Nancy Bird Walton AO OBE (1915-2009) had a taste for flight from the start. In autobiography and in interviews throughout her long life, Bird Walton recalled launching herself, arms outstretched, from a backyard fence at the age of four.

As a six-year-old she witnessed an aeroplane landing on Dee Why Beach: ‘It was an old First World War aeroplane and it seemed to have a magnetic attraction for me’. In her early teens, she left school and returned to country New South Wales to help her father run his general store. Aged thirteen, she went to an air pageant and parted with a week’s wages for a joyflight, convincing the pilot to ‘do some aerobatics with me’, after which flying became the ‘ruling passion’ of her life. In 1933, she left again for Sydney with the £200 she had saved for flying lessons and fronted up – aged seventeen – to Charles Kingsford Smith’s flying school at Mascot, graduating with a pilot’s licence a mere six weeks later.

Her determination to fly met with some resistance from a father with a more conventional fate in mind for his daughter, but in Sydney Bird Walton encountered an aviation scene with an anything-goes attitude at a time when women flew for thrills and leisure. Inspired by European fly-girls like Amy Johnson and Ellie Beinhorn, she acquired her own aeroplane and went barnstorming with another female pilot, Peggy McKillop. The two women flew from town to town, following the path of shows and race meetings, making money from joyflights and causing a stir in the process. She earned her commercial pilot’s licence in 1935, and in the same year became the first Australian woman to work commercially in aviation when she was appointed pilot for the Far West Children’s Health Scheme. Fellow aviators like John Flynn and PG Taylor doubted that a woman had the skill or wherewithal to ‘stick it’ in such a role, yet Bird Walton flew this aerial ambulance service for the next four years and then operated a charter business in Queensland without giving a thought to the perils of her work – ‘you learnt to fly an aeroplane and you went out and did a job’. Photographs of Bird Walton at this time confirm her youthful independence while also speaking of the slick and foxy leather-clad glamour of aviation in the 1930s. In 1938, she went to Europe and spent a year studying airlines and the aviation industry, returning to Australia and marrying in 1939. Ironically, the outbreak of war halted the deployment of skilled women pilots who were seen by some as a threat to the employment of men. Bird Walton nevertheless contributed to the war effort as a commandant in the Women’s Air Training Corps. For a time, she became interested in politics, befriending figures like Nugget Coombs and entertaining an idea of running for parliament. In 1950 she founded the Australian Women Pilot’s Association and later returned to air racing. In 1958, she was the first woman from outside the USA to enter the All Women’s Transcontinental Air Race (aka the ‘Powder Puff Derby’) and entered it again in 1961.

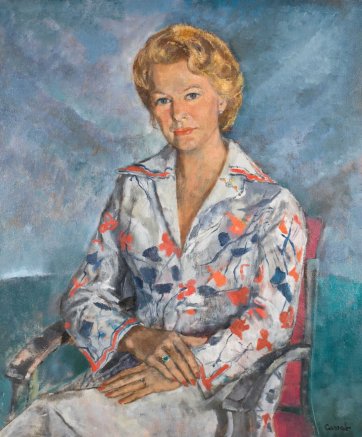

Despite this, Bird Walton was seemingly blasé about her achievements and by 1977 would describe herself as having been ‘small fry’ in the field of aviation. While indeed proud of what she and other women had achieved in an otherwise masculine realm, in her later years Bird Walton would come to see her main claim to recognition as residing in her charity work and other contributions to public life. This poised, unassuming guise is mirrored in her portrait by Judy Cassab created, curiously, as an afterthought to Cassab’s commission to paint Bird Walton’s husband, Charles, in 1973. Gifted to the National Portrait Gallery in 2008, Judy Cassab’s luminous, elegant portrait presents an endearing image of an extraordinary woman, but one which can only hint at the grit and adventure of the former life that makes its subject so exceptional.