Frank Hurley was ‘a great chap to be away with’ according to an observation made in the journal kept by aviator Eric Douglas during a voyage to Antarctica in the summer of 1929 and 1930.

Written during Sir Douglas Mawson’s cumbersomely-named British, Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE for short), Douglas’s journal presents a vivid vignette of daily life during a venture of substantial scientific and political consequence, a candid and personable record that mirrors the images taken by Hurley, the expedition’s official photographer. Known for their memorable depictions of heroic exploits in the frozen south, Hurley’s images are also plentiful in what they yield about the daily life of ordinary men in extraordinary circumstances.

BANZARE’s leader Sir Douglas Mawson (1882-1958) first ventured to Antarctica with Sir Ernest Shackleton’s British Antarctic Expedition (1907- 09) and later led the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) of 1911 to 1914. Monumental for its achievements in science and exploration, the AAE is equally legendary for Mawson’s epic journey to the South Pole during which his two companions, Xavier Mertz and B.E. Ninnis, perished. Ninnis vanished into a crevasse with a sled-load of equipment and provisions and twenty five days later, Mertz succumbed to the combined affects of exposure, starvation, and poisoning from the livers of the sled dogs that had been supplementing supplies. Dangerously debilitated himself, Mawson made it 160 kilometres back to the base at Commonwealth Bay, only to see the expedition’s ship Aurorasteaming away without him. Mawson waited out another winter with the small party that had stayed to search for him, returning to Australia and adulation in 1914.

The third of Mawson’s expeditions to the Antarctic and the second under his command, BANZARE consisted of two ocean voyages – referred to, fetchingly, as ‘cruises’ – conducted over the southern summers of 1929-30 and 1930-31. Throughout the 1920s, Mawson had been lobbying the Australian government to assert its claim to a chunk of the Antarctic continent, using the achievements of the AAE as justification. In 1927, the government green-lighted an expedition which was primarily political and economic in intention – a means of planting flags at points along a swathe of Antarctic coast while investigating the commercial potential for whaling and sealing, but an expedition dignified by a comprehensive geographic and scientific program. The Australian and New Zealand governments contributed cash to the expedition but it was, nonetheless, largely privately-funded, a substantial share of the money coming from the Australian confectionary magnate, Macpherson Robertson. The British pitched in with the contribution of the venerable, ice-strengthened vessel Discovery, the veteran of Robert Falcon Scott’s Antarctic expedition of 1901-04 and in Eric Douglas’s words ‘capable of withstanding enormous crushing pressure’ with its oak sides around two feet six inches thick. Discovery carried thirty-nine men, a third of this number made up by the scientific staff hand-picked by Mawson for the task of ‘observations in the several departments of science embraced in our plans’. These plans included an aircraft, necessitating the appointment of two pilots – Douglas and Flight Lieutenant Stuart Campbell. The two aviators and what Douglas referred to as ‘our machine’ – a Gypsy Moth sea plane – were called into regular service, flying ahead of Discovery to identify routes through the pack ice and making ‘flights for photographs – both cine and still’ with expedition photographer Frank Hurley and his thirty-pound cinema camera. In a paper published in 1932, Mawson acknowledged that ‘the aeroplane proved a most important factor in the prosecution of the geographical programme. Its successful operation, at times under most difficult conditions, [owed] everything to the determination and skill of Campbell and Douglas’.

Observations in several departments of science also necessitated the employment of someone to record them and Mawson again called on the services of Hurley (1885-1962) who had served as official photographer to the AAE. In 1911, Mawson had been wary of appointing Hurley (British photographer, Herbert Ponting, had been his first choice). But in 1929 – and despite their fractious relationship – he knew the value of the ice-seasoned Hurley, a so-called ‘warrior with his camera’, renowned for his daring and incessant pursuit of the perfect image. In the 15 years between the AAE and BANZARE, Hurley had travelled to the Antarctic with Ernest Shackleton and created the celebrated photographs of the ship Endurance being slowly crushed and mangled in a grip of polar ice. He had made documentary films of travels in New Guinea and the Torres Strait, accompanied the adventurer Francis Birtles in his east-to-west crossing of Australia in a single cylinder car, and served as an Official War Photographer in Belgium and France, where he was nicknamed ‘the mad photographer’ for working so close to front line fighting.

The contrast between Hurley and Mawson is well documented: Hurley the mercurial showman and upstart from inner-suburban Sydney; and Mawson the donnish, polished, and measured man of science. Their contrasting personalities are hinted at in portraits of both men held in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection. Mawson’s portrait, photographed in a London studio during World War I, confirms descriptions of a striking, highly rational man of gentlemanly bearing. Mawson was also a man of immense stamina, characterised by his mentor, TW Edgeworth David, as being ‘of infinite resource, splendid physique and astonishing indifference to frost’. Seemingly at ease in the close confines of Antarctic expedition quarters, Mawson was similarly so in the fine hotels and clubs where, like other explorers, he conducted the business of raising money for his expeditions. Frank Hurley’s self portrait, taken around the time of his appointment to the AAE in 1911, is a charming image of a bright-eyed, somewhat impish young photographer on the eve of the assignment that would secure his reputation as a creator of Antarctic images often matchless in their verve and audacity. Hurley presented a potent mix of technical skill and daring, embellished with a finely-tuned eye for the sort of images that would seize the public imagination – a quality that Mawson knew would elevate the expedition’s images above the merely dry and documentary needs of science. Hurley’s photographs were vital as a means of recording scientific and exploratory activities, but – as moving pictures, as lantern slides, or as illustrations to popular published accounts – they were equally ripe for commercial exploitation and thus a crucial means of paying an expedition’s debts. Described by war historian Charles Bean as a ‘rare mixture of the genuine, highly sensitive artist and keen commercial man’, Hurley is known to have manipulated photographs to intensify their dramatic affect. Similarly, he filled gaps in the narratives of his BANZARE films, Southward Ho! With Mawson (1930) and Siege of the South (1931), with footage taken during the AAE.

Mawson would later let slip his distaste for the methods Hurley sometimes employed to animate his images – such as when he placed a gramophone amidst a group of penguins during a landing at Commonwealth Bay in January 1931 – seeing some of Hurley’s work as an example of the reduction of the expedition record to ‘a second grade popular story’.

Hurley’s dexterity for showmanship nonetheless resulted in exhilarating film footage and photographs which became the means by which a nation visualised its achievements in an unknowable continent. In the boy’sown- annual language of his diary, Hurley described himself ‘analysing every curve and play of light and shade, composing and exposing on a profusion of subjects’. He went to great lengths to get the best shots, his commitment to his craft evidenced by a seeming indifference to the harsh and perilous conditions he worked in. The existing difficulties of photography were multiplied immeasurably in the brutal climate of Antarctic latitudes – extremes of daylight and darkness, winter temperatures of minus twenty-one degrees, and storms and winds so fierce and persistent that Mawson would memorably describe Antarctica as ‘the home of the blizzard’. Hurley’s photographs are those which have the ability to astonish with their precise but charged depictions of men in a forbidding landscape.

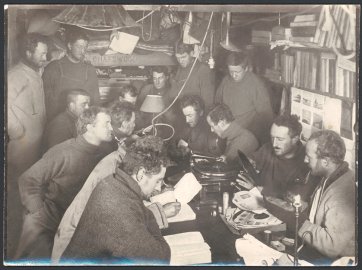

But they are also matter-of-fact documents of daily life and moving records of the human dimension of public ventures, disclosing the mundanities of work, routines and relationships. This is the realm occupied by Hurley’s portrait of Eric Douglas, photographed on the deck of Discovery in the signature Antarctic kit of head-to-toe wool and holding a pipe – an object which figures as something of a motif in Hurley’s portraits of expedition life. His images of down-time in Discovery’s wardroom or the AAE’s ‘winter quarters’ seem to reek with a mix of tobacco, coal dust, and wet wool, bearing out the scenes described by diarists like Douglas whose account makes references to the employment of books, whiskey, games, and a gramophone below deck. At other times he records receiving his ration of 300 cigarettes and catalogues the expedition-issue shirts, stockings, mitts, pullovers, and hats – ‘all these articles are made of wool and are of special thickness and make’ – and is frank about the few opportunities afforded for shaves and baths. But ‘you don’t worry what you look like or how you dress’, he wrote, ‘and I think a spell like this does us all good’. Hurley’s informal and affectionate portrait of Douglas also suggests something of the camaraderie between subject and photographer. Douglas’s journal hints that, in Hurley, he had found a like mind amidst the boatful of science boffins and Hurley’s high spirit and facility for jokes is said to have made him popular with other expedition members. Hurley’s weathered but slightly smirking face, front-and-centre of his iconic group portrait of the scientific staff of the second BANZARE cruise, is a distinct presence in an image that evokes the stoicism, pride and comradeship of men engaged in an internationally significant event.

Following BANZARE, Mawson returned to academic life at Adelaide University and would come to be numbered among the twentieth century’s greatest explorers. His friendship with Hurley eventually ended amidst disagreements over the filmic and photographic records of the two Antarctic expeditions they had made together. In the 1930s, Hurley continued to make films, served as a photographer again in World War II and spent the later years of his career travelling, photographing and publishing books of his work. Awarded the Polar Medal for his participation in the BANZARE voyages, Eric Douglas returned to RAAF service but made a further trip to the Antarctic on a search mission for the American explorer, Lincoln Ellsworth, in 1935. The acquisition of Douglas’s portrait by his erstwhile expedition cohort augments the National Portrait Gallery’s holdings of Antarctic figures, a modest but important document of a major moment in Australian science and a vivid reminder of the nation’s stature in the twentieth-century’s ‘Heroic Age’ of polar exploration.