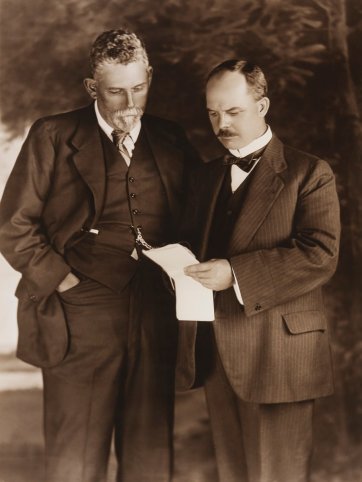

In its latest round of acquisitions, the National Portrait Gallery purchased a vigorous representation of Sir Sidney Kidman. The charcoal drawing is the second portrait of Kidman to come into the collection; the Gallery acquired a Falk Studios photograph of him with his fellow pastoralist, Arthur Bryant Triggs, in 2007.

Sir Sidney Kidman (1857-1935) is inscribed in Australian legend as the ‘Cattle King’. Born in South Australia to parents who had emigrated from England, Kidman seems to have had a dreary childhood. When he was a baby, his father died, and was buried in an unmarked grave because his widow was unable to afford a headstone. Soon, Kidman’s mother prevailed upon her neighbours, the Starrs, to send one of their sons to help around her property. Notwithstanding that he was a teenager, and she was not only thirty-eight but the mother of six sons under ten, she was soon pregnant, and she married him. According to Kidman’s biographer Jill Bowen, Starr was a ‘drinker and a brawler’ but the couple had more children together while he continued to work for her as a paid employee. Sidney escaped this situation at thirteen, initially gaining work with an itinerant cattleman. He was to live out of a swag for the next fifteen years, before he married and bought a house in Adelaide. Although she was eventually to make him a handsome bequest, Kidman is thought never to have seen his mother again, and his father’s grave remained untended.

Having served as a rouseabout and stockman around Broken Hill for some years, Kidman bought a bullock team and began carting supplies between isolated settlements in New South Wales and Victoria. In the early 1870s he established a butcher’s shop in Cobar that was successful enough for him to set up as a squatter. Henceforth he bought and sold cattle and horses to add to the income he was earning from his coaching enterprise Kidman and Nicholas, which was the main competitor with Cobb and Co. in New South Wales and Western Australia.

In the 1880s Kidman bought his first station, in the Northern Territory; by 1903 he had twenty-one holdings. Over the following years he built up two giant constellations of properties stretching across Queensland, New South Wales, South Australia and the Northern Territory, his stations sprinkled thickly from Cairns down to Port Augusta. Eventually, he held land almost equal in area to that of Victoria – or about 3.5% of the total landmass of Australia. Accordingly, he was able to move cattle about depending on where the rain had fallen, or the water was flowing. Kidman’s properties were to cut a raw swathe through Aboriginal lands in Central Australia, and his business was to impact dramatically on traditional ways of life. Personally, however, he appears to have maintained good relations with his (mostly unpaid) Indigenous employees, and a degree of respect for Indigenous tradition. Socialist agitator Michael Sawtell, a prominent member of the now-contentious Aborigines’ Welfare Board, reported in the journal Dawn in the 1950s that in his will, ‘the Cattle King ordered that all [A]borigines on his stations should be allowed to end their days there in peace and plenty.’

A gregarious, handsome and uxorious man, Kidman was also a teetotaller and was notorious for stinginess. Jill Bowen, however, believes that tales of his thriftiness – such as his sacking men for striking matches when there was another fire source nearby – are exaggerated, and on Russel Ward’s account in the Australian Dictionary of Biography it was only his horror of waste that made him appear hard. He contributed substantially to the armed forces and charities during the war, and was knighted in 1921, the day after he donated his home, Eringa, to the South Australian government.

Samuel Johnson Woolf, an American artist who drew hundreds of cover portraits for Time magazine, made this drawing of Kidman to accompany an article that appeared in the New York Herald Tribune on 3 July 1932.

Few people outside the wool trade recognise the name of Arthur Bryant ‘AB’ Triggs (1868–1936), yet for convenience, and to provide a kind of scale, Triggs is sometimes dubbed the ‘Kidman of the wool industry’, or the ‘Sheep King’. Although Triggs’s prospective biographer, Alan Ives, believes them to have been friends, Kidman and Triggs were very different. Kidman was never comfortable with the written word, was most relaxed in the bush, and seems to have had no hobbies outside his multifarious business deals and concerns. Triggs was a complete contrast.

AB Triggs was born and educated in England before coming to Sydney at the age of nineteen. Having joined the Bank of New South Wales, he found himself at the Yass branch as an accountant in late 1888. Settling in the town, in 1896 he bought his first eight thousand wethers. The next year, having sold them at a profit, he resigned from the bank. From that time on, Triggs bought and leased properties from Bourke to Kiandra, establishing a pattern of running between 250 000 and 500 000 sheep as well as some cattle at any one time. Triggs masterminded his operations from Yass until 1915, and it became a truism that when Triggs prospered, so did Yass. In 1915 Triggs moved his office to Sydney. That year, through the combination of drought and war, he went bankrupt, but by 1921 he had paid off all his creditors with interest, cementing his reputation for professional integrity.

Triggs travelled frequently to London, and there he indulged his serious passions for prints and drawings, old books and manuscripts and coins. Walter Spencer, a London book dealer who catered to wealthy international customers such as the pickle magnate Henry Heinz, stated in his memoir Forty Years in My Bookshop that he had known ‘no more enthusiastic collector than Mr Triggs.’ According to Spencer, Triggs’s great ambition was to establish a museum at Yass of his material relating to Charles Dickens. Although his dream of a museum of Dickensiana came to naught, Triggs was a generous contributor to the development of Yass’s more conventional public institutions. After he died at his home, Linton, in Yass in 1936 a distinctive gateway, funded by public subscription, was erected in his honour at the entrance to Victoria Park. In 1945, the contents of Linton were auctioned the catalogue of which indicates the dazzling scope of Triggs’s collections. He had drawings by Watteau, Dürer, Rubens, Vandyk, Rembrandt, da Vinci, Michelangelo, Tiepolo, Velasquez, Gainsborough, Reynolds, Constable and Whistler. He had letters and documents signed by Henry viii, Edward vi, Mary i, Elizabeth I and later English monarchs; by Marie Antoinette, Napoleon and various French kings. He had items signed by Cromwell, Charles Darwin and James Cook as well as Charles Dickens; he had Nelson’s penultimate signature, on a note to Henry Blackwood written on the night before the Battle of Trafalgar.

The Gallery’s double portrait of Sidney Kidman and Arthur Triggs was taken in a mainstream photographic studio, probably between 1911 and 1913. Though a photograph of two no-nonsense men, it is a teasing, mysterious artefact. Triggs is not mentioned in any accounts of Kidman, and Triggs’s descendants are unable to shed light on how, when or why the two men ended up posing together. The pastoralists are pictured in their city outfits, looking intently at a document that Triggs is holding, yet notwithstanding that there were at least two stations that each man owned at separate times Alan Ives has found no record of direct dealings between Kidman and Triggs. Which city’s Falk Studios it was taken in, whether the photograph commemorates some sort of agreement or contract between the men, whether the piece of paper on which they focus is a genuine document or simply a prop to hand, are all unknown. One senses, however, that Kidman, at least, is barely suppressing a laugh. Perhaps it had been a long luncheon at the Australian Club. Or perhaps he was delightedly anticipating the bafflement of future researchers, unable to see what he sees on the paper before his eyes.