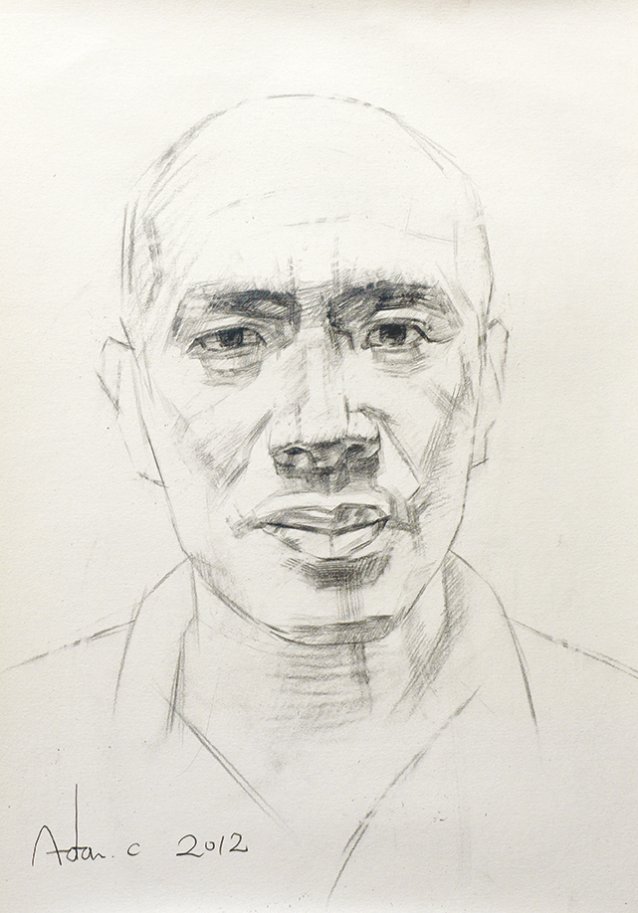

Professor Charles ‘Charlie’ Teo is passionate about brains and the people they belong to. It might seem an obvious statement to apply to Australia’s most well-known neurosurgeon – and one who’s transcended pure clinician status to become a celebrity of sorts – yet so many people, high-profile or otherwise, pursue careers as a function of beige-infused motives such as remuneration, status or blunt familial pressure. The earnest, endearing zeal that Teo projects as he speaks banishes any such possibility in his case. I’m here at his rooms at Prince of Wales Hospital in Randwick with colleagues from the National Portrait Gallery to film a Portrait Stories interview. The Gallery acquired an arresting painting of the neurosurgeon by multiple Archibald finalist Adam Chang in 2013, and, as the conversation flows, it becomes an intriguing experience reconciling the pensive, almost vulnerable countenance of the sitter in Chang’s layered-blue work with the live version before us.

We start by asking about Teo’s early days, where we discover we might have lost the neurosurgeon to the lure of another field requiring ample skill and dexterity: ‘My mum tells me that when I was a child I use to look out the window when the garbage men would come by. They're very athletic, wearing singlets with big muscles, jumping up on the back of the truck and looking incredibly active and fit. I used to aspire to become a garbage man when I was a young fellow!’ The simple pleasures of physical exertion were to lead to a black belt in karate later on, and Teo pursues a dedicated regime to this day, incorporating kayaking and swimming. He explains that the fitness is crucial to ensure he is at his best for surgery; to emphasise the point, the lean fifty-eight year-old is clear and concise despite speaking to us after only a few hours sleep, having performed a six-hour operation the previous night. ‘It's six hours of staring down the microscope, perfectly still, arms up like this the whole time and not resting, and concentrating on someone’s life in your hands.’ It strikes me as a gruelling stint, but in fact his longest ever operation was over four times as long, clocking in at a brutal twenty-six hours.

Teo credits the influence of his mother – a ‘tiger mum’ and ‘his biggest inspiration’ – as providing the first push towards medicine, but it was his initial love of the field in challenging circumstances that drew him onwards and upwards into the lauded career to follow. He notes ‘the first time I was exposed [to neurosurgery], I was doing paediatric neurosurgery ... As a registrar, you are basically the man on the ground at the call phase. You see all the emergencies; you see the kids that come in with bad head injuries that you've got to try and salvage in the emergency room, and often you’re operating on your own. Yeah, I was thrust in the deep end, but I loved it.’

The evolution of Teo’s career now sees him operating and teaching pro bono in developing countries for several months a year, as well as promoting the Cure Brain Cancer Foundation, which he founded. His caseload is made up predominantly of patients afflicted with brain tumours that are deemed (by other surgeons) ‘inoperable’. For many people, Teo is the ‘last chance saloon’, a desperate detour from grim euphemisms such as ‘putting your affairs in order’. It’s his willingness to operate in these cases that has drawn enormous acrimony from many of his peers, with labels such as ‘maverick’, ‘cowboy’ and ‘narcissist’ bounced around, as well as accusations of ‘offering false hope’. The patient stance is rather different; there is a long list of testimonials from sufferers and families lavishing praise upon him in instances where Teo has extended and indeed saved lives. The duality of perspective is genuinely stark.