If you Google artist Tracey Moffatt, chances are that within the top ten results will be a reference to her now iconic 1989 work, Something more. A series of nine photographs – six in saturated colour and three in black and white – Something more presents an unsettling narrative about a young woman’s attempted escape to the big city from the dire realities of existence in a tin-pot place populated by stereotyped characters: a boozing oaf; a bored, trashy slattern; a sensitive Asian youth; a pair of niggling, barefooted imps.

Moffatt herself plays the leading role of the woman whose stab at something more ends with her dumped face-down on a highway, 300 miles from the metropolis. Like many of Moffatt’s subsequent works, it is dreamlike and disjointed, and rippled with intimations of violence and menace. It is generally considered the work by which Moffatt staked an irresistible and unshakeable claim on the art world’s attention, representing the shift from her earlier, more documentary-style work of the mid-1980s to the highly-constructed and stylistically diverse works in photography and film that have since earned her worldwide acclaim. Almost a quarter of a century after its creation, Something more remains perhaps the best-known example of Moffatt’s work and is cited as exemplary for its lurid, cinematic quality and overt fakery; for the tempering of its gloss with darkness; and for its subtexts on matters like racism, gender, fantasy, cruelty and sources of personal damage. Something more set the tone also for much of Moffatt’s work in its manner of tapping into our collective memory – of crappy soap operas, corny sitcoms, pulp magazines, comic strips and matinee movies – so as to make observations about subjects like identity and history, and what it is to be human.

One of Australia’s most successful and internationally visible contemporary artists, Moffatt was born in Brisbane in 1960 and studied Visual Communications at the Queensland College of Art. Of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal heritage, Moffatt and her siblings were raised in otherwise average circumstances in a foster home in the suburb of Mount Gravatt, factors that Moffatt has since cited as catalysts for her work and career. ‘If I had been from a well-to-do family, I would have immediately been sent off to join a children’s theatre group … or sent away on an art camp for gifted children’, Moffatt stated in an interview in 2003. Instead, the unremarkable or even straitened nature of her surroundings meant ‘a longing I must have had to want to escape reality and make my own worlds. It was rare that distractions were provided. We had to make our own fun. There was television and there were books. Ideas came from these’. Moffatt’s first photographs, she has said, arose out of this wish to occupy other, imagined scenarios. ‘At an early age I realised I wasn’t good at painting or drawing’, Moffatt has said, ‘but I liked creating make-believe, inspired by other fictions in film and novels. I would walk around singing and acting out roles. I would make kids dress up then take a picture of the event – it seemed the next simple step’.

Quoted as stating ‘I am not concerned with capturing reality, I am concerned with creating it myself’, Moffatt has since perfected the exploration of the camera’s capacity for artifice, her great and sometimes wicked skill in manufacturing ‘truths’, appropriating pop culture modes and in mimicking historic, outmoded or seldom-used photographic processes and styles has seen her heralded as a leading exponent of postmodernism. Someone who ‘makes rather than takes pictures’, as photography curator Gael Newton has explained, the situations in which Moffatt’s works are created are more akin to film shoots than sittings: ‘Technically, I’m quite stupid. I hardly know how to use a camera’, Moffatt says. ‘I often use technicians when I make my pictures. I more or less direct them. I stand back and call the shots’. Although her work resists definition in terms of a specific visual or technical ‘style’, it is characterised by a strong and distinct synthetic sensibility that, for all of its deft and celebrated toying with reality, resonates in spite of itself, retaining grains of truth about personal history and experience. As curators Daniel Palmer and Blair French have observed, Moffatt’s are ‘images full of artifice that ultimately present real and important subjects’. Consequently, threading through Moffatt’s output also is a consistent vein of autobiography and portraiture. Not the sort of portraits that are straight or truthful transcriptions of their subjects, but those that in their highly constructed, knowing and manipulated scenarios offer vivid, complex and clever examinations of self, memory and identity, and that combine fiction, performance and fact in equal measure.

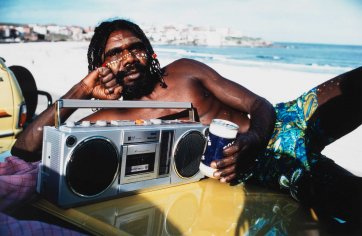

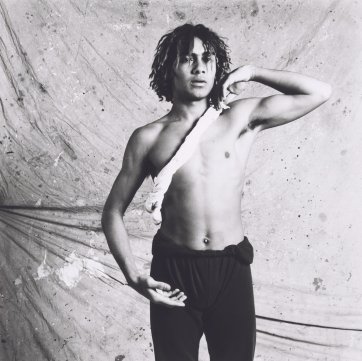

Moffatt’s first exhibited works were portraits. One of a notable group of artists whose work introduced a new, potent direction for contemporary Australian art and the representation of the experience of Aboriginal people, Moffatt moved to Sydney from Brisbane in the early 1980s, working initially in photography, documentarymaking and film. In 1986, examples of her photographs – The movie star and Some lads – were included in a landmark Sydney group exhibition of the work of Indigenous photographers, NADOC ’86. Moffatt’s contemporary and fellow-exhibiter, Michael Riley, stated that the exhibition’s power resided in it being an instance wherein Indigenous artists ‘were dictating what they wanted to show, and how they wanted to show images of their own people, rather than ethnographic photographs by missionaries as a curiosity or something … the ‘dying race’ sort of thing’. The movie star 1985 is a glossy, subversive depiction of actor David Gulpilil. It exemplifies Moffatt’s work, drawing unashamedly on the language of advertising and 1980s shrimp-on-the-barbie-style tourism campaigns yet at the same time wittily knee-capping it, while also making reference to Australia’s colonial past and the dispossession of Aboriginal people. The photograph’s subject, his nose and cheeks dotted with traditional patterns rather than zinc cream, is shown reclining on a polished car bonnet: boom box in the foreground, beach in the background, tinny of Fosters in hand. Some lads is a series of five photographs of dancers from the National Aboriginal and Islander Dance Theatre. As with her portrait of Gulpilil, the series was created in reaction to the practice – perfected in the 19thcentury studios of photographers like JW Lindt and Henry King – of photographing Aboriginal people as mute, stiffly-posed curiosities. In further proof of her agility in twisting and undermining established modes of depiction, the sitters in Some lads reject the exploitation and intrusion enshrined in those earlier photographs. As Moffatt said in 1987: ‘I encourage my subjects to enjoy the staring camera … to intentionally pose and show off. In an attempt to dispense with the seriousness and preciousness, it captures a lyricism and a barely assigned bold sensuality’. Her 1987 short film Nice coloured girls similarly dismantled the habit of representing Aboriginal people as powerless, following three young women on a night out in Kings Cross funded through their manipulation of a soused white chump.

Then, in 1989, came Something more, representing what is considered the point at which Moffatt’s work became, as explained in the catalogue for her 2003 retrospective exhibition at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art, ‘more concerned with staging, with constructing images rather than telling a straightforward tale’. Employing key elements of her work – the unashamedly ersatz painted backdrops along the lines of those seen in Nice coloured girls and the 1989 short film Night cries, for instance – the nine images in the Something more series revel in their own tawdriness, moving the viewer, storyboard-style, from the hopeful technicolour opening scene through disjointed vignettes to the story’s grim monochrome conclusion. Subsequent works, such as the two instalments of Scarred for life (1994 and 2000) – in which damaging childhood incidents and secrets, told to Moffatt by friends, are reconfigured as cheap, captioned magazine illustrations – utilised the same method of combining truth and fiction, underlining the artist’s dexterity in ‘creating reality’ and in fashioning an incisive, palpable sense of identity and lived experience from that which is artificial, ephemeral and imagined. Something more, as the artist sees it, ‘is in a sense autobiographical. It’s about escape and dreaming of better things’. By virtue of being so directed and ‘faked,’ it is also perhaps among the most striking examples of contemporary self portraiture and a brilliantly successful and effective recast of the genre’s conventions and traditions.

Despite, in one interview in 2001, expressing a limited interest in the self portrait – ‘I just couldn't be bothered doing it and I prefer to work with other people’, Moffatt said – the idea of it has figured strongly in much of her work and has done so in some of her most distinctive and compelling images. Firstly, there are ‘self portraits’ in the manner of the three images forming Backyard series 1998, the artfully grainy and discoloured, amusing, but also melancholic and unsettling restagings of instances, retrieved from family photo albums, where she ‘made kids dress up’ and then photographed them. In part about a specific moment or recollection, images such as Nativity scene 1974 from Backyard series might also be read as a reference to the experience of Moffatt and her siblings as Aboriginal children growing up within a white foster family. Likewise, I made a camera (2003) – described by the artist as ‘a picture about childhood creativity’ – recreates the occasion when, as an eight-year-old and in emulation of a scene from a Charlie Chaplin movie, she pretended to take photos with a cardboard box. Then there are the works that are more obviously in the self portrait mode, such as the forty images wherein Moffatt adopts the symbols and gestures of famous women born, as she was, Under the sign of Scorpio 2005. Often using clothes and props from her own wardrobe, Moffatt turned herself into people like Georgia O’Keeffe, Hillary Clinton, Oodgeroo Noonuccal, Marie Curie and Indira Ghandi in an attempt at finding out ‘what makes the Scorpio tick’. In 2008, Moffatt produced the brilliant First jobs, a series of twelve images wherein she grafted her smiling, white-toothed likeness into sunshiny, government propaganda-style pictures – a pineapple cannery, a starched motel dining room, a cafeteria counter, a suburban hairdressing salon, a fruit shop with perfectly arranged tiers of polished produce – approximating the part-time jobs she had as a student, the brightness and order of the images belying the dull, dead-end or even exploitative nature of the jobs depicted.

As with Something more, both Under the sign of Scorpio and First jobs are instances wherein the artist muddies the distinction between artifice and self, making adroit, sportive use of the presumed connection of photography to truth and the place within portraiture of pretence – of putting on a particular face. Just as I made a camera was a manufactured image of Moffatt ‘playing at being a photographer’, her famous 1999 Self portrait shows her acting the part of the bold, Pentax-wielding glamourpuss lady photographer, attired safaristyle and posed against a faux desert backdrop. Recently acquired for the National Portrait Gallery’s collection is a one-off, alternative self portrait. A diptych, it’s composed of a black and white print from the 1999 Self portrait shoot alongside a handcoloured print of the same image, produced in New York in 2005.

Moffatt has written onto the black and white shot her directions for the retouching of its companion: ‘fix arm fat & under arm hair’, ‘whiter eyeball’ and ‘lips a little fuller’. Like The movie star and Some lads, it’s another astute and nifty reworking of custom, this time playing with self portraiture’s function as a method of showing off, and of revealing a certain side of one’s personality. Laying utterly bare the artist’s established and gladly professed relish for concocting reality – ‘you can click a button and make yourself look like a movie star’ as she once said of Photoshop – Tracey Moffatt’s cracking Self portrait is all the richer and possibly more exemplary for being so blatant about the elements of make-believe and contrivance that have consistently characterised and distinguished her work. It’s a self portrait in maybe the truest, most satisfying sense of the term, being one wherein artistic sensibility and sitter are one and the same thing.