It was the school project that got out of control. The task in Grade Eight was to produce a newspaper. Three years later I was still doing it, publishing Our World twice a week, running it off on my school’s Roneo machine. I always wondered what the ladies in the admin room thought as I ground the machine’s lever, each copy dropping into place, the smelly purple ink giving life to my little stories.

They say you’re blessed if you know what you want to do in life. I knew as a very young kid that I wanted to write, and I hoped to work for a newspaper. There was some writing in the blood.

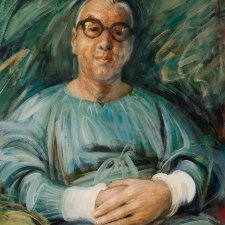

My grandmother, E.A. (Elsie) Southwell, was a writer and editor who, in the 1950s, collated a pioneering collection of pieces about the environment called Food, Soil and Civilisation, as well as editing textbooks on English expression and poetry. Grandma loved poetry more than I did. She would give me twenty cents if I learnt a poem by Keats or Tennyson. I trousered the cash but pretty quickly forgot the poem.

It wasn’t poetry that had me in its embrace. I loved journalism. What a world that would arrive at our doorstep each morning (there’s an old-fashioned idea). At age ten I would devour the words of the smart columnists on The Age, people I would come to work with later, Peter Smark, Robert Haupt, Peter Cole-Adams, Sally White and, of course, Ron ‘Curly’ Carter writing about football. I could not have imagined that in a few years I would be an eighteen year old cadet journalist at The Age, sitting next to Ron on Thursday nights, compiling the football teams for the big weekend games.

I was restless to get involved, so I took this school project further. It meant I wasn’t just a writer and editor; I was also a publisher with my own little paper. Our World reported on the goings-on in one street - Haverbrack Avenue, Malvern. It brought news of birthdays, examination successes, illness and injury, and families greetings visitors all the way from Sydney. It featured any births, deaths or marriages I could find out about. It had poems, record reviews, gardening notes (by my mother) and reflections on the worlds of sport and occasionally - and ominously for me - politics.

I was thirteen when I started the paper. I was the publisher and editor. I had a team of contributors and 'subeditors', all living in my street and all under the age of fifteen. No-one got paid (not that I had any money to pay them). It was the prestige of achieving a by-line in a boutique local publication, I suppose. So that excuse from publishers is pretty old, then. Luckily for me, everyone wanted to see their name in print, even if circulation numbers hovered around thirty-two.

Each week the pages needed to be filled, so I wrote most of the copy, and if I pleaded with the kids I was kicking the footy with, I might get a news paragraph or even a book review out of them. I also handled graphic design (well, I outlined some headlines by hand and drew some pictures).

The topics of the stories were wide-ranging, from a cat having a litter of kittens to a review of the new Simon and Garfunkel or Cat Stevens album, to a news story flagging the possibility that one of my sisters was getting engaged. (I didn’t check that one and it wasn’t true. The mood was a little bit chilly at the dining table next evening; the idea of checking and double-checking hadn’t kicked in yet).

Some weeks I didn’t have much to publish and didn’t have time to work the room, or the street in this case. Schoolwork was taking up more of my time. Some afternoons I’d lie on the floor with my little blue typewriter and an empty page in front of me, featuring just the Our World logo (which I hand-drew). Some weeks I felt like the late Joan Rivers, who once said of her forward diary (featuring a paucity of bookings) that the white was so dazzling she had to wear sunglasses.

So, consequently, some editions featured some pretty slim news stories. Under the headline 'Mrs Morrison Has A Trip', we published: 'Margaret Morrison made a visit by plane from Sydney, where she is a school teacher, to attend the races and lots of parties. This was a lovely and unexpected surprise for her family.' (Kathy from up the road filed this one).

At one stage I got entrepreneurial and walked up to the petrol station on Malvern Road and asked if they would like to take out an ad. Happily, they said yes. They gave me the copy, which I hand-wrote onto the stencil sheet, appearing as a display ad on the bottom of page one. They gave me $10. It was the only money I made from my little venture.

The production and delivery of Our World was very simple. Having 'Roneo-ed' off the copies at school, I would walk down Haverbrack Avenue on the way home and deliver it into the letterboxes.