To see the portraits of James Cook and Joseph Banks side by side in the Robert Oatley Gallery of the National Portrait Gallery is to come thrillingly close to time travelling. The two men spent three years together – from August 1768 to July 1771 — in the cramped confines of the bark Endeavour.

Lieutenant James Cook took command of the Endeavour in his fortieth year. While his formal schooling had ended when he was about twelve, assiduous studies in his twenties enabled him to write an account of an eclipse that was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1766. The level of detail in this article attested to his fitness to report on the transit of Venus across the sun, the publicized reason for the Endeavour expedition of 1768. Furthermore, during the Seven Years’ War, Cook had served with distinction under Sir Hugh Palliser — who was to become Comptroller of the Navy; and in the first half of the 1760s he had demonstrated and refined his capacity for accurate surveying and mapping in the waters around the St Lawrence River and Newfoundland. One of his superiors wrote to the Admiralty that Cook’s work evidenced ‘pains and attention … beyond description’. In these years, then, he had proved himself eminently suited to carrying out the major covert purpose of the Endeavour voyage, which was the search for a southern continent, long supposed to exist somewhere between Africa, South America and the Antarctic. Though not the Society’s first choice, Cook was, crucially, the Admiralty’s.

There is scant written record of how the young landed gentleman, Joseph Banks, secured his berth on the Endeavour. A letter from the naturalist Daniel Solander to his mentor, Carl Linnaeus, records that he and Banks together applied to the King to obtain passage on the ship, and their request ‘was so well received … that the captain was ordered to give us the best cabins and to receive as well 3 draughtsmen and 6 hands who all belong to Herr Banks’. They boarded the Endeavour in Plymouth Sound on 26 August 1768, and the vessel set sail that day. Banks’s party — paid out of his own capacious pocket — included Solander, the artists Sidney Parkinson and Alexander Buchan, the naturalist Herman Spöring, four servants who doubled as specimen collectors, and two dogs. The extent of his cargo, Banks admitted, almost frightened him — scores of books, apparatus for catching animals, preserving jars and bottles, salts, wax and other botanising paraphernalia.

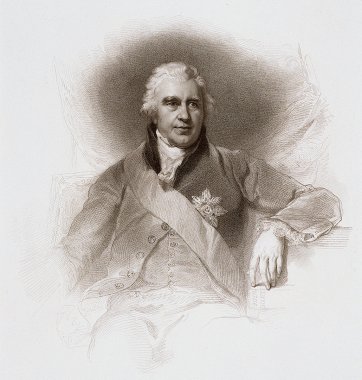

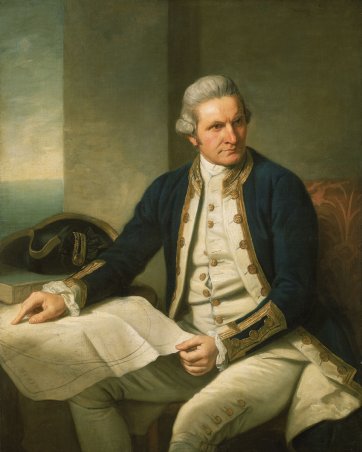

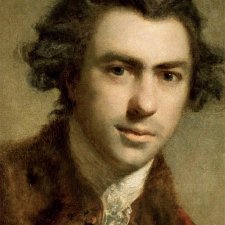

The portraits of Cook and Banks were painted about ten years apart. Reynolds shows Banks in his late twenties, whereas Webber’s posthumous portrait of Cook shows him aged about fifty, his age at the time of his death. There was a fifteen year age gap between the two men, and the difference in their backgrounds was profound.

Born in Marton, Yorkshire, Cook attended a village school in Great Ayton, and helped on the farm where his father was foreman. In his early teens he abandoned life on the land, working in a shop in Staithes before becoming apprenticed to Whitby shipowners. Joseph Banks was born to Lincolnshire landowners in 1743. By the time he proceeded from Eton to Oxford to pursue his interest in botany, Cook had transferred from merchant ships to serve in the Navy. Cook married in 1762, and his first son was born the following year. In 1764, having come into his inheritance, the bachelor Banks set up house in New Burlington Street. Two years later, he made the first of his dedicated botanising excursions, to Cook’s old stamping grounds, Newfoundland and Labrador. Although Banks had left Oxford without gaining his degree, he was elected to the Royal Society in 1766. The Society recommended him for the Endeavour expedition as ‘a Gentleman of large fortune … well versed in natural history’.

Throughout the years of the Endeavour voyage, Cook and Banks slept in cabins separated only by a small ‘lobby’. Banks’s, lacking an external wall, had no porthole. Notwithstanding that to accommodate Banks’s retinue the ship’s officers had been consigned to specially constructed accommodation on the lower decks, Banks and Cook, along with the astronomer Charles Green, Solander and all the rest of Banks’s party occupied a space less than seventeen metres long. In the Great Cabin, onto which Banks’s and Cook’s rooms both opened, the officers, botanists and illustrators dined, talked and wrote up their journals. In the early weeks of the voyage, Banks was a little frustrated by the ship’s speedy progress. While Cook forged on, the naturalist had little to do; a couple of months out from Plymouth, Banks was exercising, ‘playing tricks with two ropes in the Cabbin’ when he fell over and hit his head, sustaining a mild concussion.

The transit of Venus was to be observed at Tahiti, recently disclosed to Europeans by the Englishman Samuel Wallis. The Endeavour reached there many weeks before the scheduled astronomical event. In the intervening time, Banks wrote a long and multifarious account of the ‘Manners and customs of S. Sea Islands’, in which he dilated, for example, upon the ‘infinite smoothness’ of the Tahitian women’s skin. While the concoction of coconut oil, sweet wood and flowers with which the islanders anointed their bodies struck him as ‘most disagreable’ at first, he found that ‘very little use reconcild me at least very completely to it’: These people are free from all smells of mortality and surely rancid as their oil is it must be preferred to the odoriferous perfume of toes and armpits so frequent in Europe. Scholars have pored over Cook’s punctiliously detailed journal in an attempt to distil the nature of the man. His great biographer, JC Beaglehole, reported resignedly in 1969 that ‘searching around, as I do, for the man — some leading characteristic, some not very secret spring — I light on … stubbornness’. Though Cook’s journal was written — and extensively rewritten — to hand over to the Admiralty, Banks had a very different readership in mind. When one of his illustrators, Buchan, died in the first year of the voyage, Banks paid tribute to the ‘ingenious and good young man’. At the same time, he admitted that ‘his loss to me is irretrievable, my airy dreams of entertaining my friends in England with the scenes that I am to see here are vanished’.

The journals yield next to naught as to the relationship between the two men. Cook’s references to Banks are confined to the occasional note that he went ashore, or out in his little boat, botanising. In turn, Banks never elaborates on the character or actions of the captain, although the reader is tantalised with opportunities for personal revelations. Banks relates, for example, that in August 1770 he and Cook spent the night on Lizard Island, where they ‘slept under the shade of a Bush that grew on the Beach very comfortably’; but their drowsy exchanges can only be imagined.

In many passages the two journals are very similar. The accounts of New South Wales, for instance, conform closely, and disappointingly, given that in this section of Cook’s journal the former farmhand gives rein to an uncharacteristic expression of opinion, noting the ‘Tranquillity’ enjoyed by the Indigenous inhabitants, who appear undisturbed by what he calls ‘Inequality of Condition’. It seems reasonable to suggest that Cook was so preoccupied with the business of navigation and administration that, once seated across the table in the Great Cabin, he was happy enough to crib passages by Banks when their content was all he required. However, historians are ever attuned to class questions, and such a simple explanation will not always do. Some have implied that the villageschooled, unimaginative Cook had no option but to copy from the cultivated gentleman, and even that he regarded exposure to Banks as educative. Others, such as the autodidact Ray Parkin, hotly dispute that Cook was incapable of observing, or describing, complex phenomena on his own, and that it was that pampered amateur, Banks, who was lucky to be around Cook in his formative years. Parkin, who frankly conceives of Cook as Spinoza’s ‘whole man’, suggests that Banks, ‘without the burden of responsibility or the insight of profounder knowledge of the realities’, took Cook’s expertise for granted, attributing the ship’s successful progress up the coast of New South Wales to ‘our usual good fortune’ instead of to the captain’s unique abilities.

One night in the second week of June 1770 the Endeavour struck a coral reef. Having scrambled from complacent slumber onto the deck, Banks could soon see ‘her sheathing boards &c. floating thick round her’. Though conceding that he was ‘unusd to labour’ he took his turn with the crew to pump water from the flooding ship. The men’s unceasing effort he slated home to the demeanour of Cook’s officers, ‘perfectly composd and unmovd by the circumstances howsoever dreadfull they might appear’. For his own part, Banks confessed: I entirely gave up the ship and packing up what I thought I might save prepared myself for the worst … we well knew that our boats were not capable of carrying us all ashore, so that some, probably the most of us, must be drowned.

This, he conceded, might be better than reaching the barren land, to starve or — in the event that they met with ‘good usage’ from the local inhabitants — to live ‘debarred from … conversing with any but the most uncivilizd savages perhaps in the world’.

The Endeavour broke free of the coral, and the employment of innovative measures enabled Cook to bring the disabled ship in to the place now known as the Endeavour River. Here, the many weeks it took to repair the damage afforded Banks the opportunity to range widely for specimens. Though tormented by musquetos, he happily nabbed possums, and espied, studied, killed and ate that fascinating animal they learned, from the locals, to call the kangaroo; ‘nothing certainly that I have seen at all resembles him’, he wrote. The range of available plant and animal food was a comfort, for Cook was facing the real possibility of months’ wait for a favourable wind. On 18 July, Banks accompanied Cook to a high hill about eight miles up the river, where the view ‘afforded us a melancholy prospect of the difficultys we were to encounter, for in whatever direction we turned our eyes Shoals innumerable were to be seen’. On 20 July Banks wrote: ‘We were ready to sail with the first wind but where to go?’

They departed on 4 August, with Cook resolving to hug the land lest he should miss determining once and for all whether New Guinea was separate from New Holland. Within a fortnight, however, they had sailed into a treacherous impasse, which he vividly evoked: All the dangers we had escaped were little in comparison of being thrown upon this reef where the Ship must be dashed to pieces in a moment. A reef as is here spoke of is scarcely known in Europe, it is a wall of coral rock rising almost perpendicular out of the unfathomable ocean … the largest waves of the vast Ocean meeting with so sudden a resistance make a most terrible surf breaking mountain high.

After an agonizing eighteen hours, Cook capitalized on a faint, freak breeze to manoeuvre the ship into an exiguous channel: ‘dangerous as it was it seem’d to be the only means we had of saving her as well as ourselves’, he wrote. Steering the Endeavour through this narrow ‘mill race’ has been described as his greatest feat of seamanship.

Although Cook called his exit route the Providential Channel, both his and Banks’s descriptions of this nightmare appear to testify to a shared secularity. The scholar of the Enlightenment, Roy Porter, notes that Banks had ‘a deep sense of social responsibility but scarcely a trace of Christian piety’; and though Banks wrote ‘the fear of Death is bitter’, he failed to thank God for intervening on this occasion. Cook had appeared impassive throughout the terrible juncture, but in fact it gave rise to a very rare moment of disaffected introspection: Were it not for the pleasure which naturally results to a man from being the first discovrer, even was it nothing more than sands and shoals, this service would be insupportable especially in far distant parts, like this … The world will hardly admit of an excuse for a man leaving a Coast unexplored he has once discover’d, if dangers are his excuse he is then charged with Timorousness and want of Perseverance and at once pronounced the unfitest man in the world to be employ’d as a discoverer; if on the other hand he boldly incounters all the dangers and obstacles he meets and is unfortunate enough not to succeed he is than charged with Temerity and want of conduct.

As far as Beaglehole could see, Cook had ‘no religion and no politics’. The life-or-death drama played out on the reef seems only to have stimulated him to assess his own profession and career in broad terms, not to reflect on questions of mortality, faith or meaning.

At no stage of the journey do Cook’s and Banks’s journals diverge so widely as during their three months in Batavia (Jakarta) in Dutch-administered Java. There, Cook was entirely occupied with the repair and refitting of the Endeavour — so badly damaged that ‘it was a Matter of Surprise to every one who saw her bottom how we had kept her above water’. The refurbishment entailed a great deal of diplomacy and paperwork (including the negotiation of a government loan); the work had to be undertaken in a Dutch shipyard — with which Cook was unexpectedly impressed. While the captain went about transacting and documenting this demanding business, Banks set down his observations of Java — its natural specimens, languages, fortifications, economy and beliefs — peppering them with snide asides about the Dutch. While he regretted that illness precluded his writing a fuller account, his notes suggest that for a time, at least, he ignored his infirmity to prosecute his customary hedonism. It was local practice, he wrote, to scatter beds with flowers: so that you sleep in the midst of perfumes, a luxury scarce to be expressd, nor at all conceivd in Europe … [S]tewing under 3 or 4 blankets even fragrant odours cannot enjoy that liberty they do [under] the covering of a single peice of fine Chintz.

On 26 October Cook supposed that his men were suffering under the ‘extream hot weather’. By 9 November, however, they ‘were so weakend by sickness that we could not muster above 20 Men and officers that were able to do duty’. Seven men died in the port and they left it at the end of December with more than forty men ill. Sick himself, Cook concluded that on account of its unwholesome air, ‘Batavia is certainly a place that Europeans need not covet to go to’. A few weeks after leaving Java, the crew members succumbed to fever and flux in droves; by the end of January the Endeavour was scarcely manned; Cook described it as a ‘Hospital Ship’ and the men’s situation as ‘calamitous’. At this point, his journal becomes a catalogue of losses, interspersed with poignant records of his continuing efforts to maintain hygiene by swabbing the decks with vinegar. In all, thirty men were lost as a result of the stint in the port; Green, Spöring and Parkinson died within three days of each other in late January. It was not until the end of February that the last victims, including Solander, recovered.

The Latin inscription on Reynolds’s portrait of Banks translates as ‘tomorrow we’ll sail the vasty deep again’; but Banks did not sail with Cook again. At the beginning of 1772 he and Solander were well on the way to joining Cook’s next expedition, on the Resolution, along with an entourage including the painter Johann Zoffany, two horn players, and vastly more botanising equipment than the Endeavour had lugged. Cook noted with amusing restraint that ‘it was found difficult to find room for the whole and at the same time leave room for her officers and crew and stowage for the necessary stores and provisions’. Extensive modifications were made, but though Cook had ‘reson to think that she would prove Crank and that she was over built’, he ‘suspended giving any other opinion until a full trial had been made of her’. On 2 May 1772 Banks hosted a reception on board for the Earl of Sandwich and the French Ambassador. The Resolution set off down the Thames but soon proved ‘so crank that it was thought unsafe to proceed any further’. The Admiralty and the Navy Board were called in to adjudicate; Cook commented: I shall not mention the arguments made use of by Mr Banks and his friends as many of them were highly absurd … be this as it may the clamour was so great that it was thought it would be brought before the house of commons.

The rectifications to the modifications, which took some weeks, did not satisfy the men of science; Cook wrote: ‘Mr Banks declared his resolution not to go the Voyage, aledging that the Sloop was neither roomy nor convenient enough for his purpose.’

Banks appears to have held no grudge against Cook over the accommodation fiasco. In 1776, four years after the events described above, he moved to Soho Square. Incorporating a library and natural history museum (the vast collections of which were curated by Daniel Solander), his home there was to become a fashionable hub for educated society. That year, he commissioned the portrait of Cook by Nathaniel Dance that is now in the collection of the Maritime Museum, Greenwich; until Banks’s death, it hung above the library fireplace in Soho. In November 1778, about the time that Cook arrived in Hawaii on his third voyage to the Pacific, Banks began his forty-two years as President of the Royal Society. Unhappily, within the next few years, it was to fall to him to supervise the production of the Society’s formal memorial to the navigator: the Royal Society Medal, issued to coincide with the publication of the narrative of the third voyage. Cook was killed in Hawaii in February 1779. Just two months later, Banks recommended Botany Bay to a House of Commons committee as a suitable site for a convict settlement.