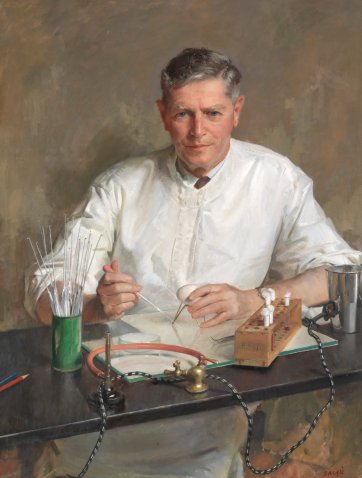

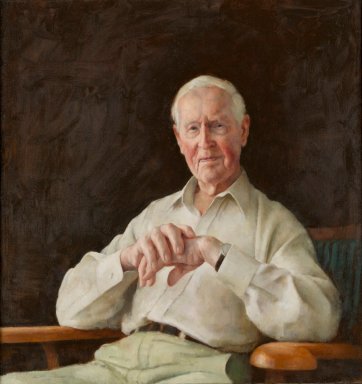

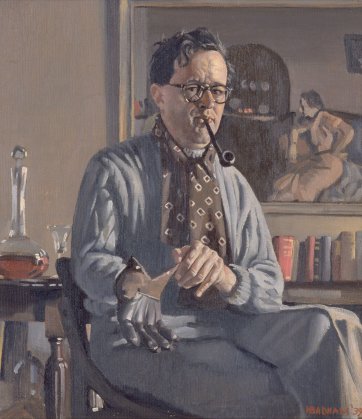

When they appear in portraits, and they appear very often, hands may perform any number of useful functions. They can be set to work doing something useful. They can be exploited as a refinement or elaboration of elements of the character of the sitter. They can enhance the composition through gesture—demonstrative, particular or vague as the case may be. They can place real emphasis upon qualities of grace, strength, endurance, frailty, delicacy or plain old age. They can be made to hold onto something, or to let it go. They can be clasped, or in repose. And the hands can be brought into suggestive dialogue with the face itself. As Montaigne put it (in 1580),

What doe we with our hands? Doe we not sue and entreat, promise and performe, call men unto us and discharge them, bid them farewell and be gone, threaten, pray, beseech, deny, refuse, demand, admire, number, confesse, repent, feare, bee ashamed, doubt, instruct, command, incite, encourage, sweare, witnesse, accuse, condemne, absolve, injure, despise, defie, despight, flatter, applaud, blesse, humble, mocke, reconcile, recommend, exalt, shew gladnesse, rejoyce, complaine, waile, sorrow, discomfort, dispaire, cry out, forbid, declare silence and astonishment: and what not? with so great variation, and amplifying as if they would contend with the tongue.