Diogenes of Sinope declared himself to be a cosmopolitan and when asked from what country he came the Greek philosopher famously replied, ‘I am a citizen of the world’. In Ingvar Kenne’s exhibition of portraits titled Citizen we grasp a similar sense of the connectivity of human lives regardless of place or distance.

Photographed in Australia, China, Laos and Papua New Guinea, Kenne's portraits contain a diverse representation of subjects: from public figures to the anonymous to Kenne’s own family. Kenne is emphatic that there is no narrative connecting the people and that the photographs were captured with no preconceived story in mind. Instead, they are united under the broad theme of people that Kenne met over the course of a decade. Every photograph in Citizen provides a snapshot into the narrative of the subject’s life.

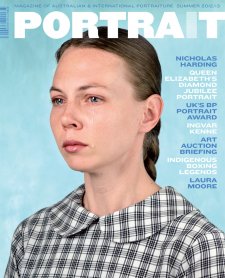

At times, these glimpses carry overwhelming undercurrents of seriousness and sadness, as in the portrait of Kenne’s wife, Anna, with her tear-stained shirt and tear-streaked face. In others we perceive nuances of hope amidst immense pathos, as in the portrait of writer Alexis Wright who stands in the charred remains of Kingslake, Victoria after the 2009 bushfires. To her right is a sprout of green foliage conveying the promise of rebirth amidst destruction. Other portraits carry elements of playfulness like that of the artist Angus Young who plays up to the camera in a self-embracing pose. What all of these portraits hold in common despite these changing moods, is their ability to present us with a fragment of the stories which make up people’s lives. Throughout the photographs of Citizen we sense Kenne’s unique ability to present seemingly spontaneous or simplistic portraits which have, in fact, been informed by his immense faculty and understanding of the medium. When Kenne won the National Photographic Portrait Prize in 2009 with a portrait of his two sons, Cormac and Callum, this quality shone through. The visual arts writer for The Daily Telegraph, Elizabeth Fortescue, disagreed with the choice. For her the photograph ‘just doesn't cut it – either as a family snapshot or as art’. Fortescue’s criticism, somewhat ironically, discloses the success of Kenne’s portraiture. It is this deceptively simplistic quality that enables his photographs to work as impromptu but intimate portraits and encourages us to feel a sense of familiarity with his subjects.

Kenne’s informal style might be related to his openness toward who becomes the subject of his portraits. In his 2004 publication, Chasing Summer, he documented the interesting people and places encountered during a two year around-the-world motorcycle trip. Kenne states that the photographs of Citizen were taken in ‘places I happened to be in during this time and of subjects who met me and my camera’. In fact, Kenne is quite candid that he doesn’t ‘chase the subject’ of his portraits. When asked if this open-minded approach required him to give up a degree of control, he replied ‘I do let go of controlling who will be photographed, but at the same time I am exactly aware of what will appear within the square and where that person is in relation to that space’. Throughout Citizen we grasp this sense that the portrait is a reciprocal or mutual engagement – while the vision of the photographer is paramount the subject can bring their own input. Kenne is aware of this and claims that ‘the final image that catches my attention is always if the sitter breaks through my control and surprises me’ which can be with ‘a faint gesture’ or by ‘emoting that little something I can’t direct them towards’. At the same time Kenne explains that the control which his subjects hold is not so much an ‘influence over the photograph’ but rather, a control over their response to him, ‘because the final decision and choice of frame lies with me, I wrest some of that control back’. A number of the portraits in Citizen arose from commissioned work in which both parties are aware of why they are working together. Kenne finds that this can make the process both easier and harder as his subjects approach the portrait ‘accepting the fact, but they might also come with a sense of caution because of it.’

Despite the celebrities scattered throughout Citizen there is equality among all of Kenne’s subjects. He gives all of his sitters – actors, artists, newsreaders, and the anonymous – the same treatment. This was certainly the case when Kenne had to make his final selection for the series and he stressed that, ‘there are many images which obviously never made the final cut and the reason for that decision is always my relation to the photograph, and not to who they are. Many a celeb didn’t make the cut’. Kenne reflects that ‘it’s been a fairly democratic process’, and that even in portraits of celebrities the ‘public persona is almost beside the point.’ A portrait of SBS newsreader Lee Lin Chin illustrates this perfectly, with little to suggest her identity within that profession. Chin stands barefoot in an alleyway, turning her hands outwards to accentuate the cut of her sleeves. From this set-up we recognise Chin’s interest in fashion and design, but the setting is in stark contrast to the formality of the newsdesk. Kenne captures something of Chin’s personal self rather than her public self. Similarly, in a portrait of two anonymous sitters photographed in Mount Hagan, Papua New Guinea, we sense that the finer details like occupation or name are irrelevant, or at least, not imperative toward grasping a sense of their individual lives.

Despite Kenne’s assertion that these photographs were taken with no overarching narrative in mind, they all seem united in their ability to give insight into what being a citizen can entail. The title for this series arose from Kenne’s need to articulate this link between the portraits. ‘I realised that my intent walking into a portrait session had been the same for the last twenty years and hence a collective had been formed with strong bonds between' them. So I needed a title that emphasised that connection.’ This connection of citizenship instilled in these portraits is not related to specific countries or nations but in the words of Diogenes, a citizenship to the world. The respective homeland of each subject seems inconsequential. Instead, what stands out is the realism of human experiences contained within these snapshots of individual lives. When asked what it meant to be a citizen Ingvar replied, ‘Having travelled to quite a few countries in the last twenty years the word citizen has come to signify the similarities between people and what unites us, not what differentiates us.’