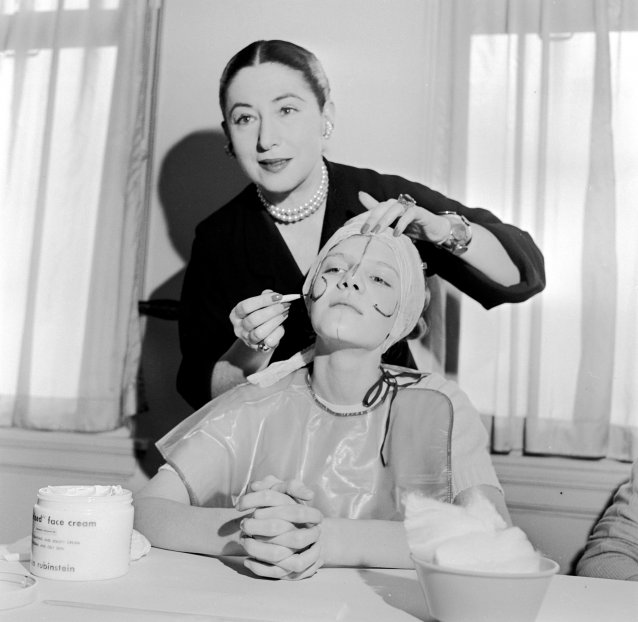

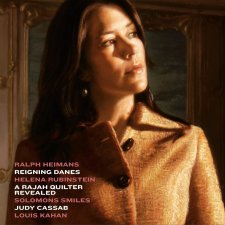

Helena Rubinstein (1872–1965) was the first self-made multi-millionairess of modern times, and created the first publicly-listed global cosmetics corporation. That empire began its life in 1902 as a single upstairs room in Elizabeth Street, Melbourne. Three of Helena Rubinstein’s uncles had emigrated from Kraków via London to Victoria between 1870 and 1886, and established a mixed business in Coleraine in the Western District of Victoria. She followed them, unaccompanied, in 1896. She seems to have become convinced that lanolin from local fleeces might be used to improve and adapt the twelve pots of her mother’s face cream she brought with her from Poland. In 1902, Helena Rubinstein established her first salon de beauté at 138 Elizabeth Street, supplying skin-nurturing ‘Crème Valaze’. That product purportedly contained rare herbs gathered in the Carpathian Mountains, together with essence of almonds and the bark of an evergreen tree. It was said to have been formulated by a Hungarian chemist, Dr Josef Lykusky, and imported from Russia. In fact, the recipe consisted of lanolin, ‘vegetable oil, mineral oil and wax’, and was produced locally with the aid of Felton Grimwade in Flinders Lane. Dr Lykusky was almost certainly fictitious.

Helena Rubinstein had a genius for business. She grasped from the outset that her products needed to be expensive – that working women thirsted for luxury, and would pay for it. Her products also needed to be seen as ‘scientifically formulated in the laboratory’, and obviously they needed to work. She understood the need to emphasise the use of ‘natural ingredients’, even though she was an aggressive adder of bleach and other synthetic agents. At the same time, she was prescient in insisting that prolonged exposure to the sun was harmful to the skin. She also insisted upon maintaining opulently furnished, well-staffed flagship salons (‘instituts’ de beauté Valaze) so as to create widespread fascination with her products. In fact, the vast bulk of her products were sold through department stores. Within fifteen years she created an unprecedented mass market; she built and supervised factories, and tightly controlled every aspect of her ‘brand’. Above all, she understood that she herself needed to project personal glamour – in costume, maquillage and coiffure – to attract sustained publicity. Her astonishing wardrobe was wholly strategic, beginning with the House of Worth in Paris, and continuing through Paul Poiret, Jacques Doucet, Captain Edward Molyneux, Lanvin, Chanel, Schiaparelli, Dior, Givenchy and Cristóbal Balenciaga.