Migration to a distant and unknown land is always a risky business, a move best suited to the young with nothing to lose. Benjamin Duterrau was sixty-five when he left a modest career as an artist and engraver in Britain for a new life in the colonies.

True, he had the offer of a job when he, together with Sarah Jane, his only daughter, boarded the Laing and arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in August 1832. By the time Duterrau arrived in Hobart the job of drawing master and music teacher at the school in Ross had been taken by Henry Mundy. Duterrau was clearly a man determined to make his mark: he was the first man in the colony to give an art history lecture (on the civilizing influence of art and the relationship of art and science) at the Mechanics Hall in Hobart just months after his arrival. He made Australia’s first etching and he made Australia’s first ambitious history painting. He had the immigrant’s willingness to take risks and had reached an age where he wanted to make a difference.

Duterrau’s strong moral purpose found a cause he could follow in the work of builder and lay preacher George Augustus Robinson (1791–1866). Relations between the Indigenous Tasmanian peoples and the settlers had deteriorated to what was in effect an undeclared war. Lieutenant-Governor Sir George Arthur had tried to corral the Aboriginals with a cordon of settlers – the Black Line – in 1830 with little success but eventually conflict and disease reduced the native population to perhaps as few as 300 people. Arthur then turned to diplomatic overtures as a way to end the dispute commissioning Robinson, who had been appointed protector of the Indigenous Tasmanian peoples on Bruny Island in 1828, to take his mission to the mainland and build bridges between the native Tasmanians and the new arrivals. Robinson took a number of the Bruny Islanders with him on his expeditions along the coast and into the interior as guides and interpreters, including Trukanini and Woorrady. By 1835 Robinson had managed to persuade the remaining people to move to a new settlement on Flinders Island, called Wybalenna, where he promised a modern and comfortable environment, and that they would be relocated to the Tasmanian mainland as soon as possible. There was the notion of history being made and Duterrau saw both duty as an artist and opportunity for sales in recording it. He began a series of drawings, etchings and paintings of the Indigenous Tasmanians that were to culminate in The Conciliation 1836, the first major history painting made in Australia.

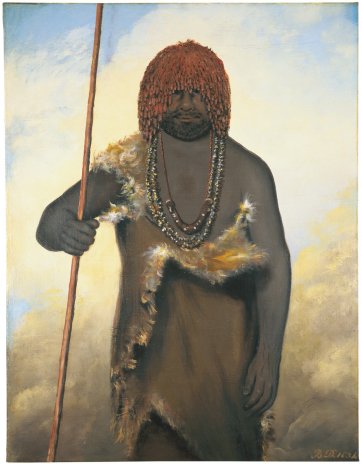

The Hobart Town Courier of 20 December 1833 noted that ‘We had the pleasure the other day of visiting Mr Duterrau’s collection of paintings in Campbell St to be agreeably surprised by remarkably striking portraits of our old sable acquaintances the [A]borigines of this island. They are all drawn exactly in the native garb. Wooreaddy the native of Brune Island, who has attended Mr Robinson in all his expeditions, has his hair smeared in the usual way with grease and ochre, three rows of shining univalve shells strung around his neck, the jaw bone of his deceased friend suspended on his breast. This relic of affection is carefully wrapped round with the small string which these interesting people make from the fibres of the large flax or juncus which grows on all parts of the island. A kangaroo skin with the fur inside is passed around him and fastened over the shoulder in the usual manner in the bush, before they obtained blankets from the whites and his brawny athletic arm is stretched out to wield the spear, His wife Trugganina, the very picture of good humour, stands beside him with her head shaved according to custom by her husband with a sharp edged flint. Great praise is due to Mr Duterrau for his fixing on canvas which may commemorate and hand down to posterity their original appearance and costume of a race now all but extinct.’

Aware of the unfolding tragedy, Duterrau determined that he should make a series of initial studies that would be worked into a bigger composition. While some have remarked on the simplicity of the prints, he was a highly skilled printmaker. In Britain Duterrau had shown not only paintings but prints, including renderings of other artists’ works. His portraits of Trukanini and Woorrady were produced as etchings to be sold to raise money for the production of what was soon to be called ‘the National Picture’. While the article describes the paintings, it effectively notes the salient features of the etchings, which derived from the same original sittings. Duterrau assures the viewer, with justifiable pride, that each plate was ‘Design’d, etch’d and publish’d by B. Duterrau, Aug. 24 1835 – Hobart Town Van Diemen’s Land’.

Duterrau was aware of the importance of his subjects and treated them sympathetically. He was conscious too of history and in an album of drawings and etchings he noted that: ‘Truggernana / A native of the southern part of V.D. land & Wife to Woureddy / was attach’d to the mission in 1829 / Truggernana has render’d very essential service to the / expedition on many occasions & in a most remarkable manner / Saved Mr. Robinson’s life by swimming & propelling / at the same time a small spear of wood to which Mr. / Robinson was clinging while endeavouring to cross / the river Arthur to get away from some natives / who had form’d a plan to kill him. but not being / able to swim he owes his life to Truggernana.’ A similar hand-written note accompanies image of Woorrady: ‘Woureddy / A wild native of Brune Island one of Wm. Robinson’s most faithful / attendants attach’d to the mission in 1829 / Bm. Duterrau. / Wourreddy was present at all Mr. Robinson’s interviews with the blacks / through the intervention of this man Mr. R. has been preserved from ex/ treem [i.e. extreme] dangers when his life was about to be taken from him - / There is much history connected with this individual, a full account / will appear in Mr R’s publication.’

Duterrau died on 11 July 1851, aged eighty-four. The CornwallChronicle of 19 July described him as a ‘highly talented artist and much respected’. His best works were sent to his daughter in Britain and the remainder of his estate was sold at auction by a Mr Elliston on 27 August 1851 at Mr Robin Hood’s picture gallery, Liverpool Street. The engraved copper plates were sold to John Watt Beattie, photographer and collector. There appears to be two groups of etchings. The first etchings were likely printed by the artist himself in small editions. This was not from sense of propriety or respect for the cult of the limited edition but because his production was based on demand and demand was low. A second group of prints was made later, most likely by JW Beattie using the original plates. And where the early edition used laid paper, the later edition was printed on a modern wove paper. Prints in the later edition have the original price of 1/6 rubbed out so that they could be sold at a new price.

Duterrau’s painting The Conciliation was created with an optimistic view of history in the making. He could not be aware of the full price that had to be paid by the Tasmanians he pictured.

![Woureddy [Wurati], a wild native of Brune Island Woureddy [Wurati], a wild native of Brune Island](/files/8/9/0/b/i8536-th.jpg)

![Truggernana [Trukanini], a native of southern part of V.D. Land Truggernana [Trukanini], a native of southern part of V.D. Land](/files/1/8/5/e/i8535-th.jpg)