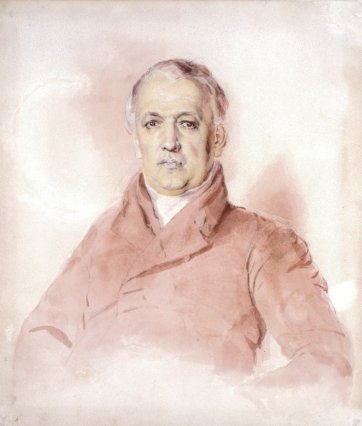

Thomas Griffiths Wainewright is the most intriguing of the varied personalities populating colonial Australian art. A painter, writer, critic, voluptuary and man-about-town, Wainewright had moved in elite intellectual circles in England before being found guilty of forgery and transported to Van Diemen’s Land in late 1837.

In between this time and his death in Hobart a decade later, Wainewright created a small but potent body of work since seized on by art historians for its finesse and by others for the sample it allows one to draw of colonial society’s texture, structure and content.

Considered by some art historians to be the most accomplished of the artists who came here as convicts, Wainewright appeals deeply also as someone who produced portraits by which the workings and intersections of the community he inhabited can be mapped; and as an individual whose ultimately sad and stunted experiences in Australia present a compelling case study in the chancy nature of convictism and exile.

Born in Richmond, Surrey, in 1794, Thomas Griffiths Wainewright was orphaned at an early age and raised initially by his maternal grandfather, Ralph Griffiths, a publisher and founding editor of the Monthly Review who counted thinkers such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Josiah Wedgwood and William Blake among his intellectual associates. Wainewright was around seventeen when he commenced study under the English landscape and portrait painter John Linnell. This lasted just under a year; and an apprenticeship to the society portraitist, Thomas Phillips, was similarly short-lived. He then, in 1814, bought a commission in the army but sold it the following year. By the early 1820s, Wainewright was publishing articles and reviews in Blackwoods and the London Magazine; developing a collection of prints; and exhibiting his work at the Royal Academy, where he befriended artists such as Henry Fuseli. This dandified, elegant lifestyle, however, soon burnt through a £5,000 inheritance and Wainewright took to resolving his financial problems by forging signatures in order to get access to funds he had placed in trust for his wife, Eliza, whom he’d married in 1817. In 1831, he left his wife and son in England and went to France to escape both the likelihood that his financial transgressions would be uncovered and the darker suspicion that he’d played a hand in the deaths, between 1828 and 1830, of his uncle, mother-in-law and sister-in-law, by each of which Wainewright and his wife stood to make money. Though it was never established that Wainewright had, as rumoured, poisoned his relatives, there was more than enough grounds to get him for fraud. Wainewright, accordingly, was snared almost as soon as he returned to England in June 1837 and tried at the Old Bailey on a charge of attempting to defraud the Bank of England. Found guilty, Wainewright was sentenced to transportation to Van Diemen’s Land for life and despatched for Hobart aboard a ship called the Susan, arriving in November 1837.

Wainewright, it has been said, came to the colony with a reputation as a poisoner, seducer and otherwise undesirable individual, but the official records documenting his presence in the convict system offer a more colourless and procedural picture. His conduct record notes that he was well behaved while on the hulks awaiting transportation and makes no mention of his supposedly evil character. He was merely a pale-complexioned painter; brown-haired, grey-eyed, forty-three years old and estranged from his family and guilty of ‘forging a power of attorney in order that the money which was left to my Wife might come to me.’ Not the saucy or sordid story of a vicious, Byronic rake, the narrative of Wainewright’s time in Hobart instead bears greater resemblance to that of a model prisoner who managed, whether out of desperation or resignation, to retrieve something of worth from pitiable and ignominious circumstances. The portraits Wainewright created in the course of the ensuing decade serve as evidence of the degree to which certain convicts adapted to local conditions, illustrating that somewhat perverse aspect of early colonial Australian art that resulted in a significant proportion of it being produced by those who had no choice about being here.

While his convict experience was not necessarily one of complete success or redemption, Wainewright demonstrated an ability to manipulate his position and appears to have begun to enjoy a certain level of latitude while still in a relatively early phase of his sentence. Obviously not by temperament, experience or constitution one who was likely to last long on the road gang to which he was initially assigned, it has been suggested that Wainewright’s good behaviour and poor state of health saw him rewarded with lighter labouring duties within several months of arriving in Hobart. Wainewright’s convict status – specifically his being an inmate at the Prisoners Barracks and, later, an orderly at the Hobart Hospital – brought him into contact with those who, whether out of sympathy or genuine regard, came to be his most useful and attentive friends and supporters. Wainewright’s first Tasmanian portraits, correspondingly, are those of the officials he encountered and those of their families and associates, painted on commission and sometimes out of gratitude on the artist’s part to those who had been kind to him.

Portraits in this category – and some of Wainewright’s most famous and moving Tasmanian works – include those of siblings Jane and Lucy Cutmear and Frederick and Frances Brodribb; and those of colleagues such as Eleanor Fitzgerald and her sister, Jane Scott. More than mere likenesses, Wainewright’s portraits of the early 1840s unwittingly documented aspects of the convict system and eloquently delineated the shape of the small world in which he and his sitters moved and existed. Jane Cutmear (1834–1845) and Lucy Cutmear (1833–1854), for example, were the eldest daughters of James Cutmear, who in 1840 was appointed to the position of gatekeeper at the Prisoners Barracks on Campbell Street, where Wainewright lived. Wainewright is believed to have made his exquisite drawing of the Cutmear girls as a way of thanking their father for the art materials he kept him supplied with. Eleanor Fitzgerald (née Scott, 1809– 1846) also knew of Wainewright via the Barracks, where her husband, James, worked as the supervisor of a yard gang. James and Eleanor Fitzgerald were later employed, as superintendent and matron respectively, of the hospital where Wainewright worked and via which his access to patronage and respectability was galvanised. It was because of the hospital that Wainewright became acquainted with Edward Samuel Pickard Bedford (1809–1876), a surgeon who greatly influenced Wainewright’s colonial experience. It can be assumed also that it was through men like Bedford that Wainewright came to paint portraits of the surgeon’s brother and father; and of sitters such as Sir John Franklin (1786–1847), the lieutenantgovernor of the colony, to whom Bedford was connected both as acquaintance and physician. Frederick Brodribb (1819–1840) was another hospital associate, a trainee doctor indentured to Bedford and befriended by Wainewright, who is said to have assisted Brodribb with his studies in Greek and Latin. Frederick died on 31 March 1840, soon after Wainewright painted his portrait and that of his seventeen-year-old sister, Frances Maria.

By helpful coincidence also, those with whom Wainewright became associated at this time were often of the class of colonist – middling public servants or those of less-elevated social origins, for example – more anxious to present themselves as gentrified. Wainewright’s health underlined what was already an oddly fortuitous confluence of connection, place and position when, in early 1842, he was admitted permanently to the hospital as a patient, his ‘bodily weakness [being] such as to effectually to prevent his being employed by the Government in any kind of laborious occupation.’ When, two years later, he petitioned the new lieutenant-governor, Sir John Eardley-Wilmot for a ticket of leave, hospital staff became his most forthright defenders and supporters: James Fitzgerald noting ‘the steady and respectful manner in which he has behaved himself’ and ‘by which means he has acquired the good will and respect of the officers of the Medical Department to whom he is known’; the doctors Crooke, Mair and Clarke who considered him ‘a man of considerable attainments’ who ‘might have his talents as an artist turned to good account if he were permitted to exercise them free from the restraint now necessarily imposed upon him’; and all of them testifying to his ‘unexceptionable conduct.’

All this, of course, goes very much against the grain of what has most commonly been emphasised in the numerous writings on and accounts of Wainewright’s life and character. His vices and suspected crimes being so much more interesting than bland or established fact, Wainewright was during and after his lifetime a topic of interest for many, Charles Dickens and Oscar Wild among them. The factor that may ensure, however, that Thomas Griffiths Wainewright’s history remains an arresting one is less the image of him as a man of ‘grossly sensual habit’ and ‘the very lowest stamp’ and more that which confirms him as someone who eluded or negated his reputation sufficiently well to establish respect in a society known for its smallness, suspicions and provincialism; and who fashioned from ignobility a form of success marred only for being so sadly short-lived. Wainewright eventually gained the ‘indulgence’ of semi-freedom in 1845, after which he moved to his own lodgings in Campbell Street and set up a practice as a portraitist, charging four shillings per day for his services and creating portraits for a number of prominent citizens and families. He was recommended for a conditional pardon in November 1846 but then suffered a stroke soon afterwards. He died on 17 August 1847 in St Mary’s Hospital, established for the ‘labouring classes’ six years earlier by his friend and benefactor, Edward Bedford.