I first came face to face with portrait painting when my best friend at school decided he would go to art school. At the age of about fifteen he put himself through a tough self-taught apprenticeship of drawing and painting, going to exhibitions, reading the biographies and diaries of painters and listening to jazz.

Almost all our time together was taken up with him either doing this stuff or talking about it, and a good deal of it was taken up with drawing and painting self portraits. He kept experimenting with paints and surfaces: many different kinds of paper and card, wood and cloth. He used oils, but he also started mixing glue into household paint or school powder paint.

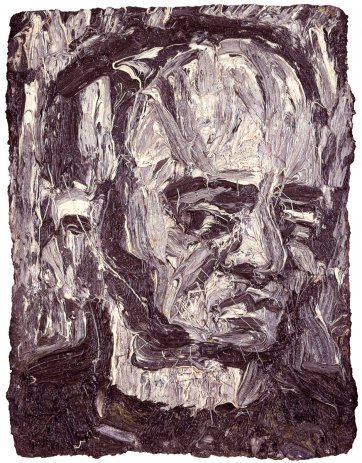

I can now see some fifty years later that this energy and diversity, focused in on what was often a lonely exploration of himself, put me in awe. I wanted to have inside me that inner thing that was driving him, so that it could drive me somewhere. Of the drawings and paintings themselves, I was never quite sure. He kept saying they were rubbish, but it just made him want to do more. I went on looking and wondering until one time I went over to his house in suburban north London and he showed me an oil painting he had done. Again, it was of himself, but he hadn’t done it from life, he said. He had been coming home on the Tube at night, in the window. He said he had remembered it, dashed in, got out a bit of hardboard and put the oil on in great thick splurges. When I looked at it, I was stunned. In my eyes, he had captured in these swirls the shadow of introspection that often crossed his face, the slightly spoiled puffiness of his cheeks, the self-conscious artiness in the way he carried his head and neck – it was all there. And yet it wasn’t a likeness. How had he done that? It seemed like magic. He had captured a state of mind, a sense of moment in a life in these thick blobs of oil. In the thickness of it, he had even caught the odd angle of his eyebrows when he talked earnestly about Van Gogh or Charlie Parker.

I remember saying to him that I thought it was brilliant and so he gave it to me. I’ve kept it with me all my life. I’ve propped it up on top of books, on windowsills, up against pillars. We stopped seeing each other some forty years ago, I think. We both know where we are. He is much taken up with philosophy and Sanskrit culture. He didn’t stick with painting, even though there was a strong presence of it in his family with his cousin being a celebrated international artist. But I have this painting, which I think expresses a person, a time, a state of being, a thought, a longing. Very nearly every time I’m on the Tube and I see my reflection in the window opposite, I think of the painting and I think of him and I think of the creative passion of those times. In fact, I stole some of that in my own work – and still do. But something else: it took me to looking at the painting of faces, portraits and self portraits.

In what was at the time slightly irritating, he would often do that thing of leading you to someone well known but then either discovering a work that no one else had ever mentioned or saying: if you think he’s great, have you ever heard of so-and-so? This is what he did with Augustus John. John was on his last legs but enjoying a reputation that teenage boys like us wanted to be part of. I seem to remember that there was a BBC arts programme about him that was appropriately scandalous. My friend could cap it: never mind him, it’s his sister’s stuff you want to look at. At the time, I didn’t know why he said that. All I know now is that whenever I come across a Gwen John painting I have a strong sense that this is someone I once knew, a woman who was sadder than she wanted to be. In English, we put many seemingly inconsequential words in front of nouns – ‘the’, ‘a’, ‘some’, ‘any’ – but they all mean a lot, and even the lack of any word has a meaning.

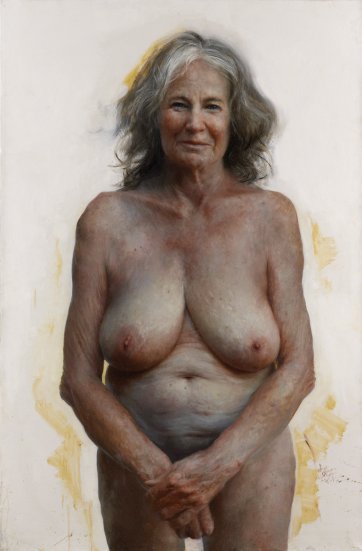

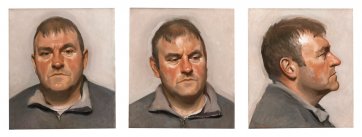

As a game, I sometimes try standing in front of a portrait and ask: is the unsaid title of this painting ‘The Woman’ or ‘A Woman’, ‘My Woman’, ‘Her Own Woman’, ‘Woman’, ‘Some Woman’, ‘Any Woman’, ‘That Woman’ … or what? Of course, it could be several at the same time. Isn’t there a way of looking at Lucian Freud’s pictures of himself in which we might say that the title is ‘My Own Man’ and ‘Man’? One way to reach those general truths and thoughts about our humanity is through the most detailed, specific exploration of one individual, it seems. My friend stood me in front of Freud’s paintings at an exhibition in the early 1960s, then in front of a painting by his cousin, Leon Kossoff, whose work was included in the same show, and said that he wanted to paint like that.

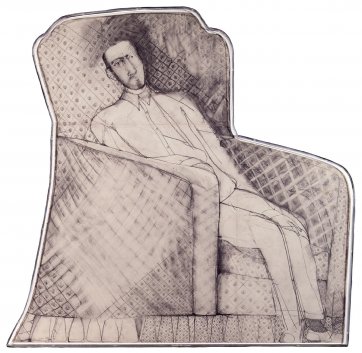

In the end, it wasn’t the route he wanted to take, but a few years later another friend, similar in some ways to the first – full of esoteric enthusiasms – said that he knew a great artist who not enough other people thought was great: Anthony Green. I agreed. Looking at them now, I think that what Green does with the pictures of himself embedded in his past and present seem oddly close to how I have put my friend’s Tube train self portrait into my memory and daily life: portraits in lived-in rooms – or is it, rooms with lived-in portraits?