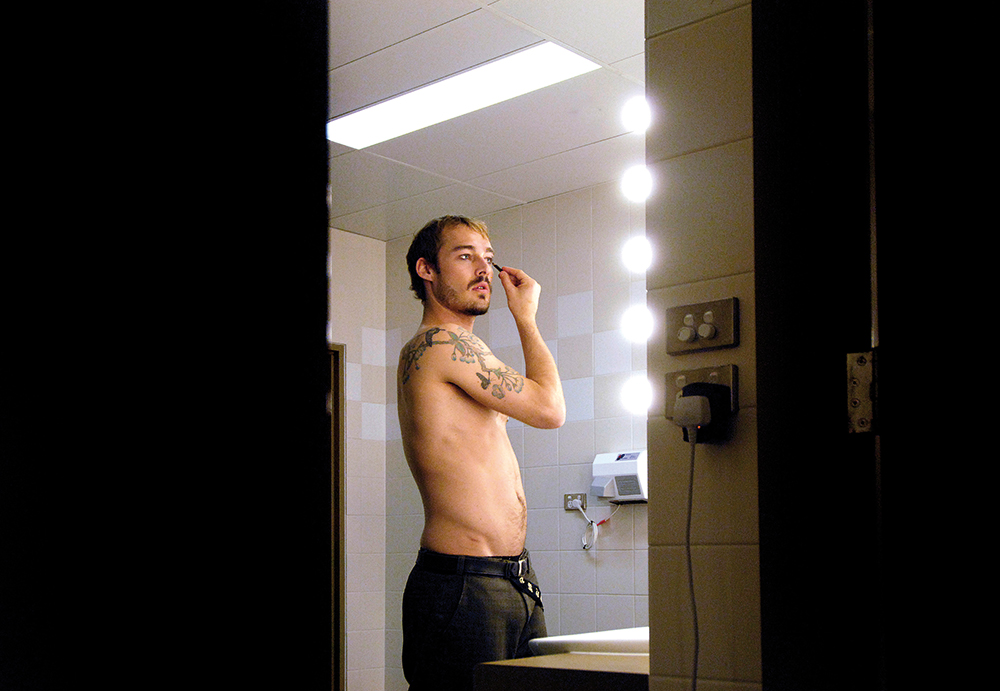

As exciting and captivating as their live images are, arguably it’s the trio’s portrait work that has made each of them so highly sought after in the music industry. However, while Philbey, Hibberd and Boud enjoy the creative process of making a portrait, they all agree that it’s significantly more testing than shooting a live show.

‘It’s a completely different ball game’, says Boud. ‘With live work, it’s presented to you; it’s staged for you; it’s lit for you. You don’t have to give the artist any direction; you just rock up and shoot what happens. But portrait work is a blank canvas. It puts the burden back onto the photographer.’

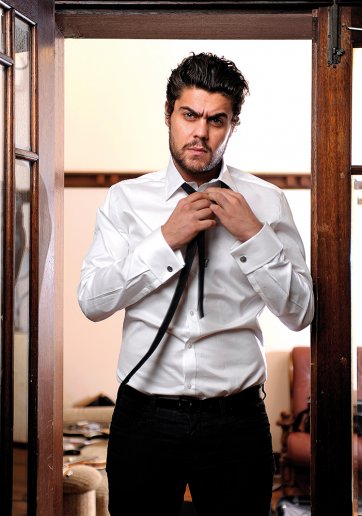

That burden grows a little heavier when you consider that many artists don’t like having their photo taken – they’re musicians, not models, after all – and photographers are often given limited time, particularly when shooting bigger acts. Of course, there are inevitably a few horror stories.

‘Plenty of things can go wrong’, Philbey laughs. ‘I’ve had situations where bands have been up all night and they’re not in a great frame of mind. Or you’ve been told you’ll have twenty minutes and then you only get two minutes. I’ve even had sets built and then had artists walk in and say, “Nah, I’m not doing that!”’

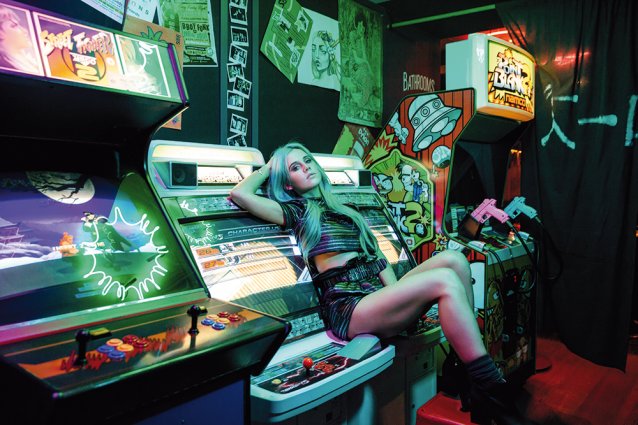

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges for photographers lies in developing new ideas and concepts for portraits. ‘It’s the thing that stresses me out the most,’ Hibberd confesses, ‘especially because I seem to do jobs in blocks. It’s hard to come up with ideas when everything comes in at once.’

To put that in perspective, Hibberd was several weeks into solid, back-to-back shooting when I spoke to him in early 2016. That run of work included eight magazine cover shoots in six days. Moreover, Hibberd does fifty or sixty band sessions each year, and many of those shoots require multiple ideas and concepts. Then there’s the time spent editing images, a commonly overlooked aspect of a professional photographer’s workload, which far exceeds any time spent behind a camera. It’s not easy keeping the creative juices flowing at the best of times, and it’s even harder when the work starts piling up. Boud and Philbey find concept development challenging, too.

So where do the three photographers draw their ideas from?

‘I take a lot of inspiration from movies and TV – how things are shot and framed, and how things are lit’, says Philbey.

‘I steal a lot of ideas from my wife’, laughs Boud, referring to his photographer spouse, Cybele Malinowski, who specialises in fashion and artist portraiture. ‘We both draw a lot of inspiration from the classics like Annie Leibovitz – when she [Leibovitz] does a great shoot, there’s no-one better.’

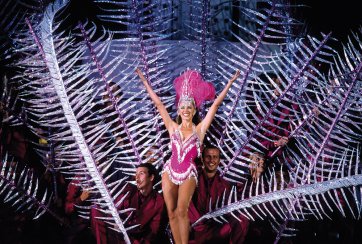

Like Philbey, Hibberd loves cinematography and film. Interestingly, comic books fuel Hibberd’s creativity as well. ‘I love illustrators because they’re not limited by angles’, he explains. ‘They can create whatever perspective they like; they’re only limited by their imagination. I’ll see a drawing and think, “I wonder if I can shoot from that angle or get that composition?”’ However, wherever possible, Hibberd tries to take something from the band’s album and link it to an idea or concept. ‘It’s about giving their voice an image; trying to create something that sums up that band and their music.’

And that, essentially, is what these photographers do through their image-making — they provide a visual interpretation and representation of musicians and their craft. By doing so, they also capture a unique snapshot of culture and society, and the musicians that shape and define so many lives.

But Philbey, Hibberd and Boud do it in such a thoughtful, clever way that their work transcends the simple documentation of a time and a place, featuring famous faces — it stands alone as art. Rock art.