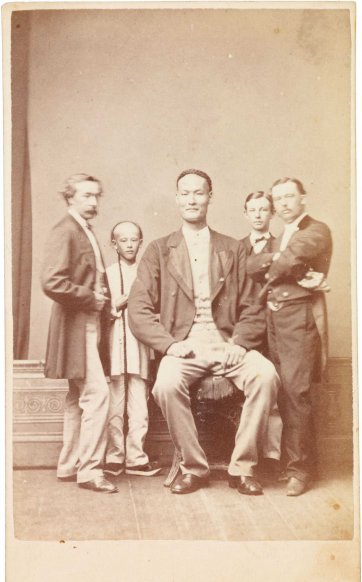

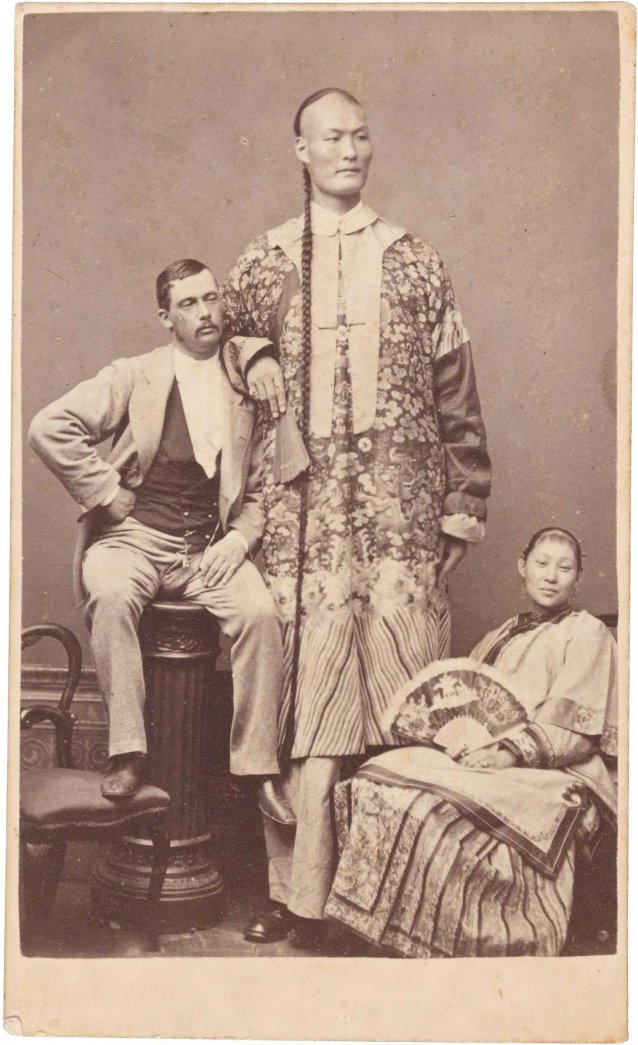

Declarations of Chang's height differ; variously described as being from seven feet eight and three-quarter inches (235.5cm) to over eight feet (240cm) tall, there are no authoritative records. He was widely believed to be the world's tallest man at the time he travelled to England, France, the United States, New Zealand and Australia with manager, Edward Parlett. He first appeared as an exhibit at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly in 1865, accompanied by his wife, Kin Foo, and a Chinese dwarf called Chung Mow. Born sometime between 1841 and 1847, he is likely to have been in his late teens or early twenties at this time and was reported in the press to be 'still growing'. He then toured Europe, where his multi-lingual capacities were much commented upon; Chang purportedly spoke between six and ten languages well. PT Barnum, the great showman and circus owner, invited Chang to America to appear in his shows for the princely sum of $500 per month, and Chang agreed, arriving for his second and final tour of the United States in 1880.

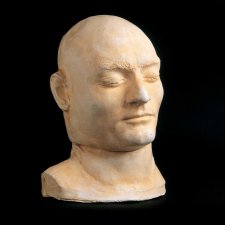

His sojourn in Australia commenced on 24 January, 1871, after the first of his American tours; it was of several years' duration and included visits and appearances throughout Victoria. He was reported to have appeared at St George’s Hall and Weston’s Opera House in Melbourne, and at the Lyceum Theatre in Bendigo where he stayed for about a month. There, he included performances for the Benevolent Asylum and contributed 50% of the box office as his charitable donation. In gratitude, the good folk of Bendigo fashioned a wax effigy of Chang which was displayed at the Easter Fair from 1877 to 1895. The touring performance also visited Echuca, Geelong and Ballarat, before travelling north on 24 April.

In Sydney, Chang was presented with a gold watch by the mayor and dined at Government House. By the time the party arrived in Sydney, Kin Foo was no longer referred to in newspapers or publicity material as Chang’s wife, but as 'a Chinese lady'. One of Chang’s multiple biographies, written in 1871, excises all references to Kin Foo as his wife that had appeared in the 1870 edition. However, as Sophie Couchman of the Chinese Museum in Melbourne argues, Chang's biographies constitute part of the publicity machine around him and, as such, are no more reliable as sources of fact than today's mass-circulation magazines in their reporting of the lives of celebrities.

It remains unclear whether Kin Foo and Chang were ever married. However, whilst in Sydney, Chang met Liverpool-born Catherine Santley; she was the daughter of a well-known publisher from Geelong and was living in Sydney as the companion to a Mrs John Rogers. Chang was introduced to Catherine (Kitty) by Mr John Rogers, who was secretary of one of his performance venues, the School of Arts Hall. A 'defined' relationship did emerge in this case; the couple were later married at the Congregational Church in Sydney, then situated in the reverend's house on the corner of College and Stanley Streets. Catherine was born in 1847, making the couple close in age. The couple had two sons and, at the end of Chang's performance career, retired to Bournemouth where they opened a tea house; Chang also imported Chinese goods into England.

Reconstructing the experience of performance requires a degree of conjecture, founded on historical accounts. Chang is first noted on the European stage at the Egyptian Hall in London during 1865-6, but really came to prominence at the great Paris Exposition of 1867. The Victorian taste for grand international exhibitions of the wonders of the industrial age is well established. Amongst the trade exhibits, however, cultural and semi-anthropological displays were also popular, feeding into audience fascination with the 'fantastic' exotica which had long been an aspect of Orientalism.

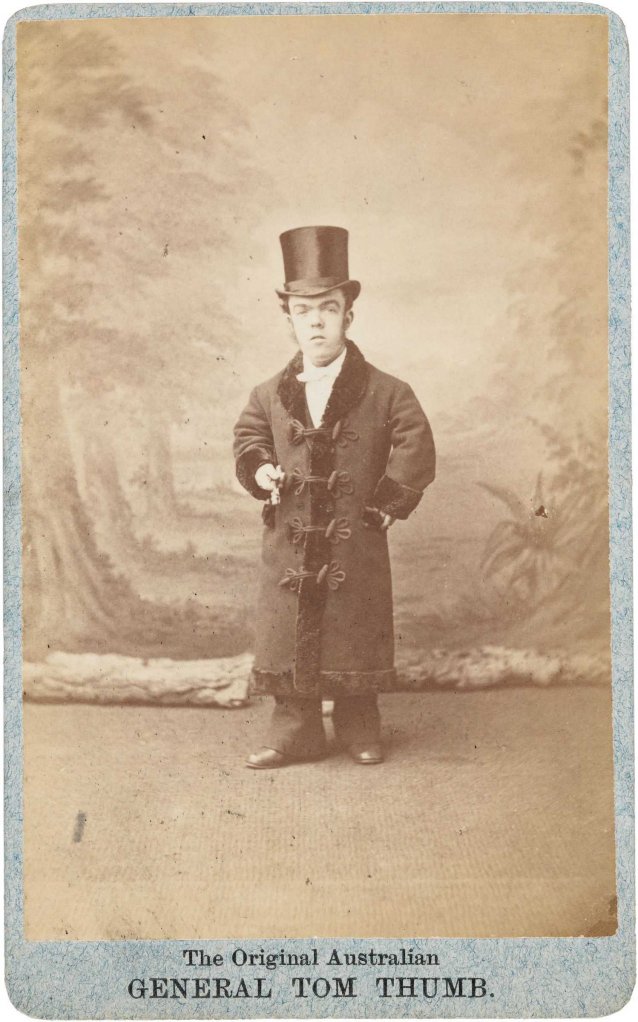

Upon evening closure of the formal exhibition halls, the surrounding gardens became a fashionable venue for entertainment until 11pm each evening. Food and drink were served and the audience wandered between outdoor pavilions and stages, marvelling at performances from tight-rope walkers, jugglers and representatives of nations of the world clad in national costume. The Chinese Pavilion was one such venue, and the wandering visitor would encounter Chang seated upon his throne or mingling with visitors to the pavilion. After the Paris Exposition, Chang journeyed to Dublin, then to Northern England and Scotland. In 1869, he spent twelve weeks at Barnum’s American Museum before touring the eastern states, and thence to California where he appeared alongside Japanese acrobats and a group described as 'a tribe of American Indians'. From San Francisco, Chang travelled to Honolulu and then to Auckland. He was a well-seasoned performer with a refined stage act by the time he reached Australia.

Surmising on the basis of a range of sources and contemporary accounts, one of Chang's Australian performances might have proceeded as follows: tickets to a levée might cost up to three shillings, with a levée in this context referring to a public court assembly at which one would attend upon a person of great rank. Amidst a hushed auditorium, a tinkle of bells would begin rising to a crescendo as a musician took to the largest brass bells with a mallet. Chang would slowly rise from his throne-like chair on stage. To the rousing accompaniment of The Great Chang Polka on the piano (supposedly written by James Marquis Chisholm for Chang's appearances at the Egyptian Hall), Chang would slowly descend to greet his audience in a ceremony referred to as 'chin chin', making light conversation and exchanging polite greetings with patrons who gasped in awe at his magnificently costumed person. His great hands would gently clasp select hands in the audience in greeting. As one Sydney Morning Herald columnist reported in 1865: ' ...judged by a Chinese standard of beauty, Chang may really be called handsome. His expression is singularly mild and gentle, almost to effeminacy. There is something very courteous and engaging, too, in his mien as he walks about from one spectator to another, shaking hands with all who desire that honour.'