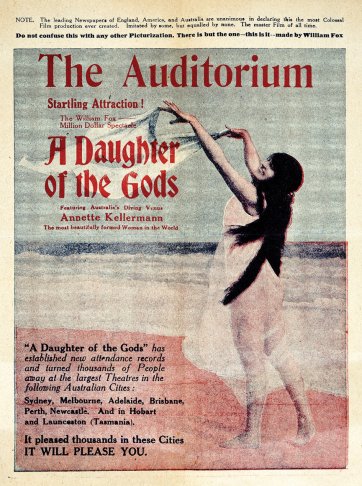

Australian cinema-goers in 1917 were promised ‘the most gorgeous spectacle of the age’ should they part with the couple of shillings required to see a film called A Daughter of the Gods.

Made in 1916, it was the first film to have a production budget of one million dollars, supposedly employing a cast of 20,000 extras as ‘gnomes, fairies, battling warriors and beauties’ in ‘entrancing scenes of Oriental splendour’. In Australia, it was advertised as being so popular that new attendance records had been set – and thousands of would-be viewers turned away – wherever it was screened in major cities. Cinema owners took care to tout the film’s dramatic credentials, for by concentrating on its artistry and lavishness they deftly avoided any direct reference to the main reason why it created such a sensation: the titillating peek it provided at the naked body of its Australian star, Annette Kellerman.

Arguably among the world’s most famous women at the height of her career, by the time she made A Daughter of the Gods Annette Kellerman was a performer of extraordinary diversity and accomplishment, the ‘Diving Venus’ whose vivid repertoire included acting, underwater routines, ballet, wire-walking, acrobatics, singing and impersonations. Described as the ‘queen of modern vaudeville’ in 1910, Kellerman was perhaps more renowned for possessing what a Harvard professor declared to be the ‘perfect’ female body, an asset readily exploited by the theatre entrepreneurs and box-office savvy filmmakers who helped establish her reputation. Not a tall, thin woman with the type of body idealised a century after she first achieved fame, Kellerman was a petite, 60 kilogram bundle of supple muscle, honed and disciplined with swimming, the sport that was the launch pad for her success. Confident and assertive, Kellerman can be considered an embodiment of ideas about Australian identity that reached their apotheosis in the archetype of the lithe, vigorous, beach-bred woman of the interwar years.

In her 1918 manifesto-toned Physical beauty: how to keep it, Kellerman credited swimming as ‘that magnificent sport to which, more than any other thing, I owe my personal development and success in life’. Born in Sydney in 1886, Kellerman suffered from rickets as a child and learned to swim when it was suggested as a way of overcoming the condition, ‘a healthful and necessary means whereby [her] limbs could be … free from the horrible steel braces’ she wore until the age of six. By the age of 13, she was setting records for women’s swimming in New South Wales and by 19 held every record for distances from 100 yards, including the world record for the mile. In an era when professional swimming was something of a blend of athleticism and cabaret, Kellerman set out to make her name both with feats of endurance and the ‘water ballet’ and diving demonstrations that would later win her gigs in London and New York. In Melbourne from 1903, Kellerman gave her first performances with exhibitions of swimming and diving at places like the Princes Court amusement park and the Exhibition Aquarium in Carlton where she performed routines in a glass tank. She garnered newspaper attention with distance swims down the Yarra in 1904, and in 1905, with her family’s fortunes foundering, Kellerman went to England, leaving the small and culturally remote pond that was turn-ofthe- century Australia to exercise her ambitions overseas, with it exporting her particular brand of Australian womanhood. In her part-autobiographical, partinstructional How to Swim (1918), Kellerman was unabashed in her admission of having outgrown the country where exceptional swimmers were all too garden variety. Australia ‘though big in area, was not big enough … to satisfy our ambition. In England were more people, more theatres, and more money to be earned’.

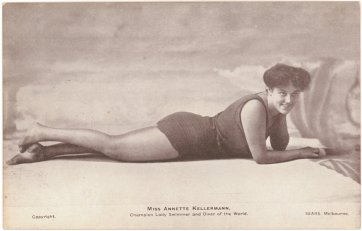

With her father’s support, she landed, bombshell-like, in drab London in mid 1905 and soon drew attention to herself by swimming 40 kilometres down the Thames. This attracted the interest of a journalist from London’s Daily Mirror, who agreed to give her further publicity should she undertake to swim the English Channel. She was the first woman to try this feat, training for the first of her three attempts by swimming along the English coast, back and forth between Dover and Ramsgate. Greased with porpoise fat, goggles glued to her face, Kellerman made it three quarters of the way to Calais before being forced back by the tide, later lamenting that she’d had ‘the endurance but not the brute strength’ to finish. She followed up the Channel swim with a marathon race down the Danube and another through Paris along the Seine. The only woman competitor and one of only four to finish, Kellerman’s account of the race boasted of the French ‘going wild’ for her, with thousands of people lining the river banks and crying ‘Allez, Mees!’. Accordingly, extant studio portraits of Kellerman from the early part of her career focus on the sensational and solid form that endured long swims of turbid waterways, exhibiting characteristics typical of other portraits of swimmers of the era in their forthright attention to Kellerman as a muscular physical specimen. Not pale, frail, weedy or prudish, Kellerman represented youth and fitness, the sort of specimen cultivated in sun and sea air. While her body would soon become famous, even scandalous, for a different type of aesthetic, its novelty initially lay in Kellerman’s amazonian capacity for endurance and her emergence on the international scene as a woman accomplishing physical feats thought the domain of men.

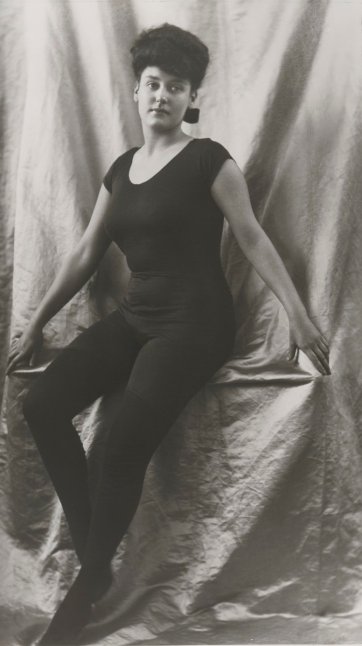

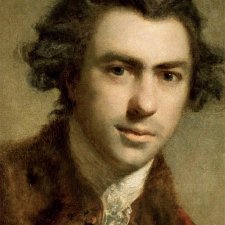

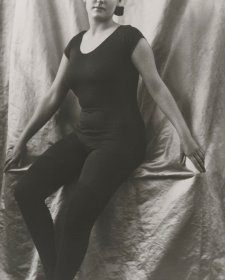

Wild also went London promoters enticed by Kellerman’s ability to meld masculine strength with a winking awareness of the appeal of the womanly body she displayed to great effect in tight fitting costumes. The amount of leg exposed by the style of swimming costume she chose to wear raised eyebrows to the extent that, when called on to perform for members of the Royal family, Kellerman was forced to concede something to decorum by stitching a pair of stockings onto her short, men’s style suit. In doing so, she invented the women’s one-piece swimsuit and created the full length black costume that became her signature, a look that enabled close inspection of her firm, lissom frame without risking the exposure of too much flesh. It was in this trademark suit that Walter Barnett photographed Kellerman in London some time before her departure for the United States in 1907. A leading portrait photographer of his era, Barnett (1862-1934) developed a speciality in portraits of celebrities with his Sydney business before moving to London in the 1890s, where his Knightsbridge address became the studio of choice for performers, artists, royalty and society figures. Barnett’s portrait of Kellerman typifies the celebrity aspect of his work and hints at his close relationships with fellow Australian expatriates. The portrait presents her as something of an ingénue, while its full length format also makes a feature of Kellerman’s athletic body and an allusion to her modern interpretation of new womanhood.

In her openness and ambition, and in not conforming to what she described as the ‘false reasoning’ of ‘short sighted moralists’, Annette Kellerman personified new ideas about female beauty and women’s rights – not the tightlaced, indignant feminism of the suffragettes, but an unbuttoned, energetic and assertive brand of femininity akin to Australia’s perception of itself in this era as young and progressive. Kellerman’s writing was infused with ideas about outdoor lifestyles and the beach which emerged with the rising popularity of swimming in the late nineteenth century. As a purifying activity to counteract the perceived evils of city life, or as an acceptably decadent and sensual pastime, swimming and beach-going entered the national imagination as typically Australian pursuits, embodying some of the ideas – health, energy and egalitarianism – that gained ground in the decades either side of Federation. Kellerman endorsed swimming as ‘a pleasure and a benefit, a clean, cool, beautiful, cheap thing we all from cats to kings can enjoy’ exclaiming that ‘the man who has not given himself completely to the sun and wind and cold sting of the waves will never know all meanings of life’.

Her lectures and guidebooks on health and beauty espoused swimming as a sport particularly suitable for women – an arena in which a woman could compete with or even outdo men while exhibiting herself in ‘all her gracefulness’ and exerting a ‘desirable influence’ on her physique, making ‘the thin woman fat and the fat woman thin’ with just the right kind of ‘body smoothness’. Kellerman’s advocacy of swimming helped liquefy the strictures of public decency applied to women, dismissing the attitude that saw them ‘imbued with the idea that it is most unladylike to be possessed of legs or to know how to use them’, and is said to have counted her role in emancipating women from the ‘chains’ of neck-to-knee swimming costumes as her greatest achievement. But she is perhaps more intriguing for her strident assertions ‘of woman’s right and duty to be beautiful’ and her railing against the ‘perverted moral code’ that equated a woman’s cultivation of physical attractiveness as the exertion of her charms ‘to no good ends’. Her first text encouraging women to achieve fitness and a fine physique was the self-published Health, Beauty and Happiness (1909), a booklet detailing a course of instruction that would, ‘with absolute certainty’, make one’s figure as perfect as hers while also eliminating flaws as various as bad skin, poor circulation, backache, indigestion and ‘torpid liver’. Physical beauty: how to keep it and How to swim – illustrated with try-this-at-home photographs of Kellerman in a series of yoga-like exercises – instructed women in the achievement of a new type of female beauty, freed from ‘fiendish’ corsets in a physical ideal that celebrated athleticism and the confident, unashamed and unadorned display of the body.

By the time her books were published, Kellerman was an international celebrity whose stage performances combined swimming, theatre and tips on health and beauty. In the United States from 1907, she worked in vaudeville for over two years before trying movies. She played the leading role – a mermaid called Annette – in her first film, Neptune’s Daughter (1914), achieving kind reviews for her swimming, dancing, and the acting which made ‘the character of the sea-god’s daughter a living personality’. Several other films followed, but A Daughter of the Gods perhaps best cemented her notoriety, containing what some have described as film’s first glimpse of a naked leading lady and featuring scenes where Kellerman appeared clad in little other than artfully-deployed lengths of her dark hair. The many photographs of Kellerman taken in the 1910s and 1920s are more consciously theatrical or flirtatious in flavour. More knowing of the smooth and saucy quality of her body, images of Kellerman in this era shift from glamourised portraits that dwell on her exotic, dark-eyed looks and dramatic persona to the postcards and publicity shots of her in theatrical poses or demonstrating dance moves and high-wire techniques. Images of her blacksuited body in exercise positions persisted along with the fame of her fine feminine form, although Kellerman quipped she was perfect only ‘from the neck down’ and is said to have preferred being photographed in profile.

A teetotaller and lifelong vegetarian, later in life Kellerman ran a health food store in California and worked with the Red Cross during World War 2, entertaining troops and convalescent veterans with routines combining high kicks and a piano accordion. Kellerman returned to Australia permanently in 1970 and swam regularly up until her death, in relative obscurity, in 1975. She has since been commemorated in the name of a swimming pool in her home suburb of Marrickville and as the buxom central figure in Wendy Sharpe’s murals at the Cook & Phillip Park pool in Sydney. Whether A Daughter of the Gods lived up to the sort of hyperbole it generated is a matter of conjecture as, with almost all of the films Kellerman made, it no longer exists in its complete form. The remaining stills and fragments of footage nevertheless add to the material culture of Kellerman’s fabulous existence – in the swimsuits, skimpy satin shorts, bikinis, mermaid suits, and sequinned stage costumes now residing in Sydney’s Powerhouse Museum, and in the international collections of images documenting her extraordinary and truly cinematic story.