Karen-Jane Eyre was the magazine’s editor for over twelve years. She liaised with sitters for the nude celebrity portraits, commissioned the photographers and produced the shoots. This involved, at times, dozens of phone calls to agents in Australia and overseas, and meetings to develop the shoots’ concepts with sitters. ‘I spent a lot of time talking with them about the image they would like to project’, Eyre says. She used to remind herself ‘it was a big decision for people to consider posing for a magazine like this – but they were always flattered to be asked’.

All the photographers I interviewed recalled the positive collaborations and creative freedom when shooting for black+white. Eyre explained the process: ‘Every shoot was a team effort, but someone had to be in charge’. Eyre selected and briefed photographers and discussed mood and styling. She then worked with the photographers during shoot production – booking hair and makeup, stylist, studios, props, locations and managing the budget. ‘My final responsibility’, Eyre remembers, ‘was working on selecting the images to be published with black+white’s Art Director and Creative Director, Marcello Grand, and then getting sign-off from the talent.’

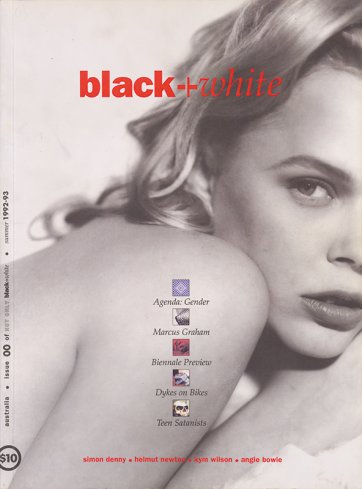

black+white existed in the moment between ‘the mass media’ and ‘social media’. The ‘information super-highway’ was under construction. As technology was recalibrating lives and cameras to digital black+white thrived in analogue. It straddled the end of the millennium. Frozen in its undigitised, copyright-locked 1990s/2000s time capsule, very little exists online about the magazine, where it is, oddly, easier to research the first decade of the 20th century than the last. Reliant on those who remember it, I wish I could have talked with every contributor to black+white – not least so I could thank them personally for a magazine that was so important to me. I could not get in touch with black+white’s visionary founder and Creative Director, Grand.

Much discussed at the time, public, personal and media opinion was divided on the line between art and provocation. ‘Looking at the naked body extends the boundaries of our perceptions about who we are … black+white continues with its agenda to demystify the body, thereby revealing the true nature of our humanity’, wrote Eyre in #4 in 1993. Not all saw it this way. Bleddyn Butcher’s portraits of musicians Dave Graney and Clare Moore were shot for the 1997 ‘musicians’ special issue, and are held in the Gallery’s collection. In a recent ‘Portrait Story’ interview for the Gallery, Graney says they are unrepresentative out of context, as they did the shoot regaled in cuts of meat as a joke, and in a pointed subversion of what they saw as plain voyeurism clothed in ‘‘90s pompousness’. For black+white, the freedom to have this argument was part of the point. That special issue’s introduction asked: ‘Legitimate or gratuitous? Tasteful or titillating? And does it matter anyway? It’s all a question of personal aesthetics.’ Its aim was ‘to extend the boundaries of the Australian celebrity portrait’.

Revisiting the magazines a decade on, the portraits taken as young stars’ big careers were taking off are peculiarly powerful. Andrew Craig Steinman transformed Portia de Rossi into a post-modern Botticelli sprite – all tousled hair and flooded projected text; Tony Duran photographed Naomi Watts as an 18th century beauty in a verdant European garden; Guy Pearce’s shoot with Simon Anderson bathed the effervescent co-star of Priscilla in subdued light and shadow. Nude portraiture was able to simultaneously reflect these sitters’ physical beauty, youthful vulnerability and striking confidence in pursuing their ambitions.

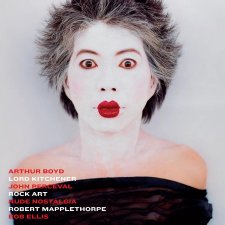

Design studios in London, fashion designers in Paris and photography studios in New York noticed black+white. Top international photographers, including Helmut Newton, Herb Ritts and Ellen von Unwerth, attracted by the quality of the design, paper and printing, began sending work. ‘We could never have afforded them had they not been submitted’, says Dent. ‘No one realised how small the budgets and team were.’ black+white was widely imitated. By around 2005, half its sales were international. The magazine had an air of glamour as its reputation grew through the 1990s. ‘People thought that we must have naked women racing around the offices – that never happened!’ laughs Dent.

black+white’s artistic integrity secured its sitters. ‘Frankly, pornography bores me, but nude photography, when it’s done well, is a different thing. The naked body is beautiful’, asserted Kym Wilson in #00 – an observation echoed through the years. Annalise Braakensiek agrees. Responding to my request for permission to print her beautiful portrait by long-standing photographic duo Lyn Balzer and Anthony Perkins, from #26 in 1997, she wrote to me: ‘I am a lover of art. I respect Mother Nature and the body I have been given. The human body is itself a work of art. For me nudity and posing for, or admiring, artistic photography is nothing to be ashamed of – quite the contrary.’

For Balzer and Perkins, ‘without clothes there is an honesty and a pure sensibility – there can be a storytelling aspect to the shoot, as opposed to documenting the clothes’. They provided these insights via Skype from their warehouse studio in Sydney (around the corner from where the Studio Magazines offices used to be). They continue to exhibit photographic nudes internationally. In black+white, this freedom from clothes released the storytelling potential of photographic portraiture for many of its sitters. Of photographing twenty-one year-old Natalie Mendoza, the star of stage musical Les Miserables (for #32 in 1998), they remember ‘a beautiful pared down shoot’. Director Baz Luhrmann subsequently saw the portraits and cast her in Moulin Rouge.

Mendoza sent me an eloquent reflection on this shoot, describing it as ‘the very first time experiencing a new way of viewing who I was’. She wrote: ‘Lyn and Tony asked me what statement I wanted to make as an artist. It was seductive to all my hidden sensibilities and for that reason it was also most terrifying … I grew up amongst the loud personalities of a large creative family. In that world full of noise I barely spoke as a child. I had an inner life nobody knew of. My fascination with Zen and minimalism was first captured in these early images. I wanted to convey the yin and yang energies – the beauty of antithesis, the world of opposites and all that flowed in between. Art without vanity was such a beautiful and rare jewel of an experience. My inner emancipation had begun.’

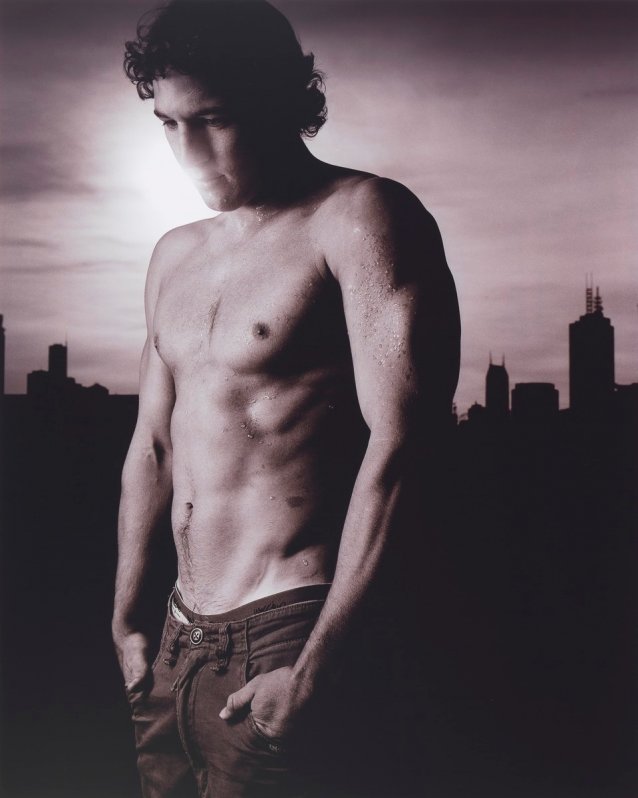

Many sitters grasped the opportunity to capture, for the future, a transient moment of their youth in peak physical condition. In interview after interview accompanying the ‘Starlust’ portraits, the sitters describe being initially nervous, overcoming apprehensions, and feeling liberated. Tony Duran learned a lot about how to work with his sitters from his black+white shoots. ‘I have carried this with me over all these years’, he told me. Duran’s stunning portraits of eighteen year-old Home and Away star Melissa George were published in February 1995. In her interview with Athena Thompson, George spoke of the chance to be seen in a different light; she identified with the strong feminine aesthetic and story of Tamara de Lempicka, a quasi-cubist painter of the 1930s, and plotted the shoot with Duran accordingly. Twisted into angles and precisely controlled shapes, George’s smooth luminous form, unified by dramatic gesture or fiery look, re-enacted the artist’s forms. ‘On the day of the shoot she worked her butt off’, Duran said of the eighteen-hour session. ‘I remember those pictures like it was yesterday.’

Another television star shedding her popular persona in a nude portrait shoot for black+white was twenty year-old Jacinta Stapleton, in #39 from October 1999. ‘Any chance I get to go against the stereotype, I take’, she told Merran White in her interview. Stapleton had recently decided to leave the Neighbours cast. ‘We were trying to get a feeling of looking ahead. All I was thinking, all day, was how I was leaving this part of my life behind.’ Balzer and Perkins remember Stapleton saying she spent the ‘whole Sunday before the shoot naked at home, to get used to it’. ‘She sent us a letter a few weeks later saying the shoot was one of the best experiences she has had in her life, breaking down her own boundaries.’

‘The aesthetic and content stayed true to the original intention and ethos’, Eyre reflects. I wonder if black+white could have existed anywhere else. Eyre thinks it ‘was Australian, without “being Australian”’. Her feeling is that ‘something in the beach culture, the physicality of Australians, the openness of Australian culture meant that the nude celebrity portraiture aspect was unlikely to have evolved elsewhere’. ‘I am such a prude,’ laughs Tony Duran, ‘an Irish Catholic Midwestern uptight guy’ – but black+white, he says, ‘allowed me to go there’. ‘If I had started in America, I would have become a very different photographer’, he reflects. ‘The freedom of Australia, the strong sensuality and confidence rubbed off on me.’

black+white thrived in the environment of cultural confidence and optimism created by the turn of the millennium and the Sydney Olympic Games. The Olympics Special Issues, Atlanta Dream, Sydney Dream and Athens Dream flew off the shelves, according to Dent: ‘They staked out our place in the popular and international markets.’ Stories of ancient Olympians competing naked and the Greek aesthetic of the heroic nude cemented the concept. Over ninety of Australia’s top athletes’ extraordinary discipline, resilience and physiques were celebrated. Photographer James Houston did nine striking shoots for the Sydney Dream. In Houston’s portraits of pole-vaulter Tatiana Grigorieva, she gently descends, twisting her exquisite athletic form in mid-air, one arm trailing up behind her floating blond hair, toes pointed. In her interview, she reflected that as an athlete and as a model: ‘you fly because you want to fly … I can express myself freely but keep total control.’

black+white sought out young talented photographers, even if they had no experience with nude portraiture. Eyre rang Adam Pretty out of the blue to shoot for the Athens Dream. He did a shoot with swimmer Brett Hawke at midnight on a windy, freezing cold Sydney beach. A multi-award winning sports photographer, Pretty works all over the world for Getty Images. He was in Munich when I rang him. Kayaker Nathan Baggaley had never paddled in Sydney Harbour (‘It was like a washing machine out there!’) before doing his shoot with Pretty, who was treading water and dodging ferries under the Bridge. Doing these shoots, Pretty says, opened doors and helped develop his career and practice. Rio 2016 will be his eighth Olympic Games as a photographer.

By the mid-2000s, the culture was shifting. ‘It was a real shame to watch the open, free, liberal environment start gradually to feel constricting and judgemental’, regrets photographer Luke Feltham, who felt this change occurring from the mid-1990s. A consistent contributor to black+white from the beginning, Feltham was working between Australia and Europe, including with Vogue España. Potential ‘Starlust’ sitters were increasingly nervous (and reasonably so, given the dross that fills online ‘comments’ pages) about how their portraits would be distributed and endure. The information revolution had its victims. A sense of personal freedom succumbed to new privacy settings.

‘Celebrity has changed’, observes photographer Michelle Day. Canberra-born Day relocated to Los Angeles in the 1990s to build a highly successful career in celebrity portraiture. She photographed Australians Rebekah Cross (with a live python), Gabrielle Fitzpatrick (in a cloud of feathers) and Max Sharam (as queen of a surreal party), in Hollywood for black+white. ‘This combination of nudity and celebrity would never happen today – the way that celebrities now have to fiercely protect their privacy … never before or again – it was incredible.’ Both Dent and Eyre reflected on the public mood after September 11, the effect of the internet and increasing dominance of ephemeral imagery. It was a different world when a celebrity did a nude photo shoot and it would appear only in beautifully printed hardcopy editions of a magazine. ‘We could feel the change’, Eyre remembers. #88, the last, was published in summer 2006/7. ‘black+white suddenly seemed old-fashioned’, Dent told me.

Could it exist again? Everyone I interviewed for this article agreed – no: not without the physicality of the printed page; not with the internet; not with social media; not with a society that is, maybe partly as a consequence of these things, more fearful and conservative. I wonder how many creative lives black+white touched: the actors, dancers, artists, curators, graphic designers, writers and photographers out there living the legacy of this bizarre relic from a more liberated time. Re-reading the magazines now, I am struck by its unembarrassed candour, and a gentle and hope-filled striving after honesty, strength and humanity through portraiture. I am struck by its assumption of an enduring freedom of creative expression. Sometimes, it is indeed hard to believe it ever existed.