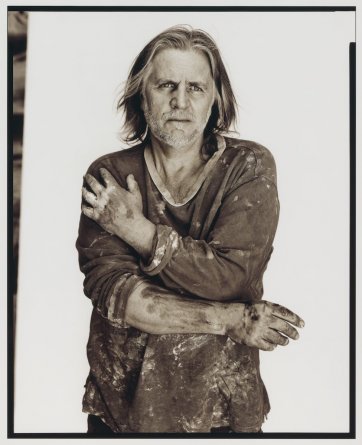

Gittoes’ interest in filmmaking intensified during the 2000s. In 2003 he travelled to Iraq to film Soundtrack to War, a confronting documentary examining the significance of music for young soldiers during wartime. Three years later Gittoes filmed Soundtrack’s sequel, Rampage, in Miami’s notorious Brown Sub (Brownsville) ghetto. Most recently, Gittoes has established an artists’ co-operative in the heart of Jalalabad, affectionately named the Yellow House after the Australian collective. Far from representing a peaceful example of ‘coming full circle’, Gittoes’ decision to found an Afghan iteration of his Sydney alma mater demonstrates his undimmed commitment to engaging in a no-holdsbarred interrogation of the human condition as it exists within conflict zones.

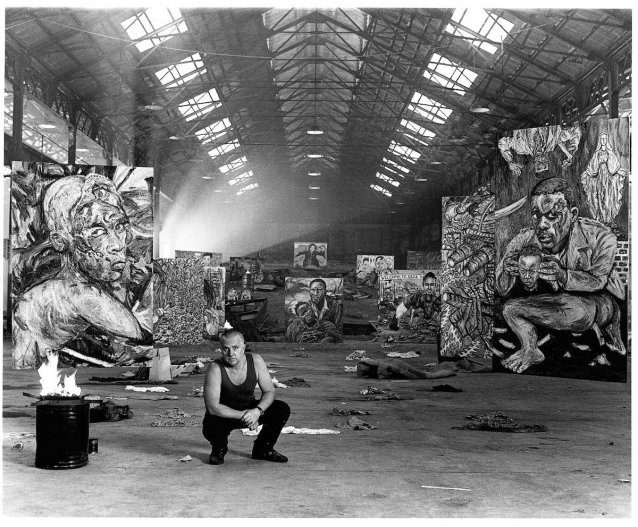

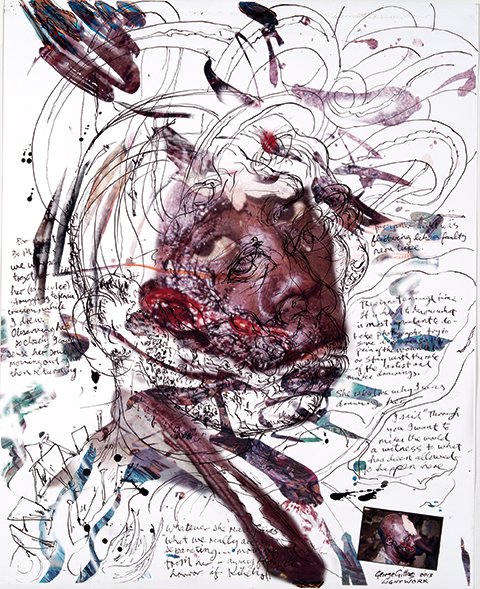

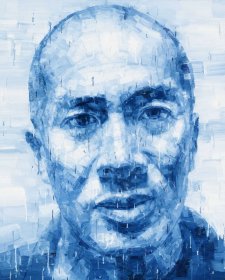

Gittoes’ career and body of work reflects his interest in critically engaging with war and conflict. The artist explains that his approach to representing carnage is informed by an adamant refusal to ‘ignore any trauma’, claiming, ‘I’ve always put human life and helping people in front of shooting my film or taking my photographs or drawing’. Gittoes’ assertion is supported by Paul Jordan, a former SAS soldier who first encountered the artist in Rwanda in 1995. Jordan and Gittoes were both present at the Kibeho massacre, one of the bloodiest episodes of the genocide, where at least 4000 ethnic Hutus were brutally slaughtered by the Rwandan Patriotic Army. Jordan states, ‘He knew when to take photographs and when to help save a life – and he didn’t flinch. The horror of seeing women and children hacked to pieces didn’t stop him; seeing decapitated babies still strapped to their mothers’ backs didn’t stop him.’ Art critic Joanna Mendelssohn argues that this quality sets Gittoes apart as a war artist. She contends, ‘The trick with Gittoes’ art, and why it rises way above that of those artists officially commissioned to record the Australian army at work, is that he draws what he feels as well as elements of what he sees’. Fascinated with human stories and individual faces, Gittoes has developed a multi-media approach to figurative art that works towards providing insight into the complex, often tortured and sometimes inspiring nature of humanity in conflict-ravaged settings.

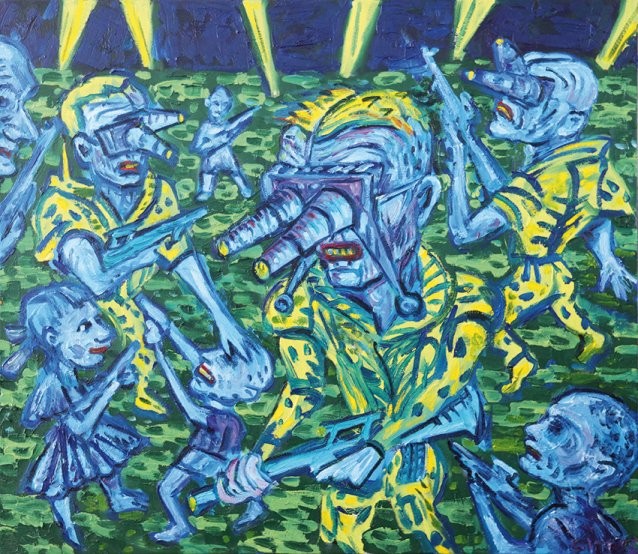

Gittoes’ art practice reflects his conviction about the integrity of imagined representations of trauma. ‘All the frontline war journalists I know who have really been there, insist that artists see things very differently and that emotion and imagination can be as truthful as facts and film.’ Elaborating on this statement, Gittoes turns to a painting created during his visit to a drought and civil war-stricken Somalia in 1993. Rather than providing a strictly accurate depiction of soldiers in action, Night Vision Baidoa’s aesthetic captures the emotive sensibility of Gittoes’ experience of accompanying a local Somali night patrol.