Avedon’s significance to the history of photography, however, has more to do with the backgrounds of his images than with the personalities that occupy the frame. Or, to put this more precisely, Avedon’s artistry is revealed in the ways he situates his subjects in the pictorial space of photography. This is most clearly demonstrated in his critically acclaimed series In the American West, where decidedly un-famous and earthy people have been extracted from the landscape of America’s mythic frontier to become cyphers of the human condition itself.

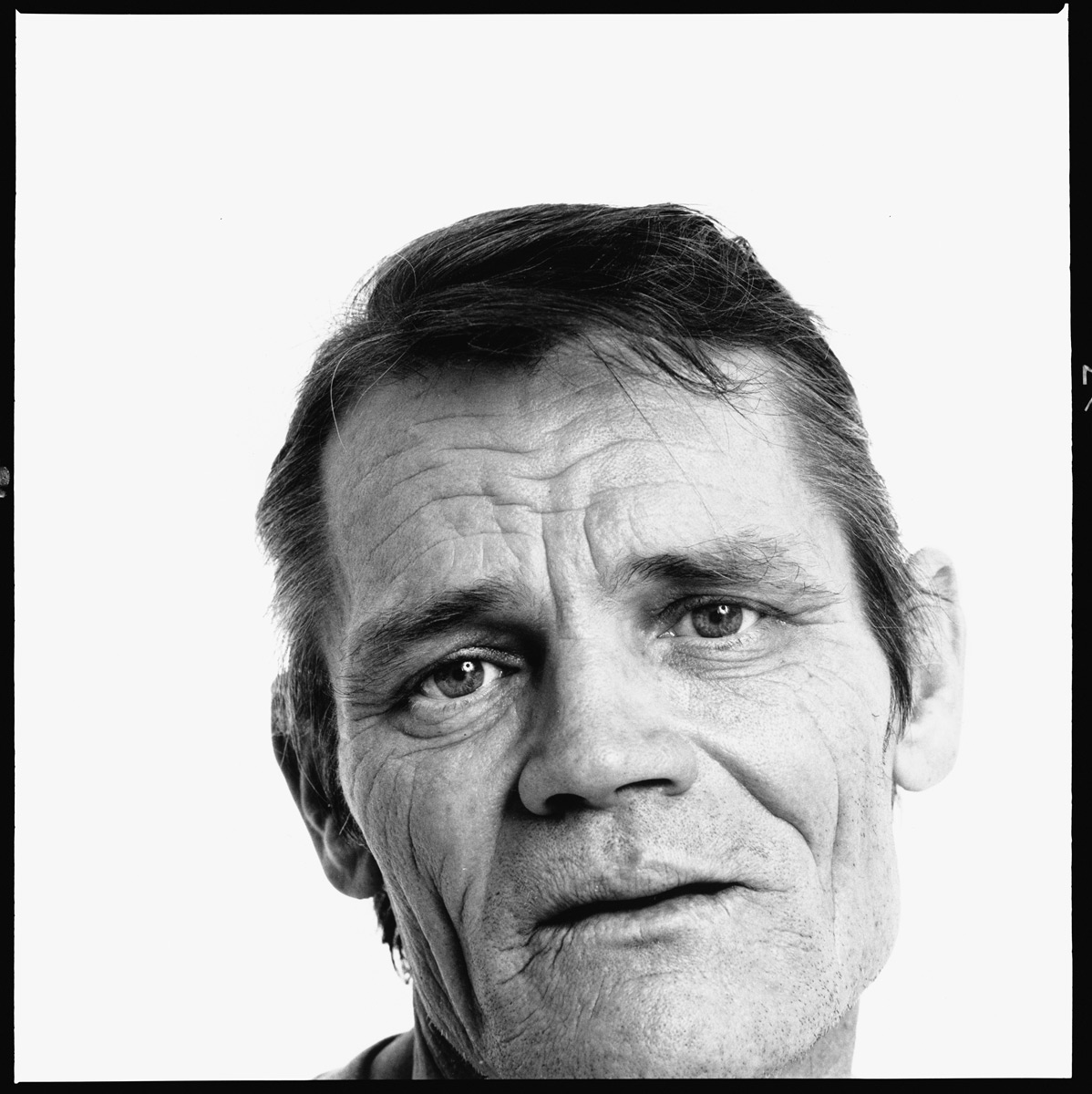

Like most of Avedon’s mature work, the 124 portraits that comprise the In the American West portfolio have been shot against a backdrop of white paper. The lighting is uniform, with no dramatic highlights or shadows, so the background offers absolutely no sense of visual depth or physical place. In contrast, the figures that float in front of these white voids have been recorded with relentless specificity. Using a large-format camera, Avendon captures the subtle signs of wear and tear that locate a body in its life. Sweat-stained shirts and the sun-kissed faces ground these portraits in the materiality of their existence.

The black edges that frame these images contribute to the push and pull of the pictorial space constructed by Avedon. Printing the edge of the negative is a significant convention in the history of film-based photography because it insists on the documentary integrity of the image. The black edge of the original film frame indicates that the picture has not been cropped or manipulated. And Avedon often emphasises the ‘honesty’ of the black edge by allowing his figures to slouch off centre or butt their head against the frame. What we see in the photograph is exactly what was captured on the film when it was exposed to the world through the camera’s lens.

Avedon’s artistry lies in his articulation of these three elements: the white void of the background, the gritty fidelity of the figure and the veracity of the black frame. He uses these compositional elements to insist on the physicality of the photographic object itself, but also to emphasise the physicality of the life forms that he photographs. In doing this, Avedon asks us to recognise individuals as vulnerable actors in a profoundly material universe. But the edgy disjunctions between the different elements also works against any organic or holistic conception of our physical reality; life is haunted by existential ruptures and uncertainties.

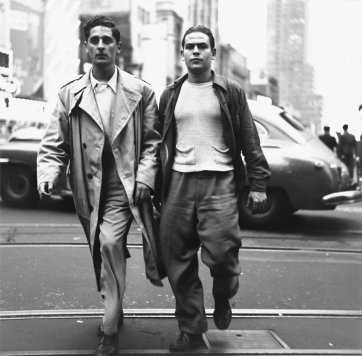

The photographs selected by Christopher Chapman for this exhibition allow audiences to appreciate the development of Avedon’s artistic vision. Long before Avedon made a practice of using white backdrops, he found other ways to create edgy figure/ground relationships. In his early street photography, for instance, figures often seem frozen while the city around them rushes away along diagonal lines. Conversely, sometimes the figures are agitated with motion blur while the street holds fast. And we can see the white backdrops anticipated in the way Avedon frames subjects against empty expanses of water, snow, sky or pavement.

The inclusion of commercial signage and newspaper headlines in Avedon’s street photography is also of interest because of the way he uses it to fragment the field of vision. This compositional device is employed with sober effect in the images of people holding up newspapers that announce President Kennedy’s assassination. The flat graphic quality of the type merges with the surface of the photograph and pushes the figures backwards into the grey tones of the photograph. There is a disconcerting sense of alienation in these images; the world has become unhinged.

Avedon’s capacity for disrupting the unity of the photograph is also the thing that makes his portraits of avant-garde artists and political activists so engaging. Contrary to the convention of photographing artists in the habitat of their studio, or ‘at home’ with the instruments of their craft, in Avedon’s work they stand alone. Abstracted into edgy white space, they become forces of pure creativity that seem to unsettle the image with their very presence. Avedon is similarly able to frame political activists as personifications of imminent change within the formal instability of his photographs.

Even in Avedon’s work for fashion houses and glamour magazines we can see his distinctive style being elaborated. The iconic Harper’s Bazaar image Dovima with elephants, evening dress by Dior, Cirque d'Hiver, Paris, August 1955 makes it clear that Avedon pursued his formal concerns throughout his photographic practice, across a range of genres. In this instance, he has effected a dreamy disjunction between the American fashion model Dovima and a troupe of circus elephants. Dovima shares the same straw-strewn concrete enclosure as the animals but her graceful figure, sheathed in a sleek black and white evening dress, has an incommensurate relationship with the lumbering forms of wrinkled grey elephant hide.

It has to be said that there is something very ‘American’ about Avedon’s artistic vision, with its focus on the individual as a pioneer set adrift in a material world; but this existential theme certainly has resonance further afield. In order to gain a fuller appreciations of Avedon’s work from an Australian perspective it is informative to consider local photographers who have used portraiture to explore the human condition with similar visual devices.

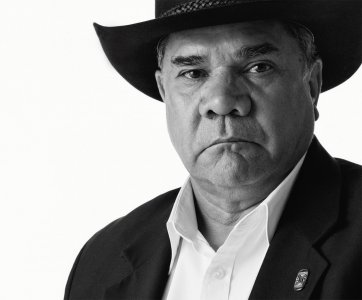

The Tasmanian-based Aboriginal photographer, Ricky Maynard, offers a particularly useful point of comparison because, like Avedon, he uses a large-format camera and often frames his subjects against a stark white background. The effect is similar to Avedon’s, in that this format brings a certain physical gravitas and material specificity to the figure. Maynard’s stated ambition, however, is to pay tribute to the nobility and indomitable spirit of Indigenous people. Consequently, he doesn’t share Avedon’s interest in unsettling his subjects with a sense of uncertainty. Quite to the contrary, there is an abiding air of stillness in Maynard’s portraits. He achieves this by dropping the camera’s point of view below the subject’s eye line, so that the background becomes an over-exposed sky and the figure remains grounded in the world; in touch with their land.

An Australian artist who does share Avedon’s interest in existential crises is the Melbourne-based photographer Rod McNicol. For over three decades McNicol has been inviting people into his studio to stare down the lens of his camera while he cites Susan Sontag saying that all photographs are memento mori. Like Avedon, McNicol uses uniform lighting and monochrome backdrops to isolate his sitters and foreground their physical vulnerability. These matter-of-fact portraits, which are shot with relentless uniformity, function as witnesses to the inescapable passing of time.

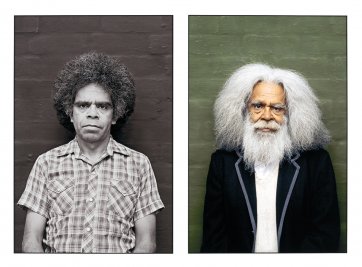

McNicol has also made a practice of returning to re-photograph some of his subjects, creating diptychs that juxtapose older and younger selves on the same backgrounds. The two portraits, placed side by side, metaphorically unhinge the subject from itself. This is similar to the ontological ruptures that Avedon affects in his composite murals of Allen Ginsberg’s family and Andy Warhol’s Factory, by doubling and repeating individual figures within the group portraits.

Weaving different durations of time through the stillness of a documentary photograph is something that Jon Rhodes has been exploring since the late 1970s. Based in New South Wales, but regularly living with Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory and Western Australia, Rhodes’s perspective on Indigenous culture is invested with a poetic sense of existential vulnerability.

Like Avedon, Rhodes prints the black frame of the negative to underscore the veracity of his black-and-white photographs. In Rhodes’s hands, this device also functions as a window to suggest that he is offering just one point of view on a complicated world; one instant among many durations.

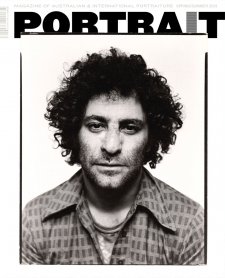

The work of Richard Avedon is perhaps most readily associated with intimate images of very famous people. These portraits of 20th century superstars are well known because they resist the idealisation of celebrity and reveal the humanness of revered individuals. Capturing their physical anomalies, their idiosyncratic gestures and their unguarded moments with a shameless clarity, Avedon fosters a sense of familiarity with the famous. And we love this candour in the same way that we enjoy referring to these people who we’ve never met by their first names: Marilyn, Andy, Twiggy; John, Paul, George and Ringo.

In the same way that backgrounds and figures seem to move at different speeds in Avedon’s street photography, Rhodes also likes to mix different rhythms within a single still. Flags flap whimsically in front of landscapes that endure. Sacred Aboriginal trees stand stoically amid the motion blur of passing traffic. In Rhodes' portrait of the Western Desert painter John Tjakamarra, the artist is caught mid-stride, emerging from the scubby landscape; the purposeful vitality of a contemporary Aboriginal man juxtaposed with the slow, almost imperceptible transitions of the natural environment.

As contemporary photographers increasingly embrace digital technologies, the formal qualities that defined the visual language of film-based photographers in the late 20th century have become more apparent. Avedon is a master of this milieu, and his astutely constructed pictorial spaces provide valuable insights on the expressive potential of the photographic medium during that period. This exhibition offers audiences the opportunity to appreciate the elegance of Avedon’s style, but it is also a chance to let his artistic acumen illuminate our understanding of photography more generally.