment by pleading guilty. Reading between the lines, one can assume that their victim in this case – the unfortunately, if somewhat appositely-named Joseph Muff – was a feckless john whose purse was purloined by one half of the pair while he availed himself of the charms of the other. With their ‘long list of previous imprisonments’, the court deemed that another gaol term was pointless and decided instead that they be ‘each transported beyond the sea for the term of Ten Years’. The Observer reported that Archer ‘immediately clapped her hands’ on being sentenced, while Wright is said to have addressed one prosecution witness ‘in language too gross for publication’. Archer’s experience of the ensuing time in prison, the ministrations of the Convict Ship Committee and the voyage itself, if her convict record is an accurate guide, had little reformative effect. In Hobart she was promptly assigned to the service of Dr Henry Brock, formerly a surgeon-superintendent on a number of convict voyages, but soon added to her catalogue of misdemeanours.

On two separate occasions in December 1841 she was charged with ‘disobedience of orders’, and by January 1842 she had served a pair of ten-day stints of solitary confinement at ‘that receptacle of wickedness’, the Cascades Factory. A year later she is recorded as being assigned to an employer in Oatlands where, in April 1844, she appeared before the magistrate charged with ‘insolence to her mistress Mrs Cahill, and refusing to remain in her service’. For this, Elizabeth was given a month with hard labour at the Female Factory in Launceston. Another stint at the Cascades (again for insolence and refusing to work) followed in June 1844, but she was nevertheless granted a ticket of leave that December and within a year of receiving it had married. Her husband, William John Read (or John William, depending on the source), was also a convict. He’d been transported for life for theft in 1837. Her not insubstantial list of colonial transgressions notwithstanding, Elizabeth was recommended for a conditional pardon, granted in 1849. The following year she and her husband joined the vast cohort of Tasmanians, ex-convict and not, who decamped for Port Phillip and the opportunities it presented for remaking oneself and for trading ignominious, forgettable beginnings for gentility and down-home respectability.

Elizabeth’s portrait, an as-yet unattributed watercolour held in a private Sydney collection until 2017, indicates that she succeeded in this. The work is a true delight for those of us whose fate it is to be preoccupied with colonial Australian portraiture, but whose proclivities are often thwarted when a work is discovered to be so displaced from its history that identifying the sitter, never mind the artist, is next to impossible. In Elizabeth’s case there are inscriptions on the reverse – maddeningly succinct shards of information that, even with their misspellings (‘Elizabeth. Born 1821. Married Jhon Wm Reid Oatlands 1845’), are simultaneously meaty enough to tempt further investigation and that, better still, prove to be satisfyingly verifiable by archives and primary sources.

As is so for The Rajah quilt, Elizabeth’s portrait alludes to a broader, intricate historical realm: demographics, patterns of settlement, the convict diaspora and colonial social mobility. In this the work is an elegant distillation of the conditions which facilitated the predominance of portraiture in the output of colonial Australian artists, for whom increasing numbers of free settlers and the remade emancipist class constituted a considerable market from the 1830s onwards. The best collections of nineteenth century Australian portraiture, therefore, are littered with ex-convict faces.

The oeuvre of the twice-transported, itinerant Tasmanian portraitist Charles Henry Theodore Costantini (1803–1860) is populated almost entirely by sitters of this cast, and even painters at a higher end of the accomplishment and social scale, such as Henry Mundy (c. 1798–1848), could ill afford to be so discerning as to exclude emancipists from their clientele. The subject of Mundy’s wonderful Elizabeth, Mrs William Field, for example, was transported to New South Wales in 1805 for stealing cotton and lace. Her fabulously well-off pastoralist husband was an erstwhile thief and convict too. In Sydney, Richard Read Junior (1796–1862) – who styled himself thus so as not to be confused with his shameful convict pater – dared not discriminate. His sitters spanned the social spectrum, from members of eminent, untainted families like the Blaxlands, to ex-convicts, their wives and children: Jane Penelope Atkinson, for example, the daughter of ex-convict entrepreneur Mary Reibey; or Sarah Cooper, the third wife of gin baron and convicted smuggler Robert Cooper.

William Strutt (1825–1915), replete with French academy training and impeccable draughtsmanship, arrived in Melbourne in July 1850, his timing falling nicely with Victoria’s formal separation from New South Wales and the discovery of one the globe’s richest alluvial goldfields roughly a year later. Both events created prime conditions for personal pride and reinvention – and hence portraiture. Among Strutt’s sitters was John Pascoe Fawkner, one of two former Van Diemonians of occasionally shady character who claimed fatherhood of Melbourne. Fawkner encouraged Strutt to see the newly-minted colony as the stuff of history painting, the artist’s métier; he commissioned the artist to create a full-length portrait in 1853, and in 1856 commissioned a pair of half-length paintings of himself and his wife, Eliza, whom Fawkner claimed to have scored straight off the ship that had transported her to Hobart in 1818. She was then a mere seventeen years old, convicted, so it’s said, of ‘stealing a baby’. Strutt’s masterful picture of Eliza is one of a solidly respectable lady, dignified, seemingly knowing and pragmatic, someone for whom colonial life had provided a route out of difficulty and ignominy. Likewise, with her ringlets and demurely concealed décolletage, Elizabeth Archer is hardly the saucy and intractable strumpet suggested by the Rajah’s conduct record, but the admittedly more prosaic, contented and comfortable young wife of a presumably reformed and effective provider. She died in Maryborough, Victoria, in May 1884, her death notice describing her as ‘a native of Hobart’.

Mirroring the spirit, or semblance, of renaissance and atonement found in many nineteenth-century Australian portraits, Melbourne artist Bern Emmerichs (b. 1961) has created a series of works inspired by The Rajah quilt and its makers for the National Portrait Gallery’s 2018 exhibition So Fine: Contemporary women artists make Australian history. Through her work, typically employing painted and fired ceramic tiles, Emmerichs conducts a feisty mining and recasting of Australian history and the reimagining and recreation of portraits of its various idols, Bennelong, William Bligh and the Macquaries being some of her subjects to date.

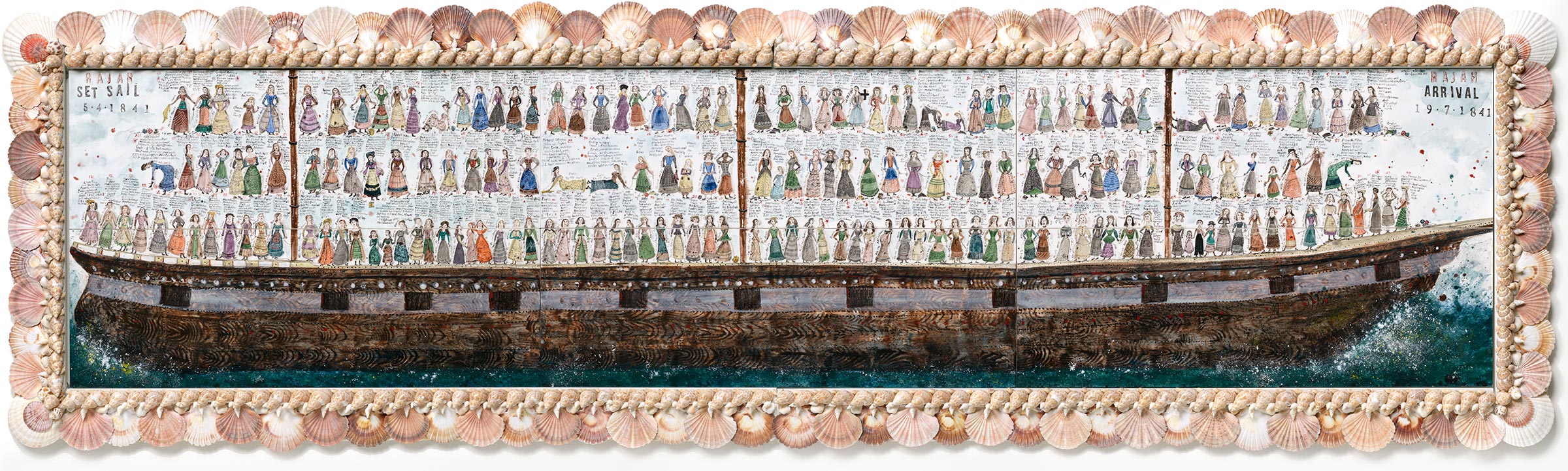

In the same vein, her take on the ship and its voyage includes Cross Stitched, in which the Rajah story’s foremost female protagonists – the trinity of mother Fry, daughter Hayter, and holy ghost Franklin – are presented in a cruciform arrangement centred on a scaled-down ceramic version of the quilt. With Ruffles on the Rajah she reinstates the identity of each of the vessel’s convict passengers, pairing 180 individual portraits with a tiny transcription of their appearance and disposition as noted in the official record. Age, height, eye colour, hair colour and complexion; degree (or lack) of literacy; their trades, behaviour and misbehaviour. Each woman is individually, painstakingly delineated – down to the minute variations in the fabrics and style of their frocks, the myriad freckles, dimples and gestures – and arranged in a rhythmic pattern which mimics the nature, construction and intricacy of the quilt itself. Simultaneously, Emmerichs’ work references the meticulousness and patina of miniature painting on ivory, the crude yet somehow insightful economy of likeness found in scrimshaw and convict love tokens, and the work of the self-taught ‘plain’ portraitists plying their trade among honest, God-fearing folk in supposedly godforsaken, peripheral places. It is in this rich combination of biography, art and history that Emmerichs most palpably evokes not just The Rajah quilt, but several of her colonial artistic antecedents. Collectively, they have stimulated the retrieval of the many possible contributors to the quilt’s making, pleasingly piecing together a portrait of a community of women otherwise at risk of remaining adrift, and welded to the unadorned or scornful facts of official records.

Related information

So Fine

Contemporary women artists make Australian history

Previous exhibition, 2018This exhibition features new works from ten women artists reinterpreting and reimagining elements of Australian history, enriching the contemporary narrative around Australia’s history and biography, reflecting the tradition of storytelling in our country.

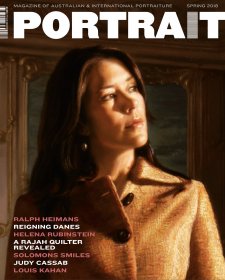

Portrait 60, Spring 2018

Magazine

Ralph Heimans on his portraits, and features on Louis Kahan, Helena Rubinstein, Judy Cassab and Tasmanian convicts.

A guy from Paris

Magazine article by Dr Sarah Engledow

Sarah Engledow on a foundational gallery figure who was quick on the draw.

![In prison and ye came unto me [Portrait of Elizabeth Fry, Newgate Prison], 1820 by Richard Dighton In prison and ye came unto me [Portrait of Elizabeth Fry, Newgate Prison], 1820 by Richard Dighton](/files/5/a/e/0/i11547-th.jpg)