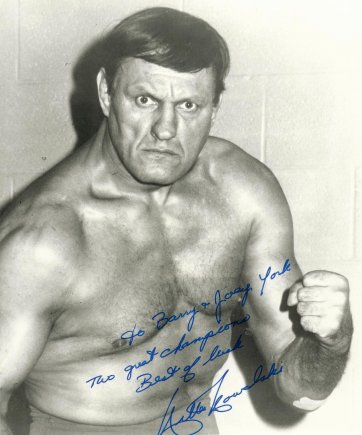

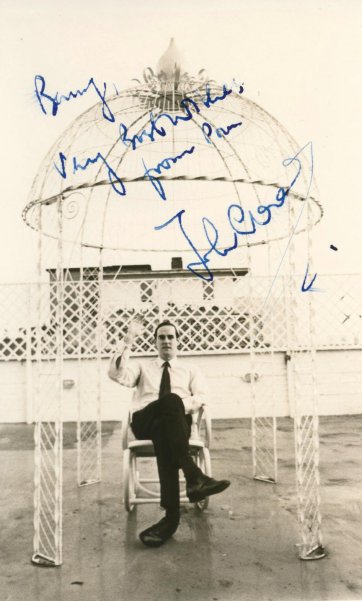

I first wrote to a celebrity in 1964, at the age of twelve. Back then I couldn’t have imagined that, several decades later, I’d have amassed well over a hundred signed photographic portraits of film and television actors, as well as those of a few musicians and wrestlers. Each portrait I’ve collected is fascinating, both in terms of the image itself and its accompanying tale. The back-story is inseparable from the image; the context completes the picture.

My collection is essentially a product of the isolation and loneliness of an only child. I grew up in a working-class migrant family in the Melbourne suburb of Brunswick in the 1960s, a latchkey kid in an unhappy home. Television was to become my escape.

My parents purchased a television set – a Pye 23 inch – in 1960. Dad, Loreto, worked in a factory and Mum, Olive, in a photographic studio. The TV cost the equivalent of a combined ten weeks’ income, but it was worth every penny. The box not only provided an escape, but was also a great educator. One might read about the horrors of Apartheid in South Africa, or the threat of nuclear war, but television brought them into our lounge-rooms, bathed in the flickering pale blue light of a cathode ray tube.

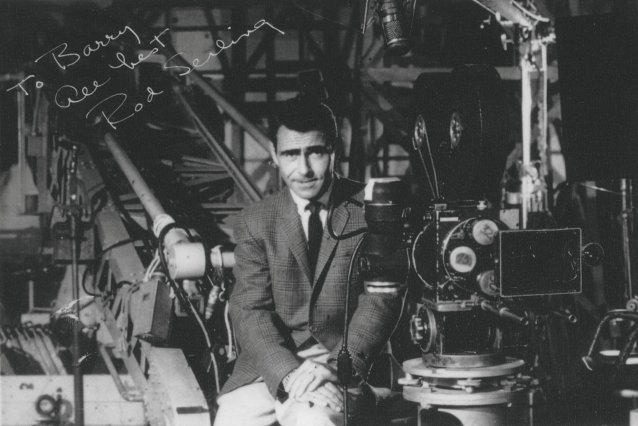

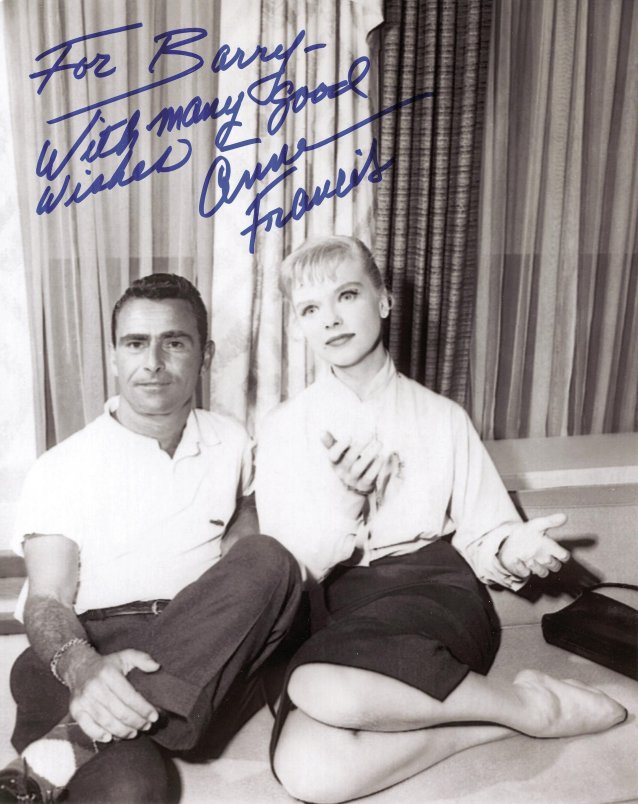

Around 1961, a year after its first airing in America, a program came to Australia called The Twilight Zone. Its creator and main writer, Rod Serling, hosted the show, which took viewers on a ‘journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination’. Those were the opening words from narrator Serling, who employed a fantasy/sci-fi dramatic format to raise social issues. It was radical, even subversive, for its day. Is reality all it seems? My mind went wild with that question and, later, its corollary: can people create a different, better, world? How eagerly I awaited each new story in the anthology!