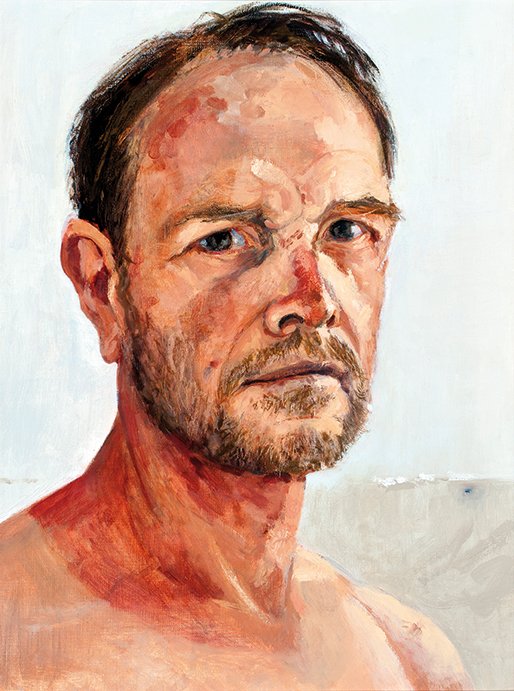

When Andrew embarked on my portrait at the start of this year, I did not know what he planned for it. Having painted his self-portrait twice, Andrew was, I thought, just looking for another subject, and I was happy to oblige because it gave us one more reason to be together. When I first went to his Melbourne studio in my usual jeans and t-shirt, and Andrew photographed and sketched me sitting in a white upholstered chair of no distinction, I did not give my appearance any thought, or what Andrew might do with the picture. I only later realised that he wanted to enter it in the Archibald Prize.

Andrew’s prime focus through the summer was his first Melbourne exhibition with Lauraine Diggins, whose entire gallery was Andrew’s to fill, so he had lots to paint. But he also gradually worked on my portrait, in which he evoked the family history I had written about in my book, Good Living Street. Andrew did so partly through the background of the painting which echoed that of Gustav Klimt’s portrait of my great grandmother Hermine Gallia, first shown at the Vienna Secession in 1903, and now in the National Gallery, London. Andrew also did so by depicting me on a dining room chair, designed by Josef Hoffmann for my great grandparents, which had only recently been acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria and, unlike the other Gallia chairs in the Gallery, was a chair on which I had never sat.

Because he was in Melbourne and I was in Canberra, Andrew picked out a photograph he took of me in his studio early in 2015, and used it to rough in my body and face and resolve the background. He also went to the National Gallery of Victoria and sketched and photographed the Hoffmann dining room chair – making drawings of the whole as well as details, supplemented by written notes. A couple of times I sat again for him on his white studio chair, even as he painted the Gallia one from the Gallery. Then, with his show at Lauraine Diggins open, my portrait became his prime focus and next goal. At the start of June, I returned for two days and sat for a long afternoon and a long morning.

It was cold in Andrew’s upstairs studio, with its window open. He was in a blue boiler suit and beanie. I had to be in my summertime jeans and t-shirt as he had reminded me to do before I flew down from Canberra. As I passed through the city on my way to Richmond, I bought a new t-shirt, exactly the same, so it would be clean and uncrumpled. At first I tried to keep my entire body still and, with just a small heater nearby, lost feeling in my feet. Eventually, I realised that Andrew was working on me bit by bit, so there was no need to be entirely still. Instead, Andrew would tell me which part, and I would focus on keeping only that in place, which was much easier. While he painted and asked questions, I tried to entertain. As usual, he wanted to know what I was writing and when I might follow his example by quitting institutional life. When late on the first afternoon we ran out of talk, he asked the painter in the studio next door for music. He offered Beethoven’s late quartets and we accepted.