Joanna Gilmour profiles expatriate Australian watercolourist Bess Norriss Tait whose expert miniatures made her a sought after portraitist in her day but whose reputation was ultimately overlooked in favour of the larger scale work of her contemporaries.

It’s an accepted truth that miniature painting was among those professions that suffered most from the rise of photography in the mid nineteenth century. Cheaper, quicker, and supposedly able to deliver a loved one’s likeness more truthfully than painting, photography took the place previously occupied by miniatures in the marketplace for small, portable portraits and by the turn of the century had little competition as the predominant format for this genre. Yet it was around the turn of the century also that – whether in rebuke or response to the one-upmanship of the photograph – there was something of a resurgence in miniature painting by artists who resisted the art form’s diminished status and embraced instead the challenge of fashioning precise and tiny portraits from the slippery medium of watercolour on ivory. Australian artist Bess Norriss Tait was at the forefront of this revival.

Bess Norriss Tait was born in Melbourne in 1878 and had her first drawing lessons, aged ten, from Jane Sutherland, a painter perhaps best known for her association with the artists grouped together as the Heidelberg School. Norriss Tait recalled in an interview in Art in Australia in 1922 that Sutherland was thorough in her instruction in drawing from life and in her advice to ‘observe accurately the reproductions of the works of the old masters’. Norriss Tait was fortunate too in having a family that was appreciative and encouraging of her work and – as was the case with many of her women artist contemporaries – a family seemingly open-minded enough for her to pursue art as something other than a girly accomplishment. Consequently, she became a student at Melbourne’s National Gallery School and under the tuition of Frederick McCubbin and Bernard Hall between 1897 and 1901 began exhibiting watercolours and miniatures with the Victorian Art Society. It was at the instigation of one of her first patrons that she sent samples of her miniatures to a London expert, Dr George Williamson, who recognised the strength and originality of Norriss Tait’s work and advised her to come to England. She later recalled that Williamson wrote such ‘encouraging and critical letters’ that, like many young Australian artists, she was unable to resist the lure of Europe. For six years she ‘scraped and saved’ for her fare, finally leaving Melbourne for London in 1905. Once there, she was introduced to potential patrons and influential critics and quickly attracted a fashionable clientele. She studied at the Slade School, became a member of the Royal Society of Miniature Painters, and in 1908 achieved the first of her many inclusions in exhibitions such as those of the Royal Academy and Paris’s New Salon.

Throughout the decade following her arrival in Europe, Australian newspapers noted her inclusion in these and other forums alongside compatriots like Bertram Mackennal, Emanuel Phillips Fox, George Lambert, John Longstaff, Arthur Streeton and Thea Proctor. By 1910, the Sydney Morning Herald was declaring her to be ‘universally accepted as a miniature painter of exceptional talent’ and, when profiled in Art in Australia twelve years later, she was announced as being ‘in a class by herself’ among miniature painters in London. This stature, however, has since become somewhat difficult to discern. Bess Norriss Tait was hardly alone as an Australian artist who permanently exchanged the provincial world of home for the prospects promised by London and Paris but, in comparison to her peers, she figures rather slightly in the art histories of her homeland. While not without the grace or elegance of contemporaries like Fox, Proctor and Rupert Bunny, Norriss Tait’s work has been out-scaled, literally and figuratively. It is as if her place alongside them has been affected less by her decision to live her professional life overseas and more by her being a leading practitioner of an art form sometimes deemed too ephemeral, too twee or too feminine for serious attention.

Bess Norriss Tait’s success as a portraitist was helped by her place within belle époque London’s creative establishment and her work – distinguished by what one critic in 1924 described as her ‘dainty, wistful talent’ – offers a survey of the social circles she moved in and their mood of ease and refinement. Her friends included figures such as English sculptor Francis Derwent Wood, himself an associate of Australians like Lambert, Streeton, and Tom Roberts, among others. Norriss Tait’s husband, James Nevin Tait, whom she married in London in 1910, was the UK representative of the Australian theatre company JC Williamson Ltd and the manager of Australian engagements for performers such as Percy Grainger and Ada Crossley. Norriss Tait’s patrons included Queen Alexandra and the American collector J Pierpont Morgan. And among her subjects were her Chelsea neighbour, Lydia Russell, the wife of Sir Walter Russell (a professor at the Slade and later the Keeper of the Royal Academy collection); Rose Grainger, mother of composer and concert pianist Percy; Australian painter and Nellie Melba’s niece, Helen Lempriere; divas Dame Clara Butt and Emma Calvé; and English violinist Marie Hall.

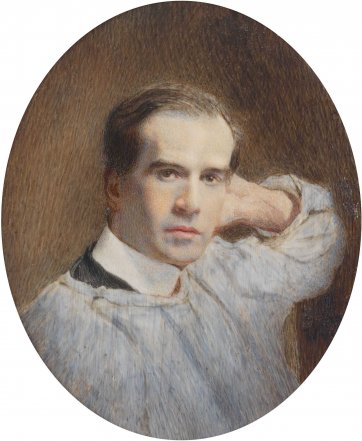

But the charm of Bess Norriss Tait’s portraits easily serves as a diversion from the boldness and inventiveness that characterised her style. ‘I fear’, Norriss Tait stated in 1922, ‘that I have little sympathy with the superficial, pretty, chocolate-box miniatures which one so often sees’ and her portraits – as sweet and as peachy as they may seem at first glance – accordingly made a distinct departure from tradition. In contrast to other miniaturists whose method, typically, was to discipline watercolour into a tight rigour of stipples, Norriss Tait’s method – influenced by artists such as James McNeil Whistler – was one which mimicked the qualities of her medium with its energetic, fluid and expansive gestures. As critics in London newspapers in 1913 put it, Norriss Tait’s portraits were ‘painted with spirit’ as well as being ‘unconventionally composed and full of character, but not the smiling character usually associated with miniature.’ Instead, Norriss Tait’s portraits were, according to one observer, ‘miniatures in size only’ and marked by their ability to express, sometimes in minute and delicate scale, a rare sense of a sitter’s personality: ‘when working at even her smallest pictures she feels that there are bones and muscles beneath the skin’, effecting a depiction of her subjects as ‘living, breathing humans, not mere pretty dolls.’

Such statements echo Norriss Tait’s own words on her approach to painting and her belief that a good miniature ‘should lose nothing by comparison’ to a work on canvas: that ‘drawing, structure and colour should be truly comprehended, even on the smaller scale.’ The deftness with which Norriss Tait comprehended the likenesses of her subjects, whether on ivory, card, or paper, demonstrates that for her and other artists who worked in this manner, watercolour and miniature painting were substantially more than cutesy practices adopted for pleasure by amateurs. Norriss Tait was one of a number of artists who chose to pursue the medium professionally and who seem to have welcomed the challenges it presented. Predominant and most highly regarded among these were a number of women, including Norriss Tait’s compatriots Bernice Edwell and Bessie Gibson – artists akin to Norriss Tait in their practice as well as in their less lofty positions in the records of Australian art.

Bess Norriss Tait’s 1909 self portrait is only the fourth work by the artist to enter a major Australian public collection. Painted in London, it illustrates Norriss Tait’s deftness and wit and exemplifies her originality of style – an originality evident when comparing Norriss Tait’s work to other miniatures of the era, such as Bessie Gibson’s portrait of another Europebased Australian, sculptor Harold Parker. It was Norriss Tait’s style that made her a unique and sought-after portraitist in a medium that enjoyed a vigorous revival in her lifetime, but that has remained largely overlooked or unable to compete with the bigger efforts of some of her associates. The acquisition of Bess Norriss Tait’s Self portrait by the National Portrait Gallery might thus go some of the way towards reinstating her to the company of Australia’s most successful expatriate artists and to affirming her so-called ‘dainty talent’ in its place amidst the large and lauded reputations of her contemporaries.