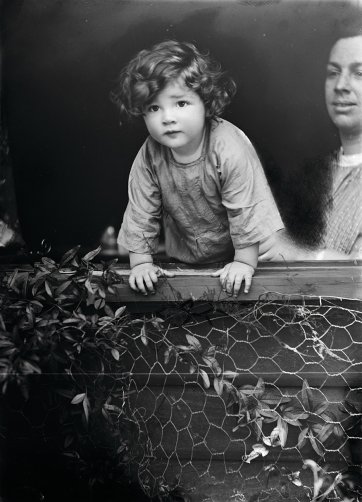

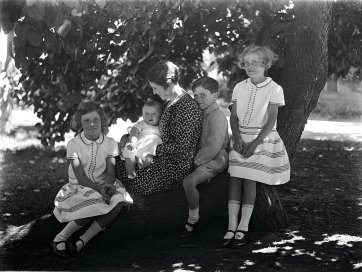

Ruth Miriam Hollick (1883-1977) was born two years before General Gordon perished at Khartoum; she died three years after Abba won the Eurovision Song Contest. As an artist and photographer she was formed in Melbourne through the Edwardian decade, having been taught at the National Gallery School by the ageing Frederick McCubbin, of whom she became fond. Hollick began her career as a peripatetic portrait photographer in about 1908 when she bought a small car and travelled throughout the Western District of Victoria and the Riverina. On these extended trips she produced mainly group portrait photographs of and for families, particularly of mothers with their children.

Natural, artistic and unselfconscious

by Angus Trumble, 22 December 2016

At the same time Hollick developed a particular skill in harnessing effects of natural light in sometimes difficult circumstances, making the best of very often limited time and what few resources she had at her disposal. All this stood her in good stead when, with her professional and personal partner Dorothy Izard, Hollick took over a city studio, first in 1918 in the Auditorium Building at 167 Collins Street, Melbourne, and subsequently expanding onto a whole floor of Chartres House at 163 Collins Street, an establishment replete with wellappointed reception rooms.

According to one surviving account, ‘The studio is a picturesque room, with a huge fireplace filled with rough pine logs and fir cones, and with a basket of fir cones at one side. Slanting windows are veiled with ivory muslin, or curtained with dull green and blurred cretonnes. Jars of golden broom and damask roses are arranged about the room’. This evidently doubled as an exhibition space, at times densely hung with Hollick’s portraits of children.

At the opening of one such exhibition in 1928, Mrs JG Latham (wife of the Attorney- General and Minister for Industry in the administration of Stanley Bruce) was reported as saying: ‘I am very glad to congratulate two women who have been such a success in their profession. Within our own time a great change has taken place in regard to women’s work, and it is now universally acknowledged that a woman has the right to earn her living in any profession she may select. Whether all professions are equally suited to women or whether they will be supported in all professions is open to question, but I think we can all agree that in such a career as that of photographic art they may be said to excel. We congratulate Miss Hollick on what we see here to-day, a succession of child portraits at once natural, artistic, and unselfconscious.’

Through the 1920s and early 1930s, in partnership with Dorothy Izard, Ruth Hollick attained success as the most prominent professional society portraitist and fashion photographer in Melbourne.

Her work appeared regularly in the pages of Table Talk, the Bulletin, Lone Hand, Home and the Australian magazine. She was much sought after for advertising assignments. Her work was also regularly exhibited in solo and group exhibitions, including the Chicago Photographic Exhibition and London Photographic Salon of 1927 and the Amateur Photographer Overseas Exhibition in London in 1932.

Having reached the pinnacle of success, the Great Depression all but destroyed Ruth Hollick’s business, though she continued to work from home in Moonee Ponds. World War II subsequently destroyed her clientele. Post-war fashion, photographic style and habits of life, meanwhile, simply left her behind. Ruth Hollick retired in 1958. She was a Christian Scientist.

Because such a large proportion of her work vanished into the domestic sphere and sat on mantelpieces and side tables or hung over fireplaces—with luck passing thence into the hands of appreciative descendants, but more usually ending up in opportunity shops or worse—in subsequent decades Ruth Hollick’s work was barely visible except to a small circle of enthusiastic students of Australian photographic history.

Her sometime success and prominence were all but forgotten, except for her brief reappearance (in decidedly mixed company) in the 1981 exhibition Australian Women Photographers, 1850-1950 at the George Paton Gallery. Though in her heyday Ruth Hollick and her work were often mentioned in the social pages, and often reproduced, her voice and that of Dorothy are completely silent.

Related information

Portrait 55 , Summer 2016-2017

Magazine

Explore convict art, photography by Ruth Hollick and Collier Schorr, an interview with neurosurgeon Charlie Teo, portraiture on money, and more!

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

Support your Portrait Gallery

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!

![Oxlade Woman’s World [illustration for Women’s World] by Ruth Hollick Oxlade Woman’s World [illustration for Women’s World] by Ruth Hollick](/files/e/9/d/e/i9849-th.jpg)

![Dame [Nellie] Melba by Ruth Hollick Dame [Nellie] Melba by Ruth Hollick](/files/8/e/1/0/i9840-th.jpg)