Watkin Tench, a military officer who sailed to New South Wales with the First Fleet in 1788, penned what some consider one of the most valuable and readable accounts of Sydney’s first few years.

In early 1790, this was the situation in the settlement as he recalled it: ‘We had now been two years in the country, and thirty-two months from England, in which long period no supplies except what had been procured at the Cape of Good Hope by the Sirius had reached us. From intelligence of our friends and connections we had been entirely cut off, no communication whatever having passed with our native country since the 13th of May, 1787 … Famine besides was approaching with gigantic strides, and gloom and dejection overspread every countenance’.

Tench’s account goes on to describe various other marks of dejection exhibited by the colonists when no amount of stoicism could completely dispel the suspicion that they’d been abandoned. For eighteen months, patrols had been dispatched every week for Botany Bay to see whether a ship had shown up there mistakenly; and ‘every morning from daylight until the sun sunk’, the poor sod stationed at the flagstaff on South Head would ‘sweep the horizon in hope of seeing a sail’. Their despair plumbed even greater lows when captain John Hunter’s ship Sirius, one of only two lifelines to the outside world and having already escaped a close call off the coast of Tasmania, was wrecked on a reef at Norfolk Island in March 1790.

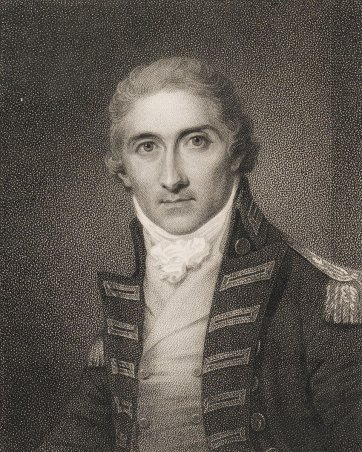

Given that state of mind, it was probably better that the colony was oblivious to the grim fate of a ship called the Guardian that had left England in early September the previous year. Under the command of Lieutenant Edward Riou (1762–1801), still in his twenties but already a veteran of service in North America, the West Indies and of Captain Cook’s third Pacific voyage, the Guardian was laden with food, seeds, livestock and agricultural equipment intended for Sydney, as well as a contingent of convicts and their superintendents. The ship had an uneventful trip as far as Cape Town, where Riou took on even more provisions before departing on the leg to Sydney on 12 December ‘with the pleasing idea of the Consequence we should be of to Governor Phillip and his Infant Colony’.

About ten days later, however, the Guardian ‘fell in with several Islands of Ice, floating in the Ocean 400 leagues from land’. According to Riou’s account of what followed, he judged conditions to be favourable enough for him to sail closer to the icebergs so as to collect floating slabs of ice to supplement the ship’s supply of fresh water. The weather then deteriorated. The same evening, 24 December, the fog so dense that the mariners were unaware of the danger, the ship struck what Riou recalled as ‘a body of Ice full twice as high as the Masthead and just showing itself through the thickest vapour I ever breathed in’. ‘The ship’, he continued, ‘was now entering into a vast Cavern which appeared to be high & large enough to devour her entirely’.

Around about the time that Tench and other chaps were attempting to generate Christmas spirits with their diminishing rations in Sydney, Edward Riou was contending with a vast gash in the Guardian’s side, its hull rapidly filling with seawater, the keel ruined and the rudder ripped off. Having managed to sail the ship clear of the iceberg, the crew worked desperately at pumping water out of the hold. On Christmas morning they attempted to patch the hole in the ship’s side by strapping a sail over it; and when this failed to diminish the peril, Riou ordered that all heavy objects – livestock, guns, anchors, cargo – be thrown overboard to lighten its load. By this time, with all efforts at saving the ship seemingly failing, some members of the crew had decided to escape in the Guardian’s longboats. Riou, acknowledging himself that ‘little chance was left of safety’, agreed to their pleading and roughly half of the Guardian’s company then abandoned ship. In typical noble captain fashion, Riou ignored the ‘intreaties’ of the deserters and chose to stay on board with sixty others, twenty-one of whom were convicts. ‘The agitation of the mind on this melancholy occasion, may be better imagined than described’, stated the account of one who opted to flee: ‘never did the human mind struggle under greater difficulties than we experienced in being obliged to leave so many behind, in all probability to perish.’

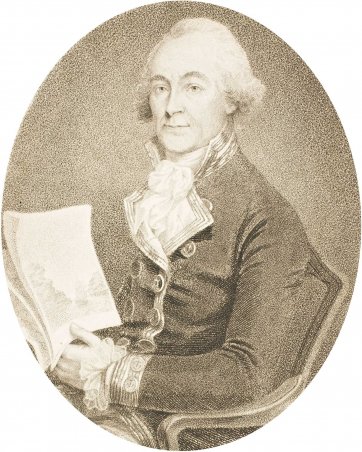

This dramatic, despairing perspective was later adopted in depictions of the disaster, such as that printed by Robert Dodd in London in 1790. Dodd (1748–1815) – trained as a landscape painter but better known for his images of ships, dockyards, naval battles and marine scenes – was one of many English publishers and printmakers whose trades appear to have been underpinned by the nation’s fixation on oceans, exploration and voyaging and by its appetite for rollicking, rousing tales of maritime terror and glory. Dodd’s output, between the 1780s, when he began exhibiting at the Royal Academy, and his death in 1815, included paintings and prints of the battles of the Nile and Trafalgar, portraits of famous ships (he was apparently highly regarded for his accuracy in painting details such as sails and rigging), and representations of dramatic incidents – including the moment at which William Bligh was cast adrift in the Pacific by the mutinous crew of HMS Bounty in April 1789. As with his depiction of Bligh and the mutineers, Dodd’s image of the Guardian is spiced with doom and portent, emphasised by excerpts, printed in the margin, from a letter Riou wrote as the ship foundered and in which he anticipated there being ‘no Possibility of my remaining many hours in this world’. Dodd’s print was equally, however, designed to stoke feelings of pride and fervour in Britain’s capacity to breed mariners of Riou’s ilk: ‘a man of sound and comprehensive understanding’, according to one account of him, ‘both elegant and manly … with a countenance expressive of heroism, sense and benevolence’. For, like Bligh, with whom he had sailed during Cook’s third voyage, Riou’s disastrous 1789 southern experience concluded with a somewhat unbelievable degree of luck and courage and a remarkable feat of seamanship. Just as Bligh, having been left for dead with eighteen others, sailed an open boat nearly 6,000 kilometres to safety, Riou managed to keep the Guardian’s remaining crew in line and the stricken, sinking vessel afloat for two months until it drifted within sight of Cape Town in February 1790.

Unsalvageable, the Guardian was broken up and scuttled in Table Bay soon after being rescued. Riou returned to England a hero and was honourably acquitted of any blame for the loss of his ship in the obligatory court martial that followed, soon making his likeness and accounts of the Guardian’s horrendous voyage perfect fodder for Dodd and other purveyors of stirring, supposedly ennobling images. Riou was later promoted to the rank of captain and served on a series of gunships during the French Revolutionary Wars, losing his life in the Battle of Copenhagen – another of Dodd’s subjects – in April 1801. Whereas all but fifteen of the people who’d fled the Guardian perished, everyone who remained on board with Riou survived. The salvaged cargo, passengers and convicts originally slated for Sydney were distributed among the ships making up the disastrous Second Fleet when they called at Cape Town. They eventually arrived in New South Wales in June 1790, bringing with them the first contact that Tench and his colleagues had had from home in more than two years, as well as the bittersweet news of the boatload of food that went down just when the settlement was in the most dire and desperate need of it.

Considered by some Australia’s answer to the sinking of the Titanic, the wreck of the Guardian in 1789 is an event which – in its subtext of the unfathomable pressures felt by those engaged in the early years of the Australian colonial endeavour and in the way their experience was inescapably defined by oceans and distance – underlines what a monumentally chancy and experimental undertaking it was to transplant a version of England to Sydney. Robert Dodd’s representation of the disaster might therefore be seen as an image which enlivens and animates the narratives, by Tench and others, relating the truth of Sydney’s time as a hungry, dishevelled and despairing place at the end of earth.