Conceived by Sandra S Phillips and co-curated with Tate curator of photography Simon Baker, exposed examines photography’s role in voyeuristic looking from the nineteenth century to the present.

In the 1870s, facilitated by advances in technology, the camera moved out of the studio and into the street. With a small device in hand, photographers found it relatively easy to catch someone by surprise or completely unawares; by the 1880s cameras would be disguised as tie pins, hidden in canes, or found peeking out of the heel of a man’s shoe. Such equipment was used mostly by nonprofessional photography enthusiasts, who quickly became a nuisance as they preyed on their unsuspecting target – the idea of hunting is retained in the way we talk about “shooting” pictures.

The compact and portable camera of the 1930s and 1940s was the 35mm Leica. Because of its novel size it was also less conspicuous, and the right angle viewfinder attachment allowed photographers to shoot subjects surreptitiously while facing away. With this advantage, photographers such as Walker Evans, Ben Shahn, and Helen Levitt made pictures of their subjects caught unawares on crowded streets. Evans’s pictures demonstrate a continuous fascination with invading the privacy of those he photographed, subjects ranging from people sleeping on city streets to the intimate living spaces of poor farmers in the American South, culminating in his hidden camera portraits of passengers lost in thought on the New York subway.

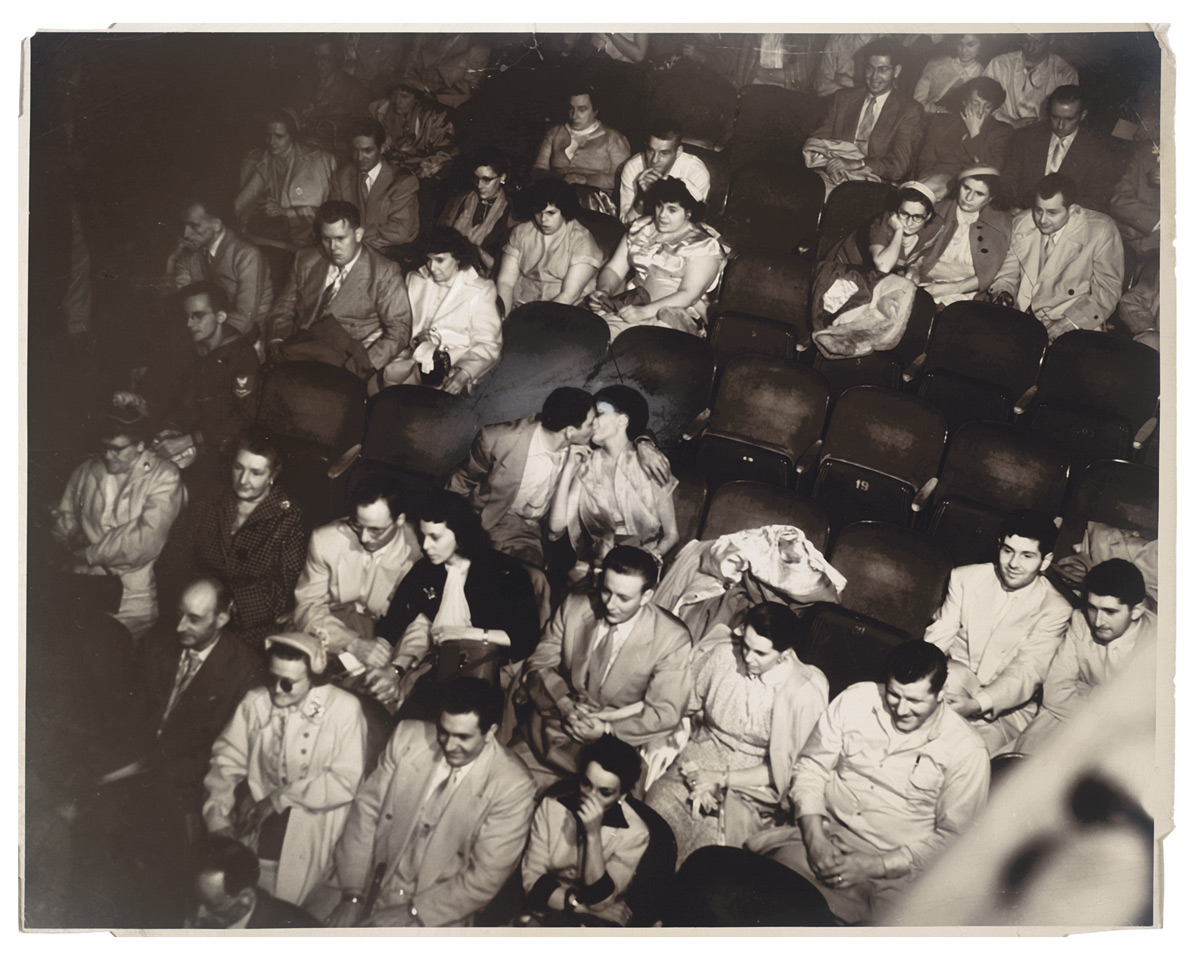

Weegee’s photographs of lovers stealing intimate moments in public places display a similar desire to look voyeuristically at the forbidden. The photographer Paul Strand once described Weegee as “a specialist in the drama of what most of us neither sees nor wants to see.” Indeed, Weegee was a master of sensationalist photography; most of his photographs depicted gruesome murders and other crime scenes, helping him earn his nickname – a reference to the Ouija board – for his seemingly uncanny ability to arrive at the scene shortly after the crime occurred. Weegee’s photograph of the audience in the Palace Theater taken from the rafters with infrared film, suggests that the most interesting drama in the theater takes place off screen.

The 1960s saw these precedents revived and transformed in a new kind of documentary photography. Using use an extra wide lens, so that people on the edges of his photographs wouldn’t have realised they were in the frame, Garry Winogrand embraced not only what was directly in front of his lens but also collateral information on the periphery. Winogrand’s lightning-fast snapshots of street life demonstrate that photography works faster than the eye to capture a split-second slice of real life.

While portraits of the famous had always existed in painting, it was photography that invented modern celebrity culture. The development of the small camera and fast film allowed unposed pictures of well-known figures to be made quickly and inexpensively. The perfection of the halftone process facilitated the ease with which such pictures could be reproduced in newspapers, initiating a culture of seemingly limitless pursuit and dissemination. The tension between the photographer and the famous person – who desires both privacy and publicity, and whose persona depends on a kind of notoriety – is often evident in the photograph. The first deliberate construction of a celebrity persona through photography was that of the extravagant nineteenth-century beauty the Countess of Castiglione, who orchestrated some four hundred self portraits depicting herself in the role of seductress, actress, even courtesan. These pictures anticipated the blurred distinction between public and private, reality and fantasy, that is the principal territory of celebrity photography today.

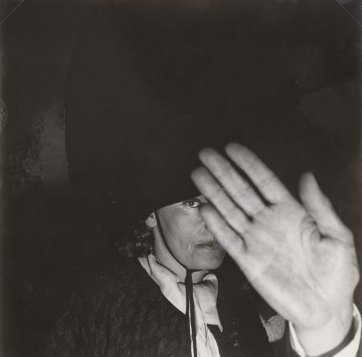

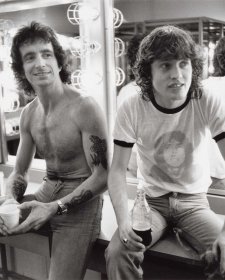

In the years following World War II, paparazzi photographers such as Tazio Secchiaroli and Marcello Geppetti met the growing demand for pictures of film stars. Later, Ron Gallela’s aggressive and intrusive efforts to photograph Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s every move would cease only when a court intervened on her behalf. Secchiaroli, who is recognised as one of the original paparazzi, photographed actress Anita Ekberg and her husband Anthony Steel as they left a popular nightspot in Rome in 1958. Secchiaroli’s career was defined by his discovery that newspaper editors would pay far more for “surprise” photographs of celebrities than posed ones. In pursuit of his subjects he would follow celebrities through Rome on his Vespa, frequently staging confrontations with them to get the candid pictures he desired. Though the ethics of this kind of “assault journalism” are highly contentious even today, Secchiaroli maintained an unwavering commitment to it throughout his life. As he explained: “We photographers were all poor starving devils and they had it all – money, fame, posh hotels. The doormen and porters in the grand hotels gave us information tips – you could call it the fellowship of the proletariat.”

Contemporary photographer Alison Jackson underlines the simultaneous absurdity and appeal of photographs of celebrities. Through her staged photographs of celebrity lookalikes, Jackson has taken the candid picture to an extreme, picturing her 'celebrities' in their most intimate moments. These mock-paparazzi photographs remind us of our insatiable desire to see the foibles of people whom we know in only the most remote way.

Shizuka Yokomizo’s richly unsettling photographs investigate the idea of voyeuristic seeing with the subject’s consent. For this series she wrote letters to strangers, asking them to pose for her by appearing in the windows of their homes at a specified time (those who declined to participate could draw their shades). Even for those who did participate, Yokomizo remained an anonymous presence, appearing only briefly and as little more than a shadowy figure outside their windows. In Stranger No. 1, a young man appears casually in his shorts, and talks on the phone as if he is confident with his casual appearance in the resulting image. Others, such as the woman in Stranger No. 2 appear more guarded, uncomfortable with the act of inviting so public a gaze into the privacy of their homes.

Most of the pictures in Exposed, however, were made without their subjects’ knowledge. Many were taken quickly and discreetly on the street, or simply while peering down from a window, protected from outside observation. Voyeurism remains a potent, widespread, yet generally unacknowledged aspect of photography, practiced by artists, amateurs, professionals, and spies. By examining the ever-present eye of the surveillance camera of today and the nineteenth-century street photographer spying on his subject with a concealed camera, Exposed explores how our definitions of respect, vulnerability, and security have shifted over time, altering our understanding of what it means to look and be looked at.