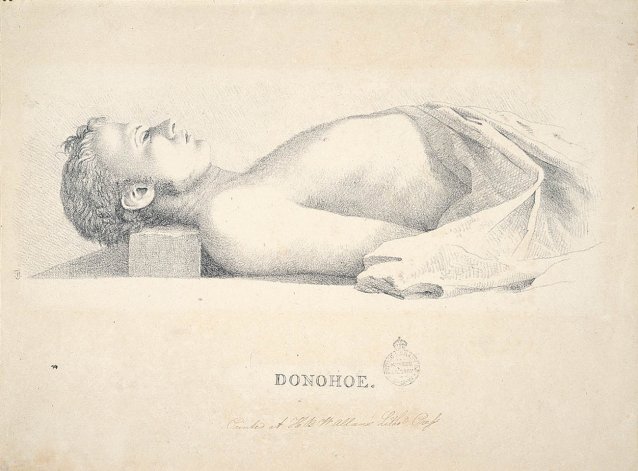

According to the caption on the lithograph issued as a souvenir of the occasion, John Jenkins was twenty-six years old when he met his death in the yard of the Sydney Gaol in November 1834. A Londoner and sailor who had arrived in Sydney in June 1833 to serve a seven year sentence for theft, Jenkins was hardly the only felon done away with in the batch of hangings that took place in Sydney late the following year, but he was possibly the only one whose execution was such a keenly anticipated event. Not only had Jenkins invited vengeance and disgust with the 'atrocity of the deed' he'd committed, the defiant and gleefully unrepentant conduct with which he greeted his trial and conviction for murder had made him the subject of outrage and fascination. Jenkins 'made such an impression on the minds of the Public', said the Sydney Herald in its account of his hanging, that at 'the time appointed for his execution, the neighbourhood of the gaol was crowded to a degree never before observed on any similar occasion, to witness the last scene of one the most depraved of the human species.'

Some months previously, around August or September 1834, Jenkins had escaped from a chain gang and taken up with two other bolters before proceeding on a series of attacks on settlers to the immediate south-west of Sydney, bailing up isolated huts and relieving their occupants of cash, clothing, food and firearms. After a few weeks on the run, he and his mates, Thomas Tattersdale and Emanuel Brace, established a hut on land that was part of the Petersham estate, a farm extending south from the Parramatta Road to the Cook's River and belonging to Robert Wardell, a barrister, co-founder of The Australian newspaper, and a close associate of some of Sydney's most powerful citizens. On 7 September 1834, in the midst of making 'a general inspection of the condition of his property', Wardell came across Jenkins and his cohorts at their shanty in the bush. Easily construing that they were runaways, Wardell engaged them in a brief exchange and tried persuading them to give themselves up, at which suggestion Jenkins shot him. Wardell’s body was found the next day.

The three offenders were apprehended in the vicinity of a pub on the Liverpool Road less than a week later, and brought before the magistrate almost immediately on a charge of wilful murder. Brace, the youngest of them, agreed to 'turn approver' against Tattersdale and Jenkins; when they came to trial the following week the court was 'crowded to excess', with spectators shocked and enthralled in equal measure by the callousness of the offence, but in particular by the contempt for proceedings and utter absence of contrition evident in its perpetrator. 'The countenance, as well as the demeanour of Jenkins, indicated him to be of a most reckless and ferocious disposition', stated the Sydney Gazette, and The Australian reported on the 'desperately audacious character' Jenkins displayed in physically attacking his co-accused in court. On being found guilty and sentenced to death, Jenkins said that 'they might have well have sent him a bloody old woman as the counsel he had... that he had not had a fair trial, but that he did not care a damn for anyone in the court; and that he would as soon shoot any of the persons present as not'.

Violent, shameless, rancorous, murderous: Jenkins was exactly the type of individual whose likeness was ripe for commercial exploitation, and his activities, happily for Sydney's small but mercantile-minded artist community, coincided with the emergence of the local printmaking industry and the development of a market for depictions of peculiarly colonial subjects. As historians of Australian colonial art have often explained, the 1830s was the decade during which locally-based artists and printers began being able to capitalise on the numbers of free settlers encouraged to the colony during the previous decade, transforming Sydney and Hobart from brutish outposts into thriving and respectable municipalities replete with the usual commercial features of British provincial centres. 'The muses and graces are not inimical to our southern climes', wrote Presbyterian minister John McGarvie in 1829; 'there are several good painters and engravers in Sydney, and bank plates, shop bills, silver plate arms, lettering, cards & c. and all that is technically named job work may be executed here with as much beauty and accuracy as in any provincial town in Britain.'

The transportation system having already supplied the Australian colonies with a number of proficient printmakers, the increased free immigration of the twenties and thirties bolstered the available numbers of artists versed in the 'useful rather than the ornamental' branches of the profession, and those who chose to come to Australia for the economic opportunities afforded by middle-class, consumerist communities. This meant a setting that was no longer primarily concerned with the production of natural history, ethnographic and topographical images that served a curiosity or propaganda purpose and were intended solely for the satisfaction of interests and authorities at 'home', but, rather, one that had local consumers and collectors in its sights with the types of images that reflected colonial quirks and experience.

As colonial art scholar Richard Neville has explained, the printing industry in pre-1850 Sydney was 'competent but limited', unable to equal the technical quality of works produced in London, and making few pretensions to 'high art', but sufficiently equipped to create 'provincial imagery... for a market which did not require highly finished works of art.' In communities with such a history of malefaction to draw on, it is perhaps to be expected that the depiction of various types of ne'er-do-well forms a small but distinct vein in the output of certain artists working in Australia in the first half of the nineteenth century, and whose works constitute an Australian edition of the catchpenny criminal images and execution broadsides that had been a feature of the English popular print trade since the early 1700s.