The idea for a National Portrait Gallery was first raised by a painter – his name was Tom Roberts - in the early part of the last century. Though best known nowadays for his landscapes, Roberts was also a significant portrait artist. He sensed the emergence of a distinctive Australian identity and saw the need to develop a collection of artworks to capture this. Fortunately, these views were shared by others.

At the time, Roberts, along with Arthur Streeton, was painting at his Collins Street studio in Melbourne, set up by Hugh Paterson, a fellow painter and its administrator. One of the regular visitors to this studio was the Prime Minister of the time, Labor Prime Minister Andrew Fisher. His office was literally next door. He liked to pass away the time and to escape the rigours of political office by spending time with artists. There, Malcolm, lies a reflection for both of us for the future.

The friendship between Andrew Fisher and Hugh Paterson led to several initiatives to promote the development of Australian art, like the establishment of an Historic Memorials Committee, an Art Advisory Board to commission Australian artists to paint prominent politicians and significant national events. These set the foundations for Australia’s national art collections and bring us to where we are today: standing between our own National Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery.

So what is a National Portrait Gallery? There are different examples around the world, and the directors of most of them are here tonight to welcome their Australian sibling into the family, this great, global family of national portrait galleries. Common to each is the panorama of history on display and the representation of women and men through the ages whose actions and deeds have contributed to the fabric of their nations and their societies.

A portrait gallery brings to life the arid pages of history. It reminds us of events, people, places often forgotten. It presents us with the faces, the flesh, the blood, the human spirit of real women and real men. Not great theories at work in international politics or the rise and fall of nations, but human beings – failed, flawed and great, and all at the same time.

Portraiture is important to memory, both collective and individual, and a nation without memory is a nation without soul. There are innumerable examples of great portraits presenting great people who’ve achieved great things – or others simply portraying an idea, a moment, an event or a person unnamed.

I’m sure we all have our favourite portraits. Hans Holbein, the Younger’s portrait of Sir Thomas More – unforgettable. The many portraits of Queen Elizabeth I, designed to show us her strength and power, and her ability to defend England against all its foes. Vermeer’s portrait of the Girl with the Pearl Earring, capturing the beauty of an unknown girl, yet leaving us with a sense of the vibrancy of youth and richness of life in Delft during the Dutch Golden Age. Contrast that with Rembrandt’s Self Portrait As An Old Man, indelible in the memory – once you’ve seen it once you never forget it - in which we confront our own physical decline or mortality. Or, more hauntingly, disturbingly Goya’s great image of the Third of May depicting the execution of young Spanish citizens who defended Madrid against the French. An image of fear and death, yet defiant pride, heroism and fervent nationalism.

Each of these portraits tells a story, a very human story, a very personal story. They tell us also of connected political and cultural events and in times and places which stir the collective memory. Which brings me to a second question: what is a portrait?

Portraiture, as the word suggests, is about portrayal. The capturing in a picture, a photograph, a sculpture, or video of something more than a person’s physical likeness – more than just a face. It reveals something of the psychology of the person. It reveals something of their spirit. A reminder of their great deeds, or the hardships that they’ve endured. It gives us a window into their everyday life, their physical surroundings or social context.

If you enjoy portraiture as much as I do, then the thing which often grabs me apart from the face which has been captured and the person who lies behind that face, it is usually the things which surround them in the picture. The artefacts of the age, the things which were nearest and dearest to their work-a-day lives. Great reminders of an earlier age, often a simpler age, but not always so. It reminds us also of their humanity, their vulnerability and above all their mortality.

Those great portraits with the human skull placed beside them on the desk, again a reminder of the mortality of politicians, I fear.

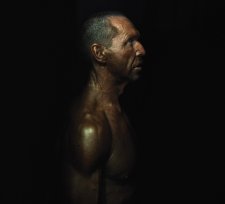

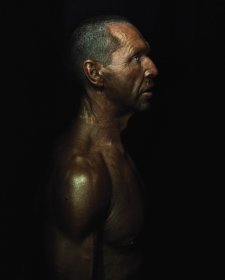

The portrait tells us more than who these people are – it tells us what they are. The National Portrait Gallery is a story of Australia and it’s meant to be an Australian story. The story of who we are. The story of where we have come from. The events, the ideas and the forces that have shaped this thing called an Australian identity. The people who make us Australian in all of our wonderful diversity.

Our National Portrait Gallery paints the great sweep of Australian history, starting with Indigenous Australians. The images given to us by Indigenous Australian artists tell us of their place on this continent, on this - their continent. Of their relationship to their surroundings; of their spiritual beliefs; of their dispossession, their struggle, their past injustices as experienced from we, the secular community.

At the start of the permanent collection we see Tituni posts which commemorate the dead from the Tiwi Islands. These objects are more than just decorated poles: they are Indigenous representations of people and of their being. They too are portraits.

Portraiture is an art from which we readily engage. As individual art critics, we have an opinion about how the artist presents their subject: if the likeness is accurate, amusing, pompous, fair or dignified; if the picture is one dimensional or if it tells us a wider story; and most certainly, whether the subject was even worth portraying in the first place. The National Portrait Gallery’s remarkable collection weaves together the different strands of experience from our national story. It connects us as Australians - sometimes in the most unexpected way.

One of the most powerful images in this gallery is a small black and white woodcut by Ludwig Hirschfeld Mack, who fled Nazi Germany only to end up in an internment camp for enemy aliens in Australia during World War 2. After the war he became head of the art department at Geelong Grammar School. His self portrait, made in the camp during the War, is of a solitary figure: incarcerated, trapped, powerless, staring at the night sky. With that wonderful symbol of Australian identity, struggle and the ability to overcome the odds - the Southern Cross – visibly painted overhead. His displacement, but connection to Australia, is replicated in an adjacent image by Indigenous artist Kevin Gilbert, himself in gaol when he portrayed the isolation of a group of Indigenous people looking at the night sky and that same potent symbol: the Southern Cross.

Most visitors will be amazed at the path of history contained within these walls, and also at just how up-to-date the collection is. There is literally something for everybody in the National Portrait Gallery: explorers, political figures, artists, musicians, singers, actors, comedians, sportsmen and women, bushrangers, writers, judges, scientists, immigrants, academics, well known Australians, unknown Australians. And that is as it should be, because that is the Australian family. Some of the works are challenging and thought provoking; others are just amusing and plain fun.

One of the more famous - Perished, artist Sidney Nolan’s representation of the doomed Burke and Wills expedition - shows the explorer finally having succumbed, sinking in death back into the harsh Australian landscape. It is an arresting work. Robert Hannaford’s most moving portrait of Lowitja O’Donohue, shows us the face of dignity, wisdom, experience and great sadness. Lowitja, it’s good to have you with us. Lewis Morley’s hilarious portrait of Dame Edna Everage, photographed as Christine Keeler from the scandalous 1960s: there is a mental image best purged from your mind. Or how about the iconic image of singer Nick Cave?

There are many ideas on display in this building: the struggle against nature and the harsh landscape; our determination and success across all fields of endeavour; creativity and resourcefulness; our fight against injustice and for fundamental fairness and human rights; the idea of Australia as a collection of unique individuals who all should have the opportunity to contribute to this unique nation.

Put together, the collection is about all of us. It’s about Australia, writ large in all of its diversity and in all of our national imperfection. The National Portrait Gallery is a welcome addition to the parliamentary triangle, providing another piece to Walter Burley Griffin’s vision for significant national cultural institutions to reside within this precinct. I believe Griffin would be happy tonight to see this great building in his great triangle. This vision for Walter Burley Griffin’s triangle is yet to be completed. There’s more work to be done. But this building within this triangle is quintessentially Australian. It is a shining example of Australian national design and workmanship and contains building materials – timber and stone - from each State and Territory.

The architects have created an inviting gallery on a human scale that ties in well with the natural surroundings. The use of light and glass creates an open feeling and allows us to glimpse the Canberra landscape as we move between rooms. In this way, the building feels natural and easy to move through. A gallery that you want to walk into, where you feel comfortable once inside. Not overwhelmed, not intimidated – a place where you’d like to spend a bit of time. In that sense, this is a very Australian place.

When Andrew Fisher, Labor Prime Minister of a hundred years ago, and his circle of artist friends from the Heidelberg School started to talk about the development of an Australian vernacular art form, Canberra was not a reality, let alone any place to house such a collection. Much has happened in a hundred years, as we’ve built the Australian nation, and built great national institutions, such as this great national gallery. So many years later, we now have a gallery which presents the story of Australia’s identity, Australia’s history, Australia’s creativity, Australia’s culture, and all through portraiture.

I congratulate each and every one who is here this evening who has given birth to this idea, but most critically, has seen the idea through – each and every one. This has been an extraordinary project and I congratulate the resilience in seeing it through to this marvellous completion. I now have great pleasure to declare open the Australian National Portrait Gallery. May this be a grand reflection in the future of the Australian national soul.