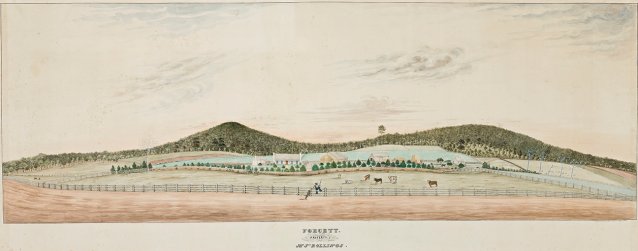

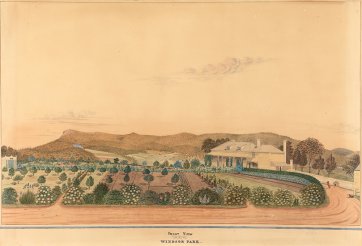

The fact that his passing got a mention in the papers wasn’t necessarily an indication that George Bellette was considered a distinguished or exceptional citizen. ‘The deceased gentleman was 74 years of age’, stated Launceston’s Daily Telegraph of the 24th of March 1885, ‘a quiet, inoffensive man, [who] had all his lifetime followed the pursuits of a farmer’. The Hobart Mercury likewise mentioned little more than his farming career, many friends and few enemies. Seemingly, it was the long, blameless and inconspicuous nature of Bellette’s life that made his death worth noting. As an ‘old colonist’ – to use the descriptor that often connoted those whose origins were in convict times or ex-convict stock, or both – it’s as if he was noteworthy in being ordinary, or for being an illustrative study in Tasmania’s transition from blighted penitentiary to prosperous, if prosaic, province. Born in Hobart to parents whose misdemeanours had originally seen them exiled to Sydney, and from there to Norfolk Island, Bellette was from one of the many Norfolk families who thrived after relocating to Van Diemen’s Land, and a classic example of the colonial-born man of modest means made good.

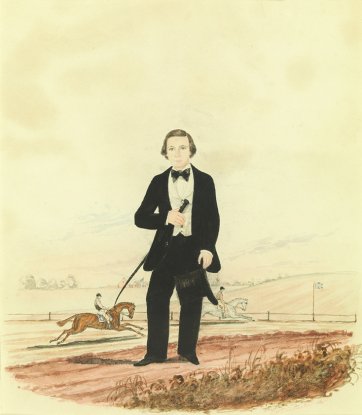

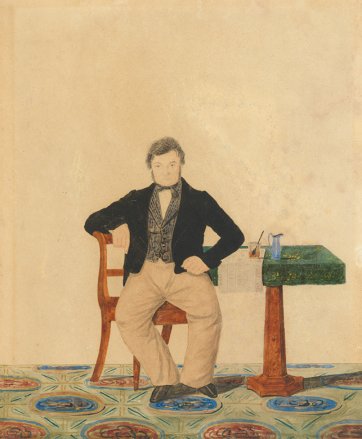

This also made him a member of the group regularly captured by portrait painters; the artists were capitalising on those conditions that gave the socalled middling classes access to the ownership of land, houses and the usual accoutrements of honest domesticity. As the Royal Academician Henry Fuseli once whined, whereas portrait painting was formerly ‘the exclusive property of princes, or a tribute to beauty, prowess, genius, talent’, by the nineteenth century it had been downgraded to ‘a kind of family calendar … of parents, children, brothers, nephews, cousins, and relatives of all colours’. Having one’s likeness taken, by this estimation, was an exercise in sentimentality and consumerism, an opportunity to project gentility and identity through the documentation of one’s self and one’s stuff.