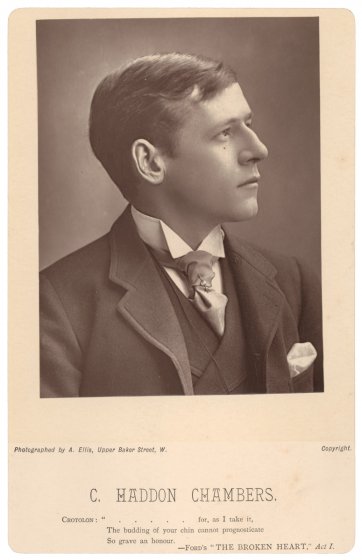

One fine day in 1902 Nellie Melba motored up to Hugh Ramsay’s Paris studio with her lover, who was keen to introduce the prima donna to the young painter’s work. Like them, the artist was an Australian who had headed for the glittering capitals to test his mettle. Melba is today widely known as Australia’s most brilliant fin-desiècle expatriate; and Ramsay enjoys an unassailable reputation, at least amongst connoisseurs of Australian art. By contrast, Melba’s companion that day – and for some eight years – Charles Haddon Chambers, is today virtually unknown to us. But he was anything but a nonentity at the time; and further, he remains Australia’s most successful playwright and dramatist. From 1888 to the end of the First World War, his plays were staged in the West End and New York. Handsome, elegant and a scintillating conversationalist, he was courted by society hostesses and prominent in club life.

Charles Haddon Chambers, born in Petersham in 1860, grew up in Sydney, where his father worked in the Colonial Office. Leaving Fort Street school at thirteen to help support his family, he worked as a clerk and then, for two years, as a boundary rider. Having travelled to Ulster and London, he returned briefly to work in Sydney before settling permanently in London at the age of twenty-two. There he began writing to support himself, contributing pieces to local magazines and writing ‘London letters’ for the Bulletin. In this period he helped the Bulletin to snare the services of its preeminent cartoonist, the Englishman Phil May. In the autumn of 1888 – the year before Melba established her reputation in Roméo et Juliette at Covent Garden – Chambers achieved overnight fame with the staging of his play Captain Swift, produced by Herbert Beerbohm Tree, who also played the lead role. ‘Commissioned’ by Tree from Chambers in the street, and first read-through in the Turkish Baths in Leicester Square, the play about a bushranger after whom ‘the long arm of coincidence’ reaches was to be Chambers’s only overtly Australianthemed work apart from Thumb-nail sketches of Australian life (1891).

In a memoir of Chambers titled ‘A Play-Boy of Two Worlds’ in the Century magazine of December 1921, his friend John Williams recalled that even when Chambers wrote nothing, and it was hard to see where the money was coming from, he and his ‘gentleman’s gentleman’, Hogg, were ‘ever on the go … now to Nice, now to Mentone, or to New York and Palm Beach’. The pair was ‘inseparable, though always maintaining the position of master and servant, and, if anything, Hogg was even more imperturbable and impenetrable than his master’, Williams wrote. Together, they redecorated a tiny garage in Park Lane, where their friends found them ‘splendidly set up’ with a sitting room that was the acme of contemporary taste and a billiard room that provided the backdrop for amongst the theatrical stars of the day. It seems that Chambers’s reputation as a man of the world was only enhanced by his Australian origins. ‘His speech and accent and choice of words were in the best British Empire style, which is always colonial... never of London and rarely of England, where, as a whole, the spoken language is clipped, slangy, pitched in impossible keys, with never the fine word reverence and vocal timbre of an educated colonial’, in Williams’s estimation.

Captain Swift transferred to New York’s Madison Square Theatre, with Maurice Barrymore in the title role. Such was its success that Chambers’s next play, The Idler, premiered in that city. (Oscar Wilde was stung by critics’ claims that he had appropriated key devices of The Idler for Lady Windermere’s Fan, which premiered the following year.) For three decades Chambers worked on twenty or so plays, which were staged in the West End and New York, to which, he estimated, he made thirty visits. His outstanding successes included the melodrama The fatal card (1894), Passers-by (1911) and The saving grace (1917) as well as The tyranny of tears (1899), described by the New York Times as ‘one of the small number of perfect comedies of manners in the language’. Roger Neill, an authority on Australians abroad in the Edwardian period, wrote on Chambers in Quadrant magazine in 2008. He suggests that Australians have never bothered to claim Chambers because he is thought to have written ‘English high-society plays’, pointing out that the fact that Chambers ‘constantly satirised English attitudes from a fundamentally Australian stance’ seems, so far at least, to have been overlooked.

It suited Chambers to be married, for many years, to Mary Dewar, with whom he had a much-loved daughter, Margery. However, between 1896 and 1904 he was not only Nellie Melba’s acting coach, but her lover, spending many delightful hours with her taking tea in the garden of her home by the Thames, boating on the river, and at gatherings of their friends at the Savoy.

Melba was not attracted to cissies. Jim Davidson notes enigmatically that her husband, Charles Armstrong, father of her son, ‘agreeably combined exceptional skills as a rough-rider with the recommendation of gentle birth’. Similarly, Chambers’s experience on horseback, no less than his drawingroom ease, may have stood him in good stead with the lady. Bertram Mackennal, as well as Hugh Ramsay, was amongst their circle. Otherwise, however, Chambers’s connections with Australia were minimal; further diminishing his chance of commemoration here, he meant to visit, but never did. He and Melba broke up in 1908. The year before his death he married an actress with the professional name of Pepita Bobadilla. Incidentally, after Chambers died on 28 March 1921 – by some accounts, at the Bath Club – she married Sidney Reilly, ‘Ace of Spies’.

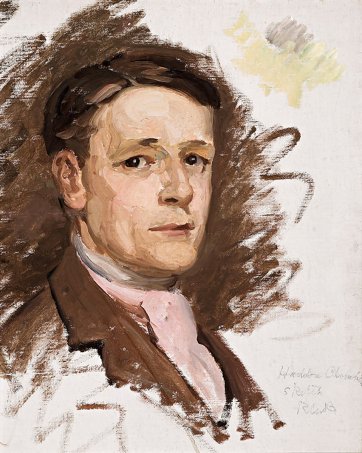

The portrait of Chambers was spotted by William Greenbaum, a print dealer from Massachusetts, who was about to list it on eBay when it occurred to him that it might be of interest to the Australian National Portrait Gallery.

He also wrote to London’s Victoria and Albert Museum offering the portrait; by the time they expressed definite interest, the National Portrait Gallery had committed to its purchase. To Greenbaum, the work was at least as interesting – if not more so – for its artist, as for its subject.

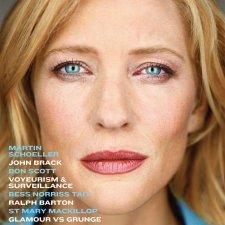

Ralph Barton, American cartoonist and caricaturist, produced a body of work that epitomises American high life in the 1920s. Barton was involved with the New Yorker from its inception, making eighty-five drawings in one week alone at the end of 1924. Noted particularly for his group drawings – such as, to take but one example, that of 128 Hollywood figures at the Cocoanut Grove – he worked for Vanity Fair, Harper’s Bazaar, the New York Herald Tribune and Life magazine amongst others, earning more than any other illustrator of his day. He illustrated Anita Loos’s Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and its successor, But Gentlemen Marry Brunettes. A representative handful of his portrait subjects comprises Charlie Chaplin, Ernest Hemingway, Sigmund Freud, Picasso, Lillian Gish and George Gershwin. Cursed with manic depression, married and divorced four times, Barton shot himself in his Manhattan penthouse at the age of thirty-nine. Soon, he was virtually forgotten.

This portrait of Chambers, reproduced alongside his friend Williams’s tribute, is a rare surviving ink-and-watercolour original artwork by Barton. In a New Yorker article about Barton and his ‘decoratively descriptive work, John Updike wrote that in the ‘fury’ of his life and career the artist was careless with his originals, most of which were destroyed, either by him or by his engravers. As a result, sadly, for the most part ‘indifferent, coarsely screened reproductions’ are all that remain of his output. The best of Barton’s art, Updike wrote, ‘is like a perfect flower, wiry and fluent, blooming in the wilderness of his era’s commercial art.’ It is an excellent description of Barton’s representation of Chambers – of whom Williams, recalling dawn departures from the jewelbox home in Aldford Street, wrote ruefully that ‘I like to think of him as still standing, waving me farewell as my cab turned the corner, flinging after me some parting bit of his cynical philosophy.’