Lionel Rose’s win in the world bantamweight title fight in Tokyo in February 1968 ignited elation in his homeland. As one Sports Illustrated journalist later described it: ‘The fight was not televised, but all across Australia that night people clung to their radios as if the ringside announcer were Winston Churchill.'

'And when Lionel Rose was awarded the championship, the continent went wild … Women wept over Lionel Rose and men shouted. Autos pulled off the road so strangers could embrace in the headlight beams and the Prime Minister sent Rose a wire of congratulations.’

In wresting the world bantamweight title away from his opponent, the Japanese boxer Masahiko ‘Fighting’ Harada, the nineteen-year-old Rose had become the first Indigenous Australian to win a world sporting title and the second youngest man ever to claim a boxing world championship. Rose was later named 1968’s ABC Sportsman of the Year and Australian of the Year – the first Aboriginal person to be thus honoured.

No surprise, then, that Lionel Rose occupies a rightful and illustrious place in the canon of Australian sporting achievement. But nor is it odd to find his name lodged in the lexicons of those with no more than a vague, passing or reluctant knowledge of boxing. Just as his predecessors like Les Darcy and Jimmy Carruthers earned popular hero status for having, through boxing, turned blue-collar backgrounds and rudimentary educations into wealth and repute, Rose’s success was of the variety that appealed to sports-loving compatriots and their deep admiration for underdogs and true grit. Born in a makeshift settlement in Gippsland, Victoria, in 1948, Rose had taken up boxing in emulation of his father, Roy Rose, an erstwhile tent-show fighter, and entered the game full time when Roy’s death in 1963 left his family without a breadwinner. Five years later, he had proved boxing’s worth as a method of creating prosperity and acceptance in the presence of disadvantage and discrimination. Yet Rose, though well remembered in part for being the first Indigenous boxer to acquire world champion status, was hardly the first contender for that distinction. Many believe it’s one that might easily have gone, sixteen or more years earlier, to a Newcastle-based middleweight named Dave Sands had he lived long enough for the opportunity to earn it. If there was one thing that took the shine off Lionel Rose’s 1968 triumph, in the words of the same Sports Illustrated writer, ‘it was a sense of sadness that other fine Aboriginal fighters before him had never been given the same chance’. Whereas the significance of and response to Rose’s achievement was augmented by its taking place in a landmark decade for Aboriginal rights in Australia, the experiences of Dave Sands, his five boxing brothers, and many other Indigenous fighters have since been cited as proof that their careers, no matter how great their successes, were blighted by exploitation, mismanagement or prejudice.

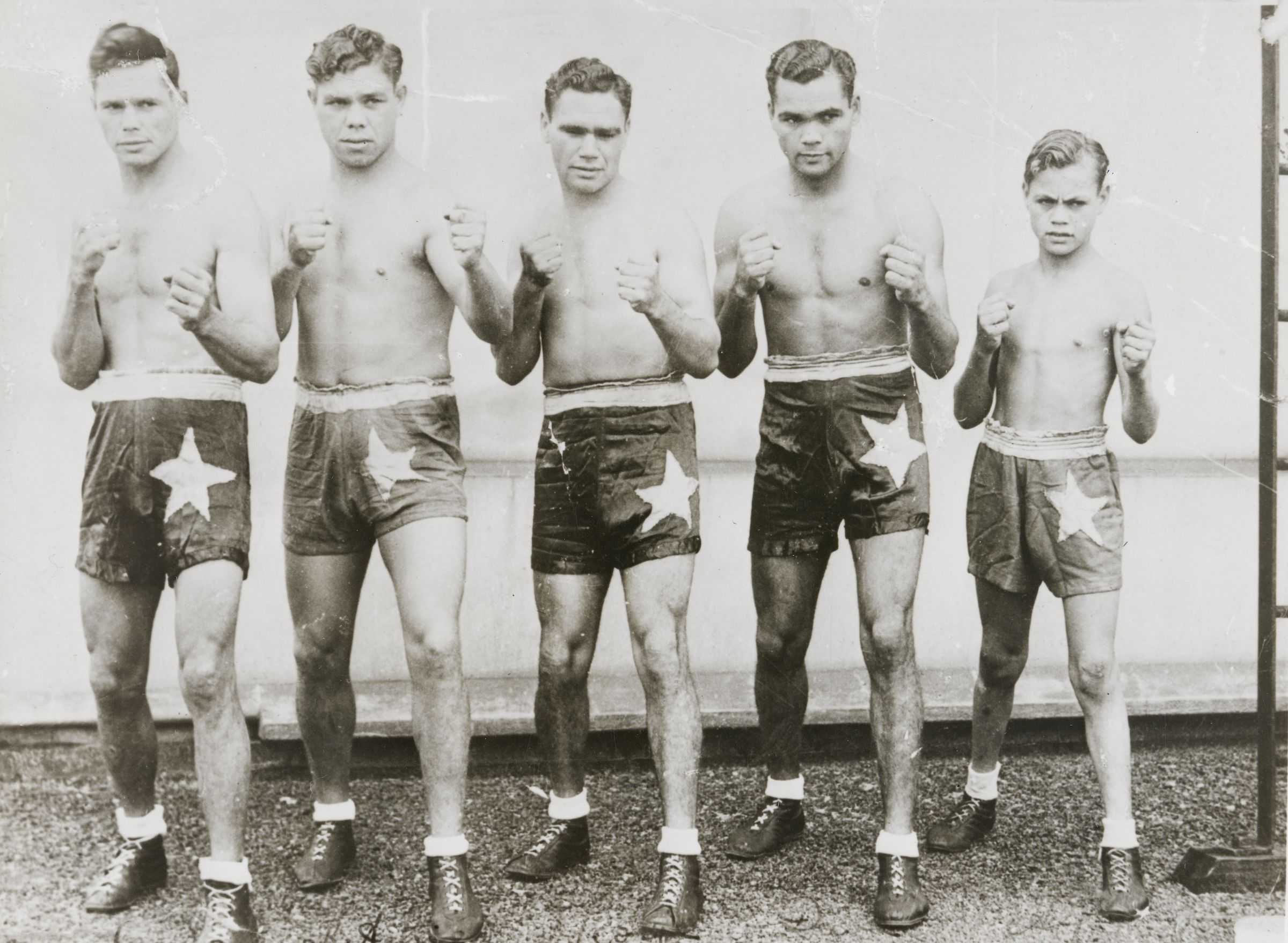

At his peak and at a time when stadium fighters rivalled cricketers, footballers and racehorses for a top spot in public affections, Dave Sands (1926–1952) garnered genuine regard in Australia and overseas, often as much for his affability and modesty as for his exceptional talent. He was one of a sextet of boys from the same family that – between 1939, when the first of them entered the ring, and 1959, when the youngest retired from it – fought over 600 bouts between them, winning a third by knockout and tallying up nine titles at state, national and Empire level. Like Rose, the brothers – who were born with the surname Ritchie but boxed under the more marketable ring-name ‘Sands’ – were introduced to boxing at young ages and by way of family, their father, George Ritchie, and an uncle named Bailey Russell, having taken part in boxing tent and bare-knuckle bouts with some success. Following their father’s death in the 1930s, the second eldest of the brothers, Percy (1921–1974) – who fought as Ritchie Sands – left home in Kempsey with the aim of earning some extra money for his family. Percy was taken on by a trainer named Tom Maguire in Newcastle in 1939, doing odd jobs and errands for Maguire in exchange for lessons and shelter. Dave joined Percy at Maguire’s gymnasium, called the ‘Northern Star’, aged fifteen, in 1941, and by 1948 had been followed there by another three brothers, George (1924–1986), Clem (1917–1989) and Alfie (1929–1985). Clem and Alfie and the youngest brother, Russell (1937–1977), who joined Maguire following Dave’s death in 1952, each won state or national championships: Clem was New South Wales welterweight champion from 1947 to 1951; Alfie the state’s middleweight champ between 1952 and 1954; and Russell both the state and national featherweight titleholder for 1954.

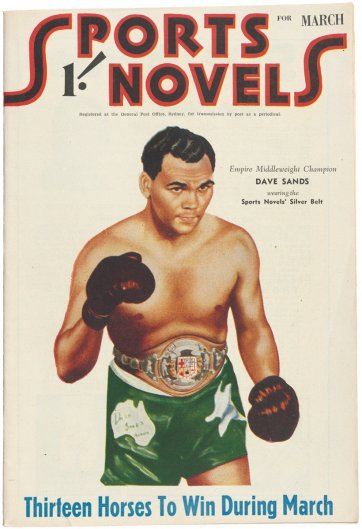

Dave, the most famous and successful of them, won his first Australian middleweight championship in 1946 and later, for a three-year period, held the middleweight, lightheavyweight and heavyweight titles simultaneously. When Dave Sands was declared the Empire middleweight champion in London in 1949, having knocked out his fancied and quaintlynamed British opponent, Dick Turpin, in the first round, Australian papers gloated about ‘the boom boxer of the year’ with his ‘killer punch’, ‘rare courage’ and firm prospects for a world title. His death at the age of twenty-six three years later saw Australian boxing, in one reporter’s opinion, ‘brought to one of the lowest ebbs in its history’. Boxing writers lamented that Sands’ passing – with, allegedly, a chance at a world championship bout in the offing – had left Australia ‘without a worldclass fighter’ in any weight division, while hundreds of fans and businesses contributed to efforts to raise money for his wife and family, left broke despite the many thousands of pounds he’d earned in the ring.

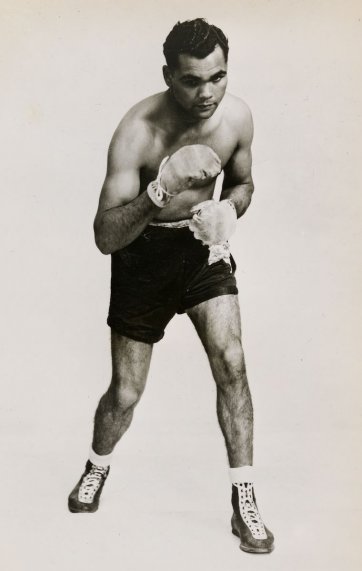

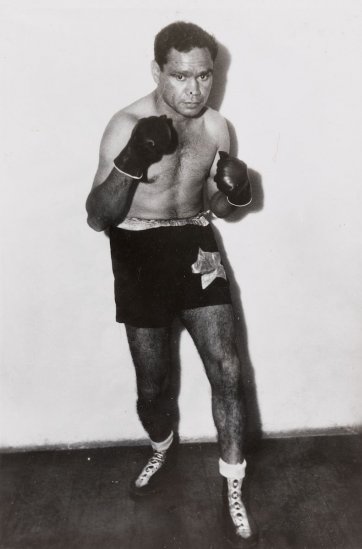

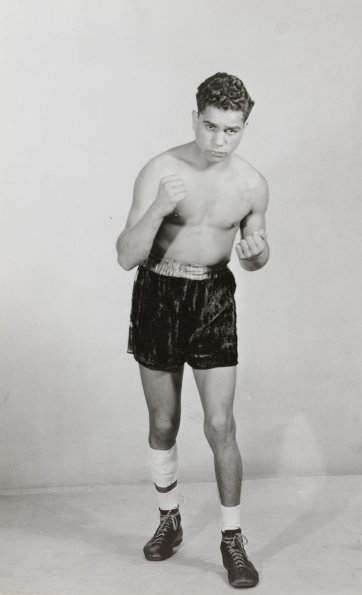

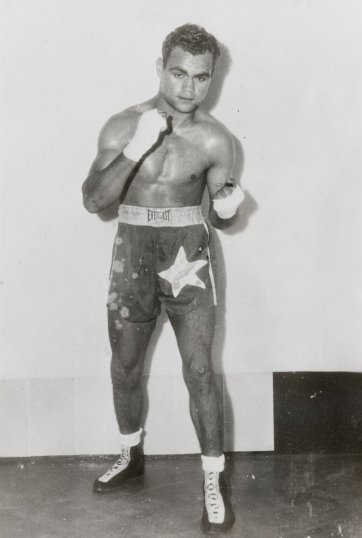

The degree of admiration for Dave Sands is easily discernible from the images and anecdotes of him and of his ‘Fighting Sands Brothers’ in their star-bearing, green satin shorts that were in circulation throughout his career. Sports fans relished the against-the-odds tale of six brothers raised in a small Aboriginal community on the mid-north coast of New South Wales, timbergetters and woodcutters by trade, who exchanged hardship and obscurity for stardom, albeit of a fleeting and brutal variety. Newspapers related each of their fights (literally blow-by-blow in some cases) and traded in blokey, bar stool tales of the Sands boys: such as Alfie, like Dave, having spent a portion of his wedding night fighting at Newcastle Stadium, with his bride ringside; that Dave, who won two-thirds of his bouts by knockout often did so without raising a sweat; or that they had all supposedly made a pact whereby any fighter who defeated a Sands would be dealt a hiding on next encountering one of the brothers in the ring. And publishers, like trainers and fight promoters, made commodities of them in the form of postcards and fanzine-style photos.

Pugilists had featured in such images since the second half of the nineteenth century, when photography in its cheaper, mass-producible and mass-consumable formats had first been harnessed as a means of cashing in on a population’s admiration for or fascination with public figures. In Australia, the emergence of photography and, in particular, from the early 1860s the availability of the type of photographs that enabled the middling and working-class sections of society to acquire portraits of and for themselves, paralleled the growth in the demand for entertainments and amusements of various descriptions, including sport. Sporting types, whose crafts were a combination of showmanship, athleticism and commercialism, were popular subjects for tradeable portraits – such as cabinet cards, cartes de visite, or cigarette cards – as were actors, dancers, divas, sideshow freaks and other performers. Boxing, imported to Australia by its colonisers, is argued to have had greater currency here for the manner in which it allied itself with ideas about nationalism, masculinity and identity, possibly making its proponents even more appealing as portrait subjects. Some hold that out of the country’s rough and anti-authoritarian convict origins evolved a breed of people naturally disposed to subversive pursuits like betting, boozing and brawling and that, during the 1850s and by occupying the margins of upright Victorian society, boxing appealed as a rugged, real-man pursuit by which one fashioned a sense of Australian masculinity as meaning strong, resourceful, independent and resilient. Later, in the lead up to Federation, sports like boxing became a particularly potent way by which Australians could distinguish themselves as a new and independent breed: young, vigorous and outdoorsy as opposed to effete, pasty and intellectual.

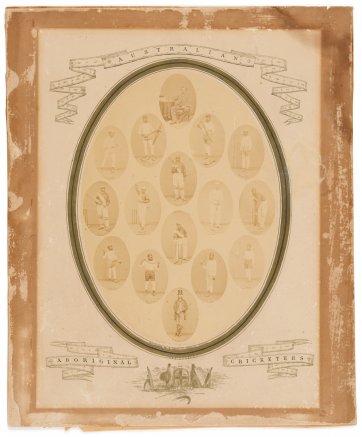

Photographs of Australian boxers taken in the decades either side of 1900 typically conform to an established language and a stiff, clichéd template: the manly pugilist, tough but dignified, depicted with his fists poised, pecs primed and on-guard stance adopted. That the same language was applied to the depiction of Aboriginal fighters might be read as evidence of their equal treatment and of the fact that the boxing arena was one of very few avenues to social acceptance and financial reward available to Aboriginal men. Already a sport that enticed and was open to men of disadvantaged circumstances by virtue of its rawness and simplicity – requiring men to possess merely fists and pluck rather than money – boxing’s appeal was amplified for Aboriginal people who were excluded from most pastimes and professions by discrimination on economic and numerous other terms. Boxing had a democratic, escape-fromadversity flavour that was touted and reinforced by the boxing tent troupes, such as the famed version established by Jimmy Sharman in 1911, in which many Aboriginal fighters got their starts. Boxing tents toured to regional towns and agricultural shows close to reserves where Aboriginal people lived, giving men the chance to earn good money (a week’s wages in five minutes, by one account) and to do so without access to flash equipment and expert training. Accordingly, Aboriginal boxers figure prominently in the sport’s heyday period and on an equal footing with white men like Les Darcy, whose boyishness, agreeable looks and working class roots had helped smooth his way to national hero status. The first in a substantial line of Indigenous boxing stars, Jerry Jerome, won the Australian middleweight title in 1912. Jerome was followed up by fighters such as Ron Richards, the Australian middleweight titleholder in 1933 and again between 1936 and 1942; and Elley Bennett, a national champion in two weight divisions who was denied a crack at the world bantamweight belt for being black and thus not permitted to challenge its white South African holder. As stated by Douglas Nicholls – who, before becoming the first Aboriginal Australian to earn a knighthood, had had success as a sprinter, played football for Fitzroy, and served the odd stint in Sharman’s troupe – for Indigenous people, ‘the only way to crack the white world was to do something better than the white man.’ The alternative argument is that the evidence of the successes, presence and stature of Indigenous men in an industry that was unforgiving and exploitative by nature testifies also to the inequalities that defined their participation in the sport, and in the same way that inequalities between black and white had previously been played out in photographic portraiture. As in Patrick Dawson’s 1867 composite portrait of the Aboriginal cricket team, for instance. The first Australian sporting team of any description to tour internationally, the ‘Australian Aboriginal Cricket Team’ was comprised of men who’d learnt to play cricket while working as stockmen on properties in western Victoria. Organised into a team by their employers and under the tutelage of a non-Aboriginal captain-coach, they took part in a game at the Melbourne Cricket Ground in December 1866 that alerted the team’s managers to its profit-making potential. Dawson, a surveyor and self-taught photographer, took individual portraits of the players before they left for England in early 1868 on a six-month tour that typically saw them contest two or three matches a week, their cricketing performances interspersed with exhibitions of spear and boomerang-throwing and other ‘native sports’. Informed by a code which positioned Aboriginal sitters as curious, unequal and different, it is a portrait that presents its subjects – depicted holding boomerangs and other objects – as novel or amusing representatives of their race as much as it presents them as sportsmen. Likewise, the manner in which men such as the Sands brothers were depicted can sometimes serve to underline not their professions, personalities or achievements, but to remind us of their status as novelties and fine physical specimens. ‘Australia’s dapper, darkskinned, dreamy eyed boxing enigma’ crooned the Adelaide Advertiser of Dave Sands in September 1949 before going on to colour its account of his Empire title win with words like ‘savagery’ and ‘slaughter’. Though perhaps banal or benign when applied to most pugilists, such descriptions – and their visual equivalents – in the case of men such as Sands can be unsettling in the way that they allude to the negative assumptions that influenced the treatment and reception of Aboriginal fighters. Boxing troupe proprietors and fight promoters, for example, are said to have consciously played up to ‘prevailing racial stereotypes’, turning bouts, in the words of historians Richard Broome and Alick Jackomos, into ‘the encounter between dominant and subordinate, coloniser with colonised, ‘civilised’ with ‘savage’.’ Some historians have noted the presence of inherently prejudiced attitudes, such as the belief in the superior, ‘natural’ abilities of Aboriginal fighters, or that they carried an in-built propensity for wildness and wiliness that better fitted them for codified barbarity. While others, such as writer Peter Corris, have concluded that the predominance of Indigenous men in boxing, rather than a positive, was something that ‘reflects the continuation of their disadvantages, for it is almost an iron clad rule that well-housed, fed and educated people do not become boxers.’

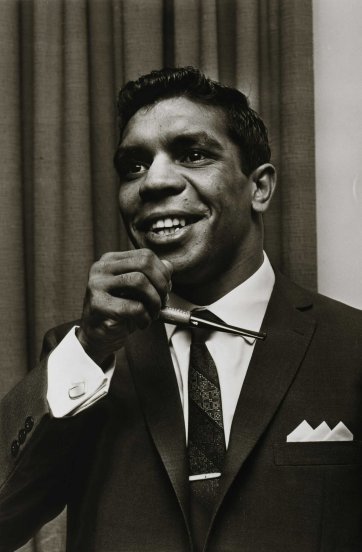

Despite these observations, it’s tempting to see the National Portrait Gallery’s collection of portraits of Indigenous sportspeople, and particularly boxers, as a case study in the shift in representation that has taken place since the 1868 Aboriginal cricketers were posed, perhaps unwillingly, in a photographic studio in Warrnambool. In winning a world championship a century later and in the wake of significant events in the Aboriginal rights movement, Lionel Rose was celebrated in images that, by contrast, signified pride and individuality and put paid to negative and derogatory assumptions about the character of Aboriginal people and the corresponding representation of them in powerless, specimen-style modes. Rose’s 1968 portrait by Merv Bishop – the first Indigenous Australian to work as a professional photographer – and even the modest, mass-produced images of the Sands brothers provide evidence also of the way that boxing created a means for Aboriginal men to achieve recognition and a degree of equality with their non-Aboriginal counterparts, even if that equality, and the appearance of it, evaporated as soon as they stepped outside the ring.