Masquerading as a myriad of characters, Cindy Sherman invents personas and tableaus that examine the construction of identity, the nature of representation, and the artifice of photography. To create her images, she assumes the multiple roles of photographer, model, makeup artist, hairdresser, and stylist.

Whether portraying a career girl, a blond bombshell, a fashion victim, a clown, or a society lady, for over thirty-five years this relentlessly adventurous artist has created an eloquent and provocative body of work that resonates deeply in our visual culture.

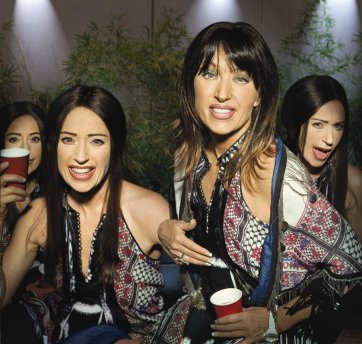

Cindy Sherman’s 2008 society portraits feature women ‘of a certain age’ from the top echelons of polite society: politicians’ wives, old-money blue bloods and the nouveau riche. While the characters are not based on actual women, Sherman makes these stereotypes look entirely familiar. Presented in opulent gilded frames, presumably to be installed in the foyers and grand rooms of their mansions, the characters are both vulgar and tragic. ‘I started to think about some of the characters – how they’re older women and if they are successful, maybe they’re not really happy,’ Sherman said. ‘Maybe they’ve been divorced, or they’re in an unhappy marriage, but because of the money, they’re not going to get out. That’s what I was thinking – that there’s something more below the surface that you can’t really see.’ The Characters are set against the backdrop of opulent palazzos, lush gardens and elegant drawing rooms, holding lap dogs or wearing ball gowns – all familiar signifiers of money and status. To create the portraits, Sherman photographed herself against a green screen and later inserted digital backdrops that she shot herself, in Central Park (Untitled #465), the Cloisters (Untitled #466) and the National Arts Club in Gramercy Park (Untitled #474) among other locations.

The bejeweled and begloved women in these pictures struggle with the impossible standards of beauty that prevail in our youth- and status-obsessed culture, and more that a few of them show the telltale signs of cosmetic alteration. The large scale of the pictures allows viewers to see certain key details very clearly: papery skin around the eyes and lips, the turkey neck that is the bane of older women everywhere, impossibly smooth foreheads thanks to Botox, and arm fat that won’t dissipate despite a daily Pilates regimen. The psychological weight of these pictures comes through the unrelenting honesty of the description of aging and the small details that belie the attempt to project a certain appearance. In Untitled #476 a woman sits on a sofa with her Schnauzer, but the dog is fake. In Untitled #466, a grand dame wears an opulent caftan, but her feet are stuffed into pink plastic slippers from a dollar store and she’s wearing the kind of thick stockings that reduce varicose veins. Upon careful viewing these pictures reveal a darker reality lurking beneath the glossy surface of perfection. In a world where nobody knows who has had work done or what is fake, the series confounds viewers leaving them unsure of what is artificial and what is real. It would be easy to dismiss the pictures as callous parodies, but Sherman’s attention to the details (aging hands, just the right earrings, perfect hair) reveals her intense fascination with and empathy for the women she portrays. A sense of personal connection with her characters seems stronger here than in any other body of work: ‘To me, it’s a little scary when I see myself in these older women.’ Sherman has always included older characters in her work, but as Abigail Solomon-Godeau pointed out in her 1991 essay ‘Suitable for Framing: The critical recasting of Cindy Sherman’, ‘that such types have become critically invisible grimly parallels their invisibility in real life.’ Here, women ‘of a certain age’ loom large, unmistakably visible.

With this series Sherman doesn’t critique just ideas of glamour and standards of beauty; she also takes on issues of class. Although the artist did not conceive of these characters as art patrons, Sherman herself has attained celebrity status within the art world, and these are among the types of women she now mingles with. Sherman takes on a subject that challenges her collectors, and one of the many paradoxes of this series is how the patron class is both the champion and the subject of it. As with much of her work, Sherman has a remarkable capacity to channel the zeitgeist. These well-heeled divas presage the end of an era of opulence with the financial collapse in 2008. The size of the photographs alone seems a commentary on an age of excess and the overcompensation of wealth and status. At this scale the characters’ facades are on full view, making it easier to decipher the vulnerability behind the makeup, jewelry and fabulous settings. The pictures represent a synthesis of the opposing compulsions that plague women: bodily self-loathing and the quest for youth and status. In the infinite possibilities of the mutability of identity and gender, these pictures, like other of Sherman’s best work, stand out for their ability to be at once provocative, disparaging, empathetic and mysterious.