For more than ten years, the National Portrait Gallery had only one work by Charles Blackman: The family (Judith Wright, Jack McKinney and Meredith McKinney). Painted in about 1955, the work had been in private collections for more than four decades before Barbara Blackman, long-divorced from Charles, heard it was for sale.

She purchased the painting of her dear friends for the young institution in 2000. Now, quite suddenly, it has come into flower amidst other portraits by the artist. The vital new context for The family has come about through a combination of purchases, gifts and loans to the Gallery over the past twelve months.

As a boy, the painter Charles Blackman OBE (b. 1928) was better at drawing than he was at anything else. Having left school at thirteen he worked for the Sydney Sun while studying art by night. After a few years’ drifting between Sydney and Brisbane, he forged a bond with Barbara Patterson (b. 1928), a writer whose first poem had been published in the ABC Weekly when she was fifteen. She was the youngest member of Brisbane’s avant-garde writers’ group, ‘Barjai’ which included Judith Wright (1915–2000). Barbara Patterson began to lose her sight as a teenager, and soon after she and Charles moved to Melbourne and married in 1951, she was declared legally blind. Living on a combination of her inheritance and her blind pension, Charles began to paint in earnest. Barbara also brought home significant bacon through modelling: said to have a repertoire of two hundred poses, she was portrayed many times by Fred Williams, and also by John Brack. Blackman, who rarely worked with a model, had to accustom himself to working in isolation in the loft of the coach house they rented in Hawthorn.

Some years ago, a Sydney collector, Paula McLean, was looking for a Blackman painting as a birthday present for her husband, Robert. Intent on a picture of schoolgirls – subjects of Charles Blackman’s first major series – Paula found herself drawn to the intensity of The chase instead. In particular, she was curious about the symbolism of its two flowers, cat and scootering child. The McLeans visited the National Portrait Gallery in 2009, and two years later, when they sold their family home to move somewhere smaller, they felt it was the right time for their Blackman to move somewhere bigger, enhancing the Gallery’s collection of midtwentieth century self portraits.

The chase is one of several self portraits Charles Blackman painted in Melbourne in the early 1950s. Barry Humphries once described Blackman as the Scobie Breasley of the easel, as diminutive and thin as a jockey; he has probably been described more than once as elfin. That is to say that in this self-portrait, the whimsicality of the reversed hands and goggly eyes notwithstanding, Blackman presents a likeness that is not as exaggerated as might be supposed. Felicity St John Moore, an authority on Blackman, chooses to concentrate on the symbolism of the work: ‘The artist portrays himself with arms crossed and a flower in either hand. One flower is alive, the other is dead. Together with his expression of adolescent yearning, the imagery suggests an either-or choice between creation and spiritual death … The idea of clear choices facing a person at the moment of loss of adolescence, which is found in both Rimbaud and Gide, reflects Blackman’s immersion in French literature at this time.’

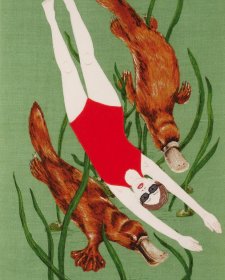

Charles Blackman had never been much of a reader before he met Barbara. He first heard Alice in Wonderland on a talking book borrowed for her from the library. In 1956 and 1957, he painted more than thirty works inspired by the story, with his wife the model for the gentle, commonsensical girl of the paintings. Judith Wright, who wrote a catalogue essay for an exhibition of the Alice works in 1966, had encouraged Barbara’s literary avidity. In her book Glass after glass Barbara recalls being magnetised by Wright and her husband Jack McKinney, telling of how she ‘breathed their booklined air and plunged into their bottomless questioning … I loved their wordiness and their quirky humour. They read me Jung.’

The family is not a comfortable portrait; its subjects appear anguished and alienated, and its flowers add no cheer to a landscape as bleak as the slopes of Stromboli. But then, though Wright and McKinney were happy together, they were serious people. They came together at the war’s end, when they were supposed to be euphoric; but they felt misgiving.

By her mid-twenties, Judith Wright had come to think that there was something far more deeply wrong with humankind than the New World Order, capitalism, communism or socialism could fix. In her memoir Half a Lifetime she paints a picture of her young self unable to find a path forward. Enter Jack McKinney: some thirty years older than she was, he had written an article she didn’t understand, but there was something about its ‘unashamed, even naïve’, focus on the future that pulled at her. McKinney was a ‘wild philosopher’ with remarkable blue eyes; though he had been schooled at Scotch College in Melbourne, he had taken early to the road and had ended up in Queensland a failed farmer, a war invalid and a pensioner. He had a wife and children whom he saw intermittently.

He was totally disconnected from academic departments of science, philosophy, literature or politics but his writing sought nothing less than to deconstruct all these disciplines. In short, when he and Wright met, McKinney was rethinking the development of the western world and its entrapment in language, with no qualifications, support, money or acceptance of any kind.

Wright, as it happened, was working as an administrator at the University of Queensland, and as an ‘insider’ decided she could help by getting hold of books for Jack. By way of courtship, they ‘began a quest taking us through the available reference books on quantum theory, Bertrand Russell’s The History of Mathematics, philosophical works and the rest.’ With money she had saved, Wright and McKinney moved to a hut at Tamborine in the Gold Coast hinterland. It was the beginning of 1946, a few months after the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Characteristically, Jack’s priority was to learn about the quantum physics that underpinned the atomic bomb. The couple called the house Quantum because the ramifications of the bomb were always on their giant collective mind; but also because the word denotes the smallest possible quantity of something that will suffice for a given purpose. The name, then, encapsulated both their anxiety about humankind, and their contentment with each other in their sparely-appointed home.

Having become a new father to Meredith, Jack also became a father-figure to Barbara Blackman. Claiming that ‘the next development of knowledge will be the responsibility of understanding our emotions’ McKinney is said to have encouraged Charles, too, to engage honestly with his own feelings. The family recalls a winter’s day when the Blackman and Wright/ McKinney families picnicked at Cedar Creek near Tamborine. The painting incorporates the motifs of schoolgirl and flowers that were to become hallmarks of Blackman’s work of the 1950s and 1960s. Indeed, the critic Thomas Shapcott suggested in the 1960s that it was Tamborine’s place in the Queensland cut flower industry, as well as Barbara’s mother’s Brisbane house with its garden and bouquets, that awakened Blackman to the potential of bringing together faces and flowers – the combination later identified as ‘commandingly and decisively Blackman.’ Blackman himself said that when he first started painting flowers, ‘they were very very floral and “flowery” in a kind of way, but still a bit angst-y, a bit Funeral funeral, something like that, as well as being colourful’. The critic Gertrude Langer commented that his flowers often ‘seem like souls of flowers’; Blackman, for his part, has spoken of his attempts to capture ‘that particular kind of frailty and sensitivity which people have in relation to flowers’.

Blackman’s flowerless, starkly moving portrait of Judith and Barbara was offered to the Gallery on indefinite loan from Sydney collectors John and Joanna McNiven early this year. The McNiven portrait emits a soft neon glow deriving from the thin layer of blue paint laid onto thick yellowish-brown paper. The paper is left largely bare on the faces and skin of the two women – at this stage of his career, Blackman had to economise on paint where he could. Although the theme of close relationship, conveyed by gesture, is common to many of Blackman’s strongest ‘big, tough and tender’ works of the early 1960s, what critic Ray Matthew wrote of the Alice figure – that ‘the head, adult and triumphant even in perplexity, sits on a child’s body’ – applies equally to the heads on the figures in this work. Indeed, when it came up for auction at Sotheby’s in Melbourne in 2008 it was titled Two schoolgirls. Together, however, before the auction day, Felicity Moore and Barbara Blackman confirmed that it was a painting of Barbara in profile under a hat of Judith’s, with wispy hair and a luminous eye, her hand, resting on Judith’s blunt bob, splaying protectively over her friend’s deaf ear as her own blind eyes search out her face. The gesture makes poignant sense of the identification. Nonetheless, Moore suggested recently that the work had probably been painted from memory when the Blackmans were staying at the McKinneys’ Queensland house but Judith and Jack were away.

It has often been observed that Blackman’s paintings and drawings, including most of his portraits, spring from memory and imagination, rather than observation. It is thus very difficult to answer the question of whether any of his works is a portrait, or whether his portraits portrait were painted from life, in the straightforward sense of the phrase. Ray Matthew wrote in 1965 ‘Alice with her great absorbing eyes, her calm sense in an absurd world is recognisably his wife (always from memory never from life)’. Matthew refers to his ‘incessant’ painting of Barbara, but Blackman told the writer Thomas Shapcott in 1967 ‘I use the word Barbara, because it is simpler, it’s not necessarily true, you understand …’ In conversation with James Gleeson, Blackman mentioned that he once made a portrait of Barry Humphries’s former wife without even meaning to: ‘I used to talk to her every morning before I went to work and finally when she came around she said, “You have painted a picture of me, Charles”.’

One portrait that Blackman certainly painted from life was that of the Melbourne restaurateur and gallerist, Georges Mora, purchased by the Gallery in 2011. It dates from 1956, when Blackman was alternating between painting in silent solitude, and slaving hectically in Melbourne’s hottest new dining destination, the Eastbourne Café.

Georges Mora (1913-1992) was born to a Leipzig Jewish bourgeois family of Polish descent. He worked for the Resistance in Paris before migrating to Melbourne with his pretty French Jewish wife, Mirka Zelik, in 1951. At first, he eked out a living managing a matzos factory. The Moras settled in Melbourne just as Blackman began to gain support from the art patrons John and Sunday Reed, enabling him to produce a decent body of work. As soon as Mirka Mora saw Blackman’s schoolgirl series, she resolved to exhibit them in the tiny flat she and Georges were renting at the Paris end of Collins Street. It was the beginning of the Moras’ life as gallerists; and Barbara Blackman recalled that the Moras’ quickly became ‘the place of exhibitions, meetings, parties, dramatic moments, tableaux vivants, plots, confrontations, improvisations, diagnoses and prognostications … vortex of our marvellous lives.’ In the mid-1950s, Georges and Mirka purchased Melbourne’s first espresso machine for the Mirka Cafe (the first Melbourne café with outdoor seating) which showcased the work of contemporary artists. The Eastbourne Café, renamed the Balzac, became the first Melbourne restaurant with a licence to serve liquor after 10pm. For these and other ventures, including the Tolarno Hotel in St Kilda and Tolarno Galleries in South Yarra, Baillieu Myer is said to have credited Georges Mora as ‘a man who made Melbourne into a city’. Mora and Blackman came from very different backgrounds, but they were close friends. Of the several portraits Blackman painted of Mora, this is the tenderest tribute; it is, in fact, Blackman’s most straightforward painted portrait. Yet there’s more: Barbara Blackman indicated recently that as Blackman and Mora looked remarkably alike, his several portraits of Mora are also generally acknowledged to be Blackman’s most convincing ‘self portraits’.

Barbara and Charles Blackman lived in London from the beginning of 1961 to the beginning of 1966, when they established a base in Sydney. From 1973 they supported the establishment of an alternative senior school, Chiron College, in Birchgrove, Sydney. Over the coming years she wrote, he painted, they travelled, she set up a printing press, he travelled alone. Although she was for many years the muse and model for his work, Blackman rarely represented Barbara ‘straight’. Often, in pictures such as the two assured drawings acquired by the Gallery in 2010 – one made in 1969, one in 1976 – a shadow falls across her face. Over those decades, too, the light went out of the Blackmans’ relationship. In June 1978 Barbara resigned in writing from their marriage, giving two weeks’ notice, the resignation to take effect on the couple’s twenty-seventh wedding anniversary. At about that time, Charles painted her a bouquet of fifty flowers for her fiftieth birthday. In subsequent years the one-time fruit picker and dish pig became one of very few Australian artists to live to see one of his paintings sell for more than a million dollars.

Jack McKinney’s The Structure of Modern Thought was published in 1971, some years after his death. Judith Wright reflected that ‘through the years before its publication it had accompanied me as a sort of guarantee that meaning was a human creation guaranteeing the significance of human life. It was as much his sheer tranquil existence as his work that supported me through what I thought of as “the rest of my life”’, she wrote.