In 1947 and 1948, Perceval and Boyd integrated known places and the people who inhabited them with images from several centuries before, translated via the treatment of similar subjects in modern Europe. Perceval’s interest in the work of Hogarth also becomes most evident at this time. Indeed, an account of Hogarth’s aims and art might read as if referring to Perceval. There is an interest in literary allusion, the telling of a moral tale, plus occasional topical reference, as well as the inclusion of characters telling of the artist’s life. Certain vignettes revive the ‘conversation piece’, of which Hogarth was a major exponent. As the English variant of the Dutch genre style, the focus is on one or more family members and friends engaged in a common domestic routine, or, as was often the case, an outdoors activity. But Perceval frequently replaced a literary reference with iconographic or thematic elements from twentieth-century cinema.

In keeping with the Hogarth model, Perceval’s friends and relations are often identifiable. Tom Sanders, later to become a fellow potter at Murrumbeena, sits at the right-hand side of Christ in Christ Dining at Young and Jacksons. Perceval appoints himself as Simon Peter, who taps Saint John on the shoulder in Leonardo’s Last Supper (1494–98), and someone looking like Albert Tucker asks for more. A table is about to be turned and money spilt, as in the ‘Cleansing of the Temple’ parable, in which Jesus is said to have driven out the moneychangers. Betty Burstall, married to the filmmaker Tim Burstall, and later known for her work as theatrical manager of La Mama in Melbourne, is portrayed as the serving girl. It is not surprising she gets a starring role in an all-male biblical story, as there had been an affair. Tim had worked as a ceramics decorator at the Arthur Merric Boyd Pottery, and the Percevals and Burstalls became close friends. In a milieu of constant social interaction, from the mostly male pursuit of drinking at the Swanston Family pub – on the corner of Swanston and Little Bourke streets in Melbourne – to parties at one another’s houses, Perceval developed a clandestine affair with Burstall’s wife, Betty, but, unbeknown to him and Burstall, they were both having affairs with each other’s wives.

Tintoretto’s disciples in The Last Supper (1592–94) are so dramatic in their expression of sorrow for Christ’s earthly demise that Perceval’s, by comparison, appear overly casual. They are again quite unlike the restrained men who attend the table in Leonardo’s Last Supper. Perceval’s facetiousness in setting his dinner in Australiana also involves art historical detail beyond the obvious Leonardo and Tintoretto antecedents. He built archways into the Young and Jackson dining hall, as El Greco did in Christ Cleansing the Temple (c.1570), and placed an Australian counterpart to the sculptural reliefs that El Greco included as his homage to an earlier master. Melbourne’s notorious nude Chloé, painted in 1875 by Jules Lefebvre, is seen through the far arch. The irony of her notoriety would not have escaped Perceval, since she is naked and adored, but her genitals are not included, as if ‘air-brushed out’ by the artist.

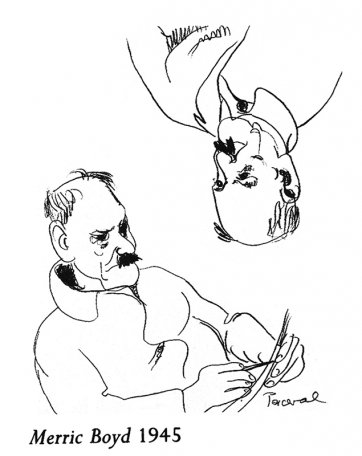

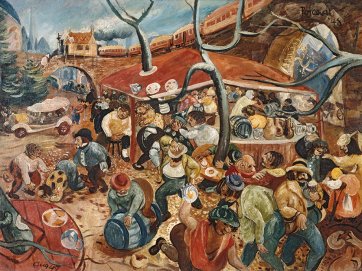

An unflattering sketch of Arthur Boyd standing beside the Dodge car he passed on to Perceval is shown at centre left of The Revellers (1947–48). In mood and general composition, the scene refers to The Peasant Wedding Dance (1607) by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, who based his work on a peasant wedding dance painting by his father. From the younger Brueghel comes the basic composition, including the deciduous tree trunks, the central table and the milling crowd, but the scene is also late afternoon at Melbourne’s Rosstown Hotel at 1084 Dandenong Road, Carnegie. It was the hotel’s proximity to the Murrumbeena pottery that led the potters to join its crowd in the late 1940s. Barry Humphries (lower right) and a balding man with white hair hold onto each other as they share a joke.