Martin Schoeller the German-born New York-based photographer strips away the trappings of celebrity seeking the person beneath.

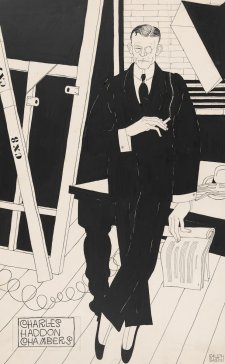

Australia is recovering from MacKillop fever, the enthralling moment of 17 October 2010 that we all shared as Sister Mary MacKillop was canonised Saint Mary, Australia’s first saint. As Adelaide’s archbishop Philip Wilson enthusiastically described it, Mary finally arrived in the first grade and is playing the premiership league.

We were elated when Mary was sainted and we teetered, if only for a few days, on hysteria when Princess Diana died. The adulation for celebrity and the craving for connections with super humans, whether their field of achievement is religion, sport, politics, music or acting, is immense and deep seated. The cult of celebrity is alive in Australia and Who magazine is its bible. Mass media has increased the power and fascination of celebrity but shows little regard for virtues or talents – its enough to be beautiful, notorious or even just familiar. Celebrity is as much a product as a person. Perhaps the contemporary curiosity about celebrity lives comes out of an anxiety and need for relationships in an increasingly anonymous society. When village culture was replaced by the global village, society lost much connection and intimacy. We watch television to empathise with the dramas of actors as our own connections diminish. Today our family is the cast of Modern Family and the TV is not in our living room, we are in its. While celebrity culture might be based on the need for drama and spectacle, the loss of belief systems (Mary MacKillop not withstanding) is also part of this phenomenon. The cult of celebrity fills what Jean-Paul Sartre called the 'God-shaped hole in our consciousness'.

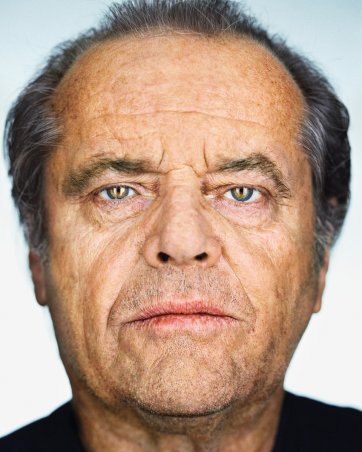

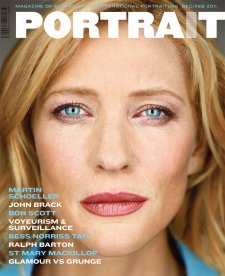

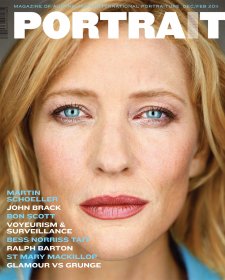

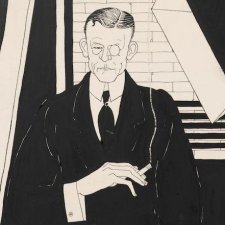

New York-based photographer Martin Schoeller at first glance appears to be an acolyte of the cult; he is employed by some of the highest circulation magazines – the New Yorker, Entertainment Weekly, Rolling Stone, GQ, Esquire, and Vogue – to record the faces of the famous. He has made astonishingly graphic images of Bill Clinton, Cate Blanchett, Marilyn Manson and many other notables who make up the canon of contemporary fame, secular saints in the cult of celebrity worship. Schoeller has become famous himself for his powerful portraits but his singular photographic technique simultaneously celebrates and subtly undermines celebrity.

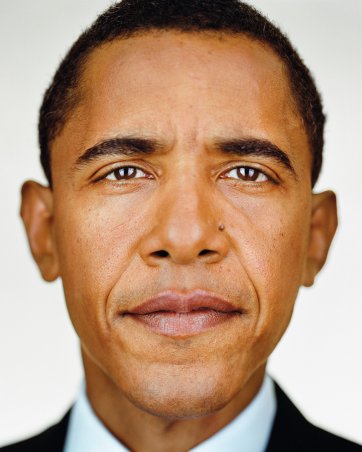

The National Portrait Gallery presents forty-eight monumental portraits in the exhibition Martin Schoeller: Close up, his first Australian exhibition. Schoeller is best known for his Close up series of celebrity portraits. He frames his subjects, Bill Clinton, Angelina Jolie, Jack Nicholson and numerous other well known figures, to exclude context and show only the face in extreme close up. Under the unflinching scrutiny of his lens, the faces of actors, politicians, musicians and unknowns, are transformed by the wealth of unfamiliar detail to expose the complexity of the human face. Face becomes topography, an undulating landscape of hills, valleys, crevasses and plains marked by pores, hair and skin textures. Schoeller uses his close up technique as a way of levelling differences between individuals. His portrait of Barack Obama, the President of the United States, is framed no differently than that of a tribal man from the Amazon region of Brazil. Without a background to provide clues about social status, the uniform presentation of each head places each in a position of equality, a democracy of effect that encourages comparison.

Schoeller’s even-handed treatment of his subjects derives in part from his early admiration for German Conceptual artists Bernd and Hilla Becher, who photographed post industrial monuments – cooling towers and mine tipples – in an uninflected documentary way. The Bechers, said Schoeller, ‘inspired me to take a series of pictures, to build a platform that allows you to compare.’ Schoeller’s work also shares affinities with fellow German photographer Thomas Ruff, also known for his bold portrait heads but is informed by his own egalitarian beliefs. ‘The pictures in my Close up series have all been taken from similar angles and with the same equipment, but here I have tried to bring out personality and capture individuality in a search for a flash of vulnerability and integrity.’

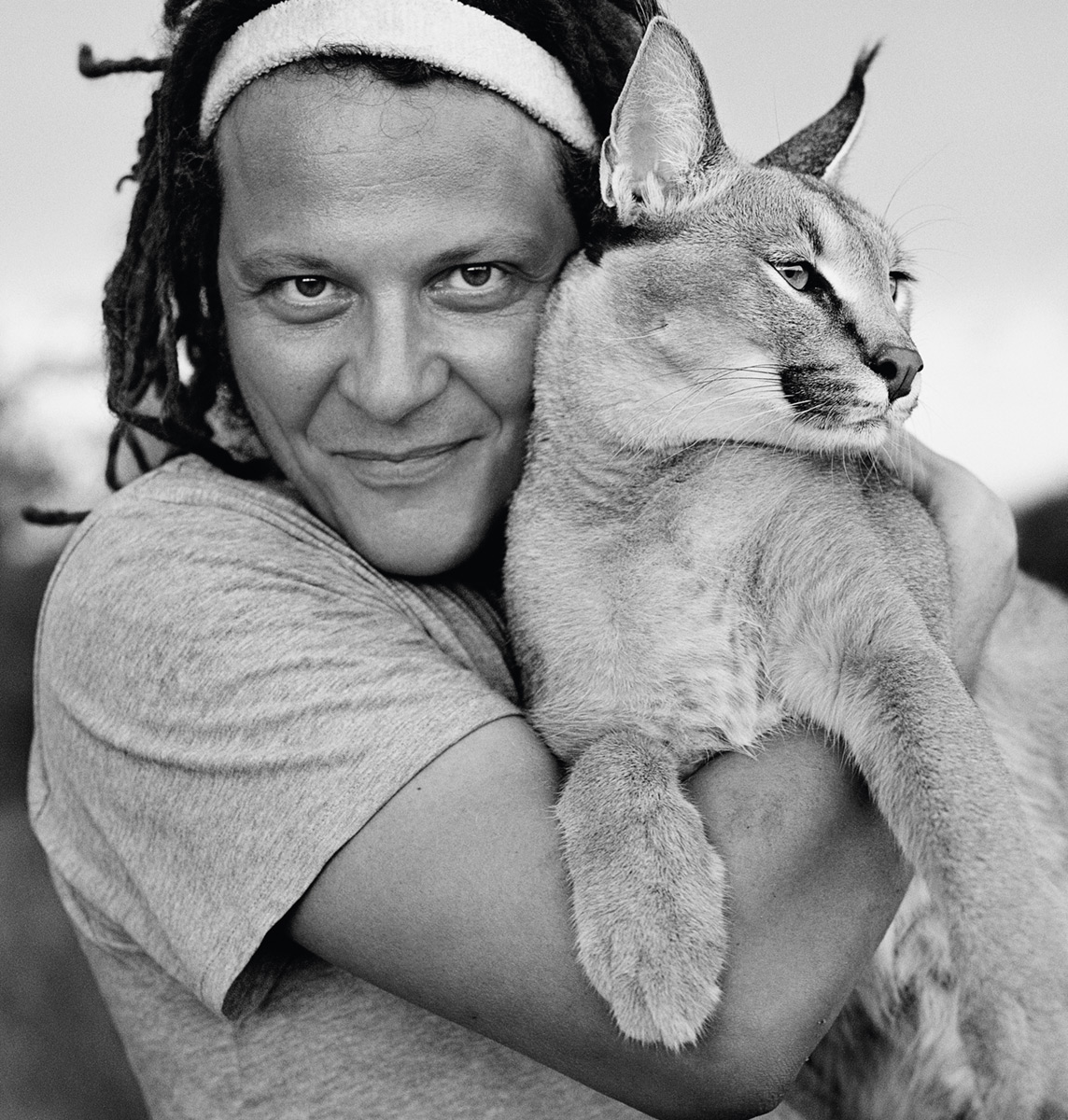

Born in Munich, Schoeller moved to New York in 1993, first working as an assistant to Annie Leibovitz before striking out on his own. Schoeller worked for a variety of prestigious journals and has exhibited his photographs in the US and abroad. Speaking about the portraits in Close up, Schoeller suggested that his technique was built on intimacy: ‘It’s a reflection of my personality that I feel comfortable being close to somebody. I always felt that it really was the most essential part about a person, stripping away the clothes, stripping away any backgrounds, really focusing in on that person.’ Schoeller new work has taken him away from closely cropped heads to a new series, this time of female bodybuilders. Like the Close up faces, the women confront the viewer, challenging expectations of identity.