It’s rare to see William Nicholas written about without reference to the Sydney Morning Herald’s description of him in 1847 as having ‘more heads offered to him for decapitation than he is able to take off’.

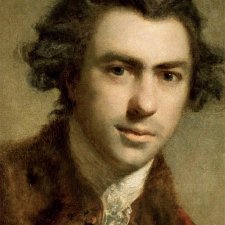

Born near London in 1807, William Nicholas is believed to have served an apprenticeship as an engraver and lithographer before immigrating to Australia in 1836. His arrival in Sydney coincided with a bump in demand for art fed by a growing population and the prosperity of cashed-up colonists keen to commission portraits as documents of success. Nicholas was soon in high demand, earning a consistent income in an era where portraitists outnumbered artists working in subjects such as landscape. At his studio residence on Elizabeth Street, Nicholas established a reputation as Sydney’s portraitist of choice, a catalogue of his surviving works often reading like a Who’s Who of Sydney society. Nicholas was commissioned by families like the Kings, Macarthurs and Wentworths who, like others of the time, used art to conceal ambiguities of birth, erase the whiff of convict origins, or make a statement about status and achievement. Portraits of possessions like houses, dogs, and horses were popular accoutrements of respectability, likewise an elegant portrait of one’s well-attired wife or child.

Into this mould fits a portrait by Nicholas of a girl named Alice Want, one of nine children of solicitor and politician Randolph Want. Alice’s portrait typifies the work for which Nicholas has remained best known: fine, deftly rendered watercolours which are often beguiling in their elegance and their evocation of Victorian-era drawing rooms and nurseries. The attention to the detail of Alice’s blue dress, down to the frills of her undergarments and the polish of her slippers, demonstrates the interest Nicholas’s portraits hold as a record of the fashions of his time. Lionel Lindsay, an early commentator on Nicholas’s work, described him as having drawn ‘the rustle of skirts’ for his livelihood, his studio providing an ‘attiring room’ for female clients to change into their finery. Works such as his exquisitely detailed group portrait of the children of an unknown Sydney family from the 1840s extend their attention to ringlets, ruches and bowties as well as the rosy cheeks, toys and pets which mark these as children of the wellto- do. These are intimate glimpses into the domestic world and telling expressions of the way Sydneysiders saw themselves in the middle decades of the nineteenth century.

Alice’s great-great grandchildren – Louise Dobson and Alice, Emily and Edward Simpson – have included her portrait in the selection of works recently gifted to the National Portrait Gallery in memory of their mother, Caroline Simpson OAM (1930-2003). A remarkable patron of the arts, Caroline Simpson built an extraordinary collection of art and objects that was both a significant record of colonial Australia and a document of family history. With the gift of Alice’s portrait and other works from the Simpson family collection, the National Portrait Gallery has gained a fine example of the work of a colonial portraitist along with a record of the family’s tradition of patronage of the arts in Sydney.