One morning in St Petersburg, Collegiate Assessor Kovalyov, who also liked to be addressed as Major Kovalyov, awoke to find his nose missing. He was the key protagonist in Nikolai Gogol’s short story The Nose [Hoc] of 1836. Freed from the face of Kovalyov, the Nose soon acquired the rank of State Councillor and dressed appropriately in a grand goldbraided uniform with a stand-up collar, buckskin breaches, cockaded hat and a cloak the colour of the horses that pulled its carriage.

In its elevated new role the Nose now outranked its owner and considered Kovalyov unworthy of its attention and so ignored him; preferring to parade in its carriage through the streets. On spying the Nose, Kovalyov wondered to himself, how he could approach his Nose, given its now grandiose demeanor and high rank as a State Councillor.

This story was a perfect vehicle for Gogol to satirise Tsarist Russia of the 1830s – a time of despotism, terror, great bureaucracy and social stratification. For contemporary South African born artist, William Kentridge, Gogol’s fable was equally perfect in an exploration of his country’s recent history: ‘In The Nose, you’re very aware of it being about a hierarchy in Russian society, a hierarchy of bureaucrats but also a hierarchy of the world; the Tsar, the patriarchs, the aristocracy, peasants, Jews and Muslims, animals, plants, and stones. And there’s a kind of absurdity in that. That rings a bell with anyone from South Africa, where we had a kind of crazy hierarchy also, our own great chain of being, until apartheid ended, with whites, and then below whites, Asians. Then there would have been Indians, then mixed-race people who were classified as coloureds, and below that, Africans.’

In 2006 Kentridge produced a radical opera of The Nose composed by the young Russian born Dmitri Shostakovich in 1928. This was a time when, according Kentridge, ‘all music seemed possible’. The Russian musician’s opera unfortunately was only presented as a concert and to bad reviews, including official government newspaper Pravda, where his work was criticised for being a ‘muddle not music’.

A confused identity

Subsequently and over a three year period, Kentridge created a series of thirty intaglio prints inspired by Gogol’s tale. In this portfolio, Nose, the artist experiments and extends the notion of what is a portrait. Adopting the aesthetic of both late 19th century and Russian avant-garde art and Constructivism of the 20th century, Kentridge portrayed the Nose wandering past famous scenes by Edouard Manet, Edgar Degas and Pablo Picasso, which somehow magically appear in the streets of the city. The figure of the legendary Russian ballerina, Anna Pavlova, whimsically sports a nose as she effortlessly floats across the stage in a fluffy tutu. Adding to the absurdity of Kentridge’s pictorial tale, the Nose also appears strolling past a model of that great monument to the Third International designed by the Russian Constructivist Vladimir Tatlin (which was intended to rival the Eiffel tower, but never built); imperiously riding a horse; disdainfully meeting its nose-less owner Kovalyov, or ascending the stairs of El Lizitsky’s avant-garde design for Lenin’s podium, where the Nose almost regally follows that great Bolshevik orator’s footsteps, as Kentridge would have him climb the social ladder.

According to Kentridge, when considering the content of The Nose: ‘There are two themes that we follow in the story that are in the opera. The one is the theme – one theme which Gogol is writing about is the terror of hierarchy. And the other theme, of course, is a person divided.’ Themes of hierarchy and confused identity pervade Kentridge’s portfolio. Kentridge depicts the Nose setting forth through the Tsarist capital. He places the Nose on a horse – a fitting accompaniment to such an esteemed figure with ‘airs and civic ambitions’, according to Kentridge, who observes: ‘A horse is exactly the right scale for the magnification of a man, for making him magnificent. A man on a chair or at a table is ridiculous. On a pedestal we begin to let him grow. But put the man on a horse — and preferably a horse on a pedestal — and you have a hero or a tyrant, at any rate someone who has made a name for himself. A horse fits so snugly under the legs. It feels not just connected to a person, but part of him, an extension of him to show who he really is.’

For Kentridge placing the Nose on a pedestal was equally grand. Gogol himself had a notable aquiline nose and a portrait bust of the 19th century writer is housed at the Hermitage. But Kentridge chose another style for his Nose, which he describes as an ‘Ashkenazi Jewish Baltic nose’. This Kentridge placed on a bust of a Russian nobleman he also viewed at the Hermitage – creating a grand vision of great splendour and exalted status in Gogol’s tale of dictatorial Tsarist Russia.

A rogues gallery

In this suite, Kentridge also alludes to more recent history – the era of Shostakovich in the early years after the Bolshevik revolution and the subsequent rise to power of Joseph Stalin in the USSR. Stalin had been grossly underestimated by many including by the Premier of the Soviet Union Vladimir Lenin, who criticised him for being ‘bureaucratic’ and steeped in ‘serf culture’. Leon Trotsky too failed to comprehend Stalin’s character, choosing to describe him as a ‘dull mediocrity’, to his own great cost. Following Lenin’s death in 1924, Stalin built a power base by developing an almost religious cult of Lenin, in an attempt to inherit his mantle. Stalin’s growing dictatorial rule was consolidated at first by the establishment of labour camps, followed by the Show Trials of the 1930s, which created a society permeated with fear and retribution.

Drawing an analogy with Gogol’s era, Stalinist Russia, and the recent era of apartheid South Africa, Kentridge composed his pictorial version with a mug shot – an Official Police Portrait of the Nose as it was brought into custody. Though Shostakovich anticipated his own personal demise due to the growing public hostility of the politically powerful towards his work, the composer was never arrested. Others were not so lucky. Kentridge alludes to the fate of another radical in the performing arts, theatrical director Vsevolod Meyerhold. In his double portrait – both frontal and in profile – Meyerhold is paraded before a screen at a police station registering his height, as well as his physiognomy. As with any such portrayal of a mug shot, a suspect in this ‘Rogues Gallery’, by inference is guilty. Meyerhold’s identity acquires criminality by the style, format and location and he is portrayed by Kentridge as a mask – a nose. His guilt is further emphasised by the sign around his neck indicating he was a liar. His fate is certain and this unfortunate avant-garde theatrical producer was arrested in 1939 and shot after he had ‘confessed’ the following year.

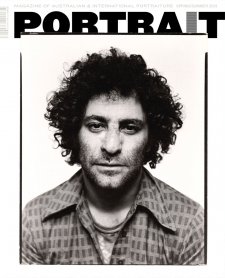

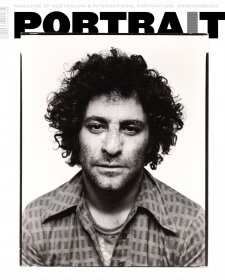

The theme of the Great Stalinist Purges continues in the Kentridge series with the artist’s mug shots of further Soviet political figures found guilty in the Show Trials. Initially Grigory Zinoviev, a devotee of Lenin, sided with Stalin to destroy Trotsky. He was then arrested in December 1934 and two years later put on trial for treason as one of sixteen ‘Old Bolsheviks’. Trotsky had been ‘airbrushed’ out of photographs of himself and Lenin. Images of other political figures who earned the wrath of Stalin were not totally erased from the pictorial history of the Soviet Union. Kentridge’s portrayal of the meek Zinoviev was based on a photograph of a curly headed almost boyish figure. For his etching, Kentridge papers over Zinoviev’s nose, implying that he too is nose-less – that he is politically impotent. His fate is confirmed by the sign around his neck, ’Senseless requests’ – evoking the brutal idiocy of the ruthless regime which now destroyed him. He too had foolishly underestimated Stalin. Portraits in Kentridge’s ‘Rogues Gallery’ continue with the figure of Zinoviev’s braver compatriot Lev Kamenev – another follower of Lenin – whose opposition to Stalin in the 1920s and overstated links with Trotsky led to his demise during the Great Purges and was also charged in the Show Trials. Unlike his associate Zinoviev, the more courageous Kamenev did not buckle as he faced certain death. Inspired by a photograph of this ‘Old Bolshevik’, Kentridge characterises Kamenev as a mature bearded man, his eyes and nose are not shown – covered by the absurdist legend ‘Asleep’. Again his noseless features suggest Kamenev’s political helplessness, while highlighting the grotesque nature of his fate.

Faceless men

Others who were part of the Central Committee of the USSR survived the Great Purges and also appear in Kentridge’s line-up. Vyacheslav Molotov, for instance, was adept in pleasing his political patron Stalin and was one of the original faceless men of politics. Molotov’s characterless appearance is emphasised by Kentridge with an empty circle for his face with the addition of the number ‘1’ in the artist’s portrait. Thus Stalin’s right-hand-man was perceived as a bland, featureless bureaucrat by many. Molotov outwardly developed a thoroughly colourless non-descript personality, which belied his own cunning ambition and ruthless quest for power. He implemented Stalin’s disastrous collectivisation of the farms, which led to large scale famine, bringing hunger, deportation or death to millions. During the altercations between the USSR and Finland, the Finns applied his surname to a cheap incendiary device, the ironically titled Molotov cocktail, much to his distaste. Despite Molotov’s active involvement in the Purges and policy failures both within the USSR and abroad, he was to die of old age. Kentridge also created another one of his faceless men within the Central Committee of the USSR with his portrait of Mikhail Kalinin – a man known to love the company of ballerinas. A Bolshevik revolutionary, like others appearing in this portrait series, Kalinin survived the Purges, as Stalin’s loyal political ally. Like Molotov, he was adept at remaining behind the scenes although, unlike Molotov he was notable for doing very little – maybe this is why the artist chose to depict him as empty headed with a red circle, created in the style of an early 20th century avant-garde aesthetic, which Kentridge so admires. Kalinin’s loyalty, despite the imprisonment of his wife, is made evident by Kentridge awarding his sitter a Lenin badge of honour.

The power of nonsense

In this series of portrayals in Nose, Kentridge has married the nonsensical and bureaucratic tyranny of Gogol’s Tsarist Russia, with that of Stalin and the recent damaging history of his own homeland. He has done so in a jocular, absurdist manner which belies the great tragedy of a rule that is both surreal and despotic.