Contemplating the breadth and depth of subject matter in art making by Indigenous practitioners across the country, the genre of portraiture does not automatically leap to mind. This is mainly due to the broader Australian public’s conceptualisation of Aboriginal art (the term commonly utilised in the commercial fine art sector), which is informed by the omnipresent, largely abstract painting from remote communities.

This phenomenon, described by the provocative Queensland Indigenous collective ProppaNow as the ‘oogabooga’ effect, is an ongoing bugbear for urban-based contemporary practitioners, many of whom opine about the struggle to have their work’s authority as Aboriginal art realised in the collective consciousness of the Australian and international fine art arenas. Trends on the local commercial fine art market corroborate this urban/ remote dichotomy, but this is not apparent in Australian public institutions, where support for the work of urban based contemporary practitioners in Indigenous art collections (and contemporary collections) is strong. The other main factor influencing the reception and acceptance of portraiture within Indigenous art practice is how we look at/see/think about art. The non-Indigenous public, in the main, is wholly influenced by the Western art historical canon, whether they are trained or not. Just as First Contact apocrypha tells of Aboriginal people not seeing Cook’s ship because it was unimaginable, the painting of self as an interconnected feature of country in work from remote communities is not recognisable as portraiture. This says more, however, about the broader understanding of Indigenous culture and the privileging of western historical norms than it does about individual capacity for perception.

The great Utopia artist Emily Kame Kngwarreye often explained that her paintings were about ‘the whole lot’, meaning that her existence and her country were inseparable, and this was always represented in her work, irrespective of its style. Indigenous artists Australia wide demonstrate this concept of self in paintings of home/country. The late Yulparija artist Weaver Jack, for example, resided in the Bidyadanga community near Broome, far away from her traditional country Lungarung, in the Great Sandy Desert. Commenting on her Lungarung paintings, she said: ‘This is me, this is mine, the whole lot is me … he is always here (clasping her heart). We are same one. My country is me.’ The mark Jack used to represent herself in her works, seen variously as an ‘x’ or ‘t’, carries figurative resonance and is, in most cases, almost indistinguishable from the many lines she used to form the features of her country. In 2006, Weaver Jack in Lungarung was selected as a finalist in the Archibald Prize for portraiture. Framed against the rigours and rules of the western art canon, this would have been unacceptable, but in the Indigenous art-land-law-identity nexus, the collapsing of boundaries such as these is the norm. The inclusion of Weaver Jack’s portrait of her birth country in the Prize is testament to a more mature critical understanding of Aboriginal contemporary art at work in the establishment.

This identification is also apparent in Jan Billycan’s amorphous, visceral paintings of country. Usually titled Kirriwirri, they depict her father’s country and, by default, her people: ‘Our clan is also named Kirriwirri, and call each individual members of this clan Kirriwirri.’ In the 2007 National Gallery of Australia’s exhibition Culture Warriors: National Indigenous Art Triennial, Patrick Hutchings confirms that this country/self connection is innate to Billycan and inherent in all her work. ‘She paints both the land and the human body, itself an extension of the land … A living waterhole becomes a liver or kidney, while the tali (sand dunes) are stretched across the canvas like the human ribcage.’ The conceptual divide about the Indigenous artland- law-identity nexus in Australia is slowly being bridged. Overseas, the chasm still looms large, but in the pioneering city of Seattle, Washington, one public institution has taken an idiomatic leap of faith across this gulf to actively engage its audiences with more difficult conceptual frameworks.

In Ancestral Modern, the 2012 exhibition of Aboriginal works of art from the collection of Margaret Levi and Robert Kaplan, the Seattle Art Museum (SAM) abandoned the easy path of pitching the show in terms of another Dreamings, the famous 1988 New York exhibition that cemented ideas about Aboriginal art in the American consciousness. Staged twelve years either side of the millennium, the titles of the two shows are revealing: Dreaming, a term now reviled by many Indigenous communities for its semantic strictures, relegating Aboriginal culture and beliefs to some distantpast immutable plane of existence, and Ancestral Modern, which posits a glorious and tantalising tension and promise of continuity.

In the didactic text panel to Ancestral Modern’s portrait room, Pamela McClusky, SAM’s Curator of African, Oceanic and Aboriginal art, framed the genre thus: ‘Portraits in Aboriginal Australia don’t follow the convention of depicting a face or even a physical likeness. Instead, these portraits reveal a person’s identity in relation to others, to the land and to the creator ancestors.’ The room offered a bold juxtaposition of works by Tasmanian photographer Ricky Maynard, and Jarinyanu David Downs, Ginger Riley Munduwalawala and Rerrkirrwanga Mununggurr, each from remote communities. Ancestral Modern was co-curated by the NGA’s former senior curator of Aboriginal art, Wally Caruana. Leading a tour through the exhibition space, Caruana was at pains to distinguish European portraiture as identity – based on physical features – from an Aboriginal idea of cultural connectedness, explaining that portraiture can encompass clan designs, enacting an ancestral role though dance, or identifying with an animal totem represented on canvas.

In the Western canon, representations of artists and certain prominent persons can, of course, be conceptualised and recognised by an array of objects that stand in for them, or that reflect their position in society. Think of Van Gogh’s three works depicting his Bedroom in Arles, from the 1880s, or the many depictions of artists’ studios. Portraits can also be hidden within painted representations, such as in the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ painting Nude in a Rocking Chair, 1956 by Picasso, where the artist’s facial features literally carve out the shape of the nude’s torso. Rarely, however, are such works categorised as portraiture.

Ancestral Modern made the point that Aboriginal portraiture encompasses the ‘merging of one’s identity with a heroic icon or designs that cover one’s body at significant moments in ceremony.’ In the painting Kurtal, 1992, Jarinyanu David Downs depicts the ancestral rain maker, the role for which he carried contemporary community responsibilities. Non-figurative works in Aboriginal art should not be discounted as abstract, in the sense of being non-representational. This point was made clear with Rerrkirrwanga Mununggurr’s painting depicting an intricate clan design. Gumatj Clan Fire, 2010 was clearly labelled as a portrait of the artist’s husband, Yalpi Yunupingu, commemorating his role as a custodian of the ancestral fire.

The nexus between identity, cultural responsibility and clan designs featured elsewhere in the exhibition, such as Djambawa Marawili’s Metamorphosis/Djirikitj, 2006, the label for which declared ‘Baru, the Crocodile ancestor, has fire patterns embedded in his skin ... Baru’s image is a cultural self portrait of the artist. Marawili is a tireless and successful advocate for the rights of indigenous people, a ceremonial and community leader and a negotiator in land and sea rights claims. His ritual authority brings with it the responsibility to protect and pass along his clan traditions, to spread the metaphorical fire of knowledge, just as Baru propels flames across his land.’ In the clan design painting Pwoja, Body Paint Design, 2001, Tiwi artist Pedro Woanaeamirri used a wooden comb, or pwoja, to lay down rows of dots over a black background. The label noted that pwoja create distinctive designs that become the mark of individuality, and that Woanaeamirri likens the pwoja to a bone in his body, a fundamental part of his identity.

While connection to country and culture is routinely propounded in works by artists from remote communities, the art of practitioners working in the long settled states of Australia has a heavy focus on reclamation and critique. Many urban-based Indigenous artists, as well as those having grown up in semi-rural and regional missions, have suffered dramatic disruption and dislocation to family, culture and traditions. Reconnecting with lost or fractured culture and family is a common theme, as is addressing colonial subjugation. And within this paradigm, portraiture takes pride of place, staring down those that resist the re-reading and re-telling of Indigenous history.

Western Australian Badimaya woman Julie Dowling is unique among Indigenous artists in her sole focus on portraiture. Dowling’s recent lived family experience forms part of the Stolen Generation narrative. The artist has recounted that she paints her family’s faces (in her estimate, more than one hundred) so she might recognise lost family members on public transport, but she also paints portraits in order to touch a nerve. In Anna Edmundson’s appraisal, it’s the ‘strong sense of anima’ in her portraits of Indigenous people that triggers empathy in the viewer. Dowling’s family’s cultural dislocation dates back to colonial times. In a review of the exhibition Strange Fruit: Testimony and Memory in Julie Dowling’s Portraits at the Ian Potter Museum of Art, 2007, Maura Edmond writes that Melbin, 1999 – a portrait of the artist’s great-great grandmother – exposes ‘the tremendous irony inherent in the British Empire’s colonial concepts of savagery, nobility and royal patronage’. Melbin was paraded in 19th-century English society as a ‘Savage Queen’. In the portrait, her halo is embellished with iconography of the colonial slave trade – ships and manacles – and her compromised identity is summed up by the luggage tag on her wrist, which simply reads ‘Melbin. Portsmouth’.

South Australian artist Yhonnie Scarce, and photographer, video and performance artist Christian Bumbarra Thompson, of central Queensland Bidjara heritage, each tackle issues of colonial subjugation and the fracturing of identity in vastly different ways, utilising portraiture as a trigger. Scarce describes her work as ‘politically motivated and emotionally driven’. In Oppression, Repression (Family Portrait), 2004, handblown glass bush foods sit atop images of family membersbottled in preservative jars – a powerful statement about the lasting impact of colonial policies designed to fracture Indigenous culture and how Indigenous people are still contained and constrained by the perspectives, policies and practices of white hegemony.

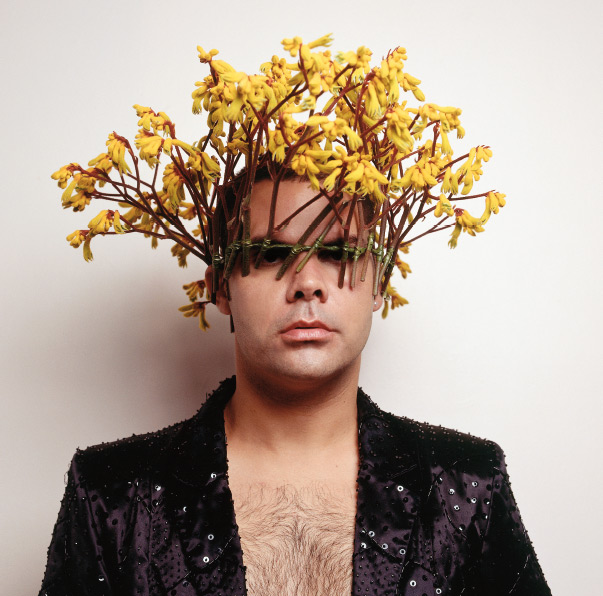

Thompson’s self portraits with headdresses of native flowers from the Australian Graffiti series are often considered critiques of the ethnographic practices of categorising and classifying Aboriginal people, who were, after all, shamefully considered part of the nation’s fauna and flora until relatively recently. More directly, they reflect the artist’s approach to Indigenous culture as something ‘hybrid, living and contemporary’, and serve as a commentary on his personal identity: ‘I think of the flowers as a particularly Australian palette … they feel like allies in many ways, we come from the same place.’ Queensland-based ProppaNow artist Vernon Ah Kee is unequivocal in his politics, both in relation to race and to Aboriginal art, which he sees as a white construct. In an expansive and innovative contemporary practice that periodically foregrounds his drawing skills, Ah Kee has utilised large format portraits of male family members to challenge prevailing stereotypes.

In neither pride nor courage, 2006, the artist subverts the photographic portrait triptych, a preserve of anthropologists. His grandfather’s sedate three-quarter portraits feature a glass slide, traditionally used to record ethnographic details. Ah Kee usurps the final ‘right profile’ shot, replacing it with a bold image of his infant son’s head with glaring stare – and in so doing he thumbs his nose at colonial history and its ‘dying race’ theory. The glass slide remains, documenting Ah Kee’s mixed heritage and proud claim of ‘Blackfella Me’.