Uli Sigg first travelled to China in 1979, soon after the end of the Cultural Revolution. He entered China following the announcement of the ‘Opendoor’ policy, which was part of a larger project of ‘Socialist construction and modernisation’.

Sigg had studied law and worked as a journalist in Switzerland before taking up a position in the Schindler Group, a manufacturer of elevators and escalators. He played a key role in establishing the first joint venture company between China and the outside world – the China-Schindler Elevator Company.

Since 1979 Sigg has made countless trips to China and has lived there for extended periods, including a stint as Swiss Ambassador to China (1995–98). Over the course of three decades he has developed close friendships with a wide range of artists that have provided a fascinating perspective on contemporary China.

As a collector, Sigg recognised his good fortune to be in the right place at the right. Surprised that no person or institution was systematically collecting the experimental art being created in the wake of the ‘opening door’, he set about establishing an archive of artistic practice that was not limited by media or approach. At a time when there was no art market to speak of and few galleries, he visited artists at home and in their studios, directly acquiring works. Introductions led him to other artists and the collection grew along with his network. Sigg describes the collection as a ‘document’, and his way of ‘accessing China’. In an interview in 2008 Sigg said that his collection, which numbers more than 2200 works by some 350 artists, should ultimately repose in China, so that Chinese people may become familiar with their own Contemporary Art – which they currently aren’t. In recent years significant private collections of contemporary Chinese art have developed within and outside mainland China but none have rival the size, depth and breadth of the Sigg Collection. Sigg’s hope that his collection would one day reside in greater China turned into a reality with the announcement in June 2012 that the majority of works in his collection would be donated to M+, a private museum for visual culture that will be part of the West Kowloon Cultural District in Hong Kong scheduled to open in 2017.

How and why did you begin to collect contemporary Chinese art?

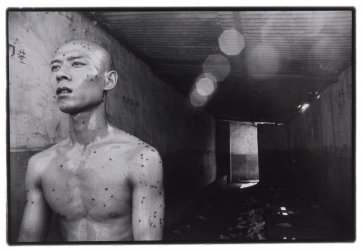

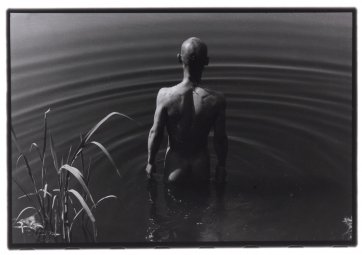

I had been collecting Western art since my student years, so when I arrived in China at the end of the 1970s, to establish what later became the first joint venture company between China and the west, it was natural that I would look around to see what the artists in my new environment were doing. I also felt that I needed another point of access to Chinese reality than what I was allowed to see at that time. I hoped contemporary art could provide a way in. But what I saw then did not seem interesting to me, looking with a western eye and coming from a region that was at the forefront of western art practice. My original intention was to collect works that pushed the boundaries, also from an informed western point of view, and that would please my personal taste. But in the early years of living and working in China, I could not find such works. It was only years later, when I felt Chinese artists had found a language of their own, that I started to collect. In the early 1990s,I realised that nobody was collecting Chinese contemporary art, beyond some random buying. That seemed strange in the case of the biggest cultural space in the world, and for what would be in hindsight a very important period. I changed my approach and decided to collect like an institution, documenting the art production of China from ‘day one’ to today, along a timeline, across all media, rather than according to my personal taste. I set out to create a ‘document’ about Chinese contemporary art that was missing in China, and was also missing outside.

It is odd that the largest and most significant collection of contemporary Chinese art has resided in Switzerland. What does this say about the field?

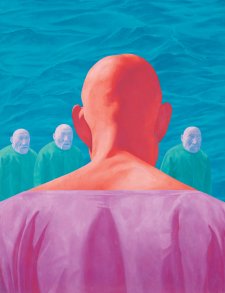

First of all the obvious question is why doesn’t such a document exist in China. The major issue here is that contemporary art can contribute to the development of contemporary culture in China, yet there hasn’t been full acceptance of this crucial point of view in China at an official level. Contemporary art is by nature often political, responding to current conditions, and can come across as being quite critical as opposed to the traditional Chinese paradigm where art is about beauty and harmony. Furthermore, the Chinese authorities are quite sensitive about how art may shape the perception of Chinese reality domestically and abroad. Therefore Chinese government institutions and museums have abstained from collecting most contemporary art production, with the exception of a narrow segment of practice, what you would call academic art. Private Chinese collectors appeared fairly late on the scene for building substantial and coherent collections. Why Switzerland? That is more random. I happened to be the first to analyse and then grab the opportunity. In hindsight it looks to be so obvious. Still, it took half of a life’s energy. And never underestimate the Swiss. There is no other country with so many significant collections per capita.

Do viewers need to understand contemporary China to appreciate contemporary Chinese art?

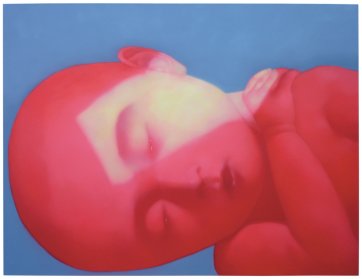

I discern two directions when it comes to the understanding of Chinese art by Western audiences. I would call one of them ‘world art’, meaning art that is accessible to anyone and that knowledge of Chinese reality or history is not necessary. This covers works that have to do with basic human subject matter, pre-conceptual things, and formalist issues. Art of this kind may or may not make any specific reference to China. Then there is a second thread of works that do require some knowledge of the Chinese context. For example, if a work deals with the government's one-child policy and its consequences for the family, and you know nothing about the one-child policy, you won't be able to understand the work in the way the artist intended. You can still like it, but for the wrong reasons.

You have close relationships with many Chinese artists. How has friendship influenced your collection?

There is a school of thought in art criticism that considers it unnecessary or even confusing to know the artist personally, believing that this may impact on the impartial judgment of the work which is the primary object of art criticism. I do not agree with this view. Collecting is my way of researching the object of my study, which is China. The works are the surface entry-point and my relationships with the artists lead me to understand what is behind this surface. In the West most collectors do not have the privilege of ever meeting the artists, since the art trade is undertaken by galleries who shield the artist from collectors unless they are big spenders, or works are acquired directly from an auction house. Contact with the artist allows me to better recognise authenticity and honesty in a work, or its absence, which for me is one of the most important criteria for collecting. That my friendships with artists exert some influence over my collecting cannot be denied, if only through the fact that you invest more in investigating the artistic thought and processes of the artists who you interact with in depth. These many friendships greatly enrich my life.

You have introduced a number of key international art world figures, such as the art historian, critic and curator Harald Szeemann, to contemporary Chinese art. Why have you done this?

Over time I have seen so many capable and interesting artists all over China, yet they were never given any attention by the outside world. It is hard to imagine that today, when Chinese artists have opportunities to show their works abroad. There was so much ignorance about Chinese contemporary art in the Western world. The gatekeepers to the mega-events such as Venice [Biennale] and Kassel [Documenta] and to the major institutions came exclusively from the West. That is why I used to call what we saw in these prestigious exhibitions ‘NATO Art’. The art world was ruled by the same nations that used to form that power block of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation – the USA and mostly Western European countries which used to dominate the old world. To somehow tilt this lopsided powerplay by the Western mainstream art world figures more towards China, I felt there was only one remedy: to give these gatekeepers exposure to Chinese art. As a tool for this purpose I established the Chinese Contemporary Art Award.

You created the Contemporary Chinese Art Award and in 2007 created the CCAA Art Critic Award. Why did you do establish these awards and what was the response?

I set up the Contemporary Chinese Art Awards up in 1997. It has since become an institution of significance for the Chinese art scene. I had two things in mind: to lure important international curators to Chinese art; and to stimulate debate within China as to what constitutes meaningful contemporary art and what does not. As a consequence Chinese artists have had exposure to the prominent art juries, and through highly influential individuals like Harald Szeemann, Alanna Heiss, Ruth Noack, Chris Dercon and Hou Hanru, to name a few, have gained opportunities to show to new audiences abroad, for example at the Venice Biennial in 1999. In 2007 I established the CCAA Critic Award for independent art criticism, to bring this important activity into public focus. The market has dominated the debate on what is considered meaningful art, and unlike in the west is not balanced by sufficient independent institutions and critique to allow for a more informed discourse. CCAA has a lot of potential. I can see it assuming a position similar to the Turner Prize. Since 2007 other awards have mushroomed in China, but I question their academic value and independence.

In the early years, immediately after I established the Award, there was criticism of me, being a foreigner, assuming the authority to make a value judgment on Chinese art. I had to explain how my general knowledge and expertise regarding Chinese society had been gained through my experience in China in business, politics, and through my interface with maybe more artists than anybody else during those years, and more importantly, that I was just one of several jury members. This explanation seemed to counter a deeply rooted intuition, that the Award was intended as yet another Western or individual powerplay. These criticisms have subsided. From very early on I voiced my desire to share this platform with others and ultimately make it a Chinese owned initiative. Deliberate and reasoned debate on what is meaningful art and what is not should be shaped from within China.

How do you see contemporary Chinese art within a global context?

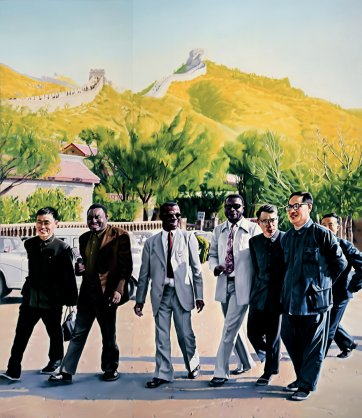

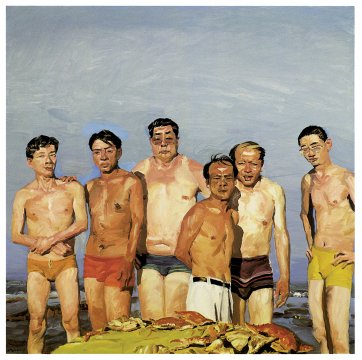

The differences between Chinese and Western art have changed with time. In the beginning, after 1979, Chinese art was politically charged, much of it created in conflict with and rubbing up against the repression of the political system. This art was distinctly different from that produced elsewhere. It documented and reflected on Chinese reality and was made with very limited interaction with the outside world. The situation is very different today. Contemporary art has risen out of the underground and even made it into popular people’s magazines. The former ‘enemy’ creating resistance and tension has largely disappeared and the pressure of the art market is mounting. Artists now lead lives that in many ways are comparable to their peers in London and New York, with access to the internet, books, catalogues, and to travel. This has led to a different mode of art and art production, which may come across as looking more ‘international’ and less ‘Chinese’ than in the past. And so, right now, before our own eyes, we see the merging of these two streams: of a Chinese contemporary art with a distinctly different viewpoint and language, joining with what I call global mainstream art. The big question is, what will happen in this merging of the Chinese and the global mainstream? Will Chinese art have an impact on this global mainstream or will it simply be swallowed up and become an endangered species?

You have displayed works from your collection in a number of countries around the world, including now Australia. What have you hoped to achieve through these exhibitions?

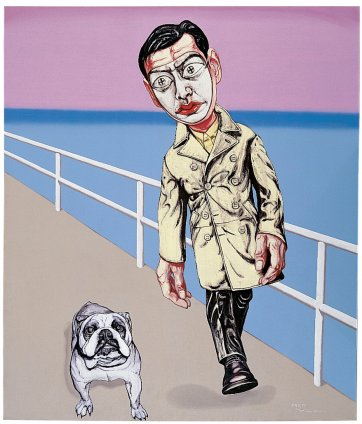

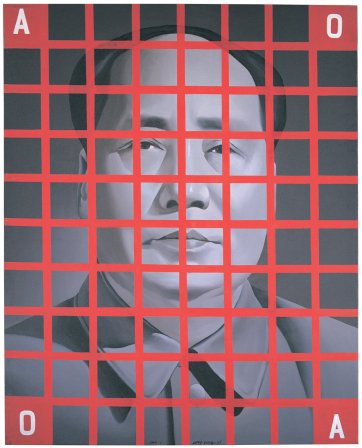

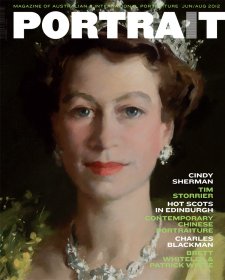

The first exhibitions were mainly overviews and very much in line with my self-imposed mission to make a wider audience aware of the width and depth of Chinese contemporary art. They produced large turnouts and surprise – surprise as to the variety, intensity and quality of Chinese art production. Recent institutional demand has been for exhibitions that explore specific topics – such as Go Figure! Contemporary Chinese portraiture for the National Portrait Gallery, or Chinese landscape painting which was recently held in Switzerland. The depth of the collection allows for such vertical drills. I see the 2200 works as material that can be mined in many different directions. I also want to provide the interested public with another access point to China - through its contemporary art, one that is more tangible than digitally transmitted images in our media. Exhibitions allow us to better comprehend the complexity and diversity of this world-power-to-be.