But, as author L P Hartley noted, ‘the past is a foreign country, they do things differently there’. People in the nineteenth century, when this death mask was cast, had a different attitude to death. Death was familiar, not sanitised and confined to hospitals but, like births, more likely to occur in the home as part of family custom and ritual. Images of the dead were kept by the Victorians as treasured mementos but were also used in science. The study of skulls, bones and death masks supported nineteenth-century ideas of race, intelligence, personality and criminality. Phrenology, an area of forensic science that was based on an analysis of physiognomy, used facial features and the bumps and shape of the head as a guide to the moral and intellectual character of individuals. This ‘scientific’ discipline was becoming popular when artist and engraver Thomas Bock (1790–1855) was transported to Tasmania in 1824.

Bock arrived in time to witness one of the most sensational trials ever to take place in the in the colony of Van Diemen’s Land. Alexander Pearce was a thief transported for stealing six pairs of shoes. He proved himself a malcontent and was sent to Sarah Island on the West coast of Tasmania, one of the most remote and rugged areas in the world. In 1822, together with eight companions, Pearce escaped into the rugged bush. Two of the convicts died of exhaustion but the others killed and ate their fellows until only Pearce remained. When he was eventually recaptured, the authorities wouldn’t believe his incredible story, assuming he was protecting his still at large companions. Returned to Sarah Island he soon escaped again, taking Thomas Cox, another convict, with him. He was alone when he surrendered but his captors made a gristly discovery: he had human flesh in his pocket.

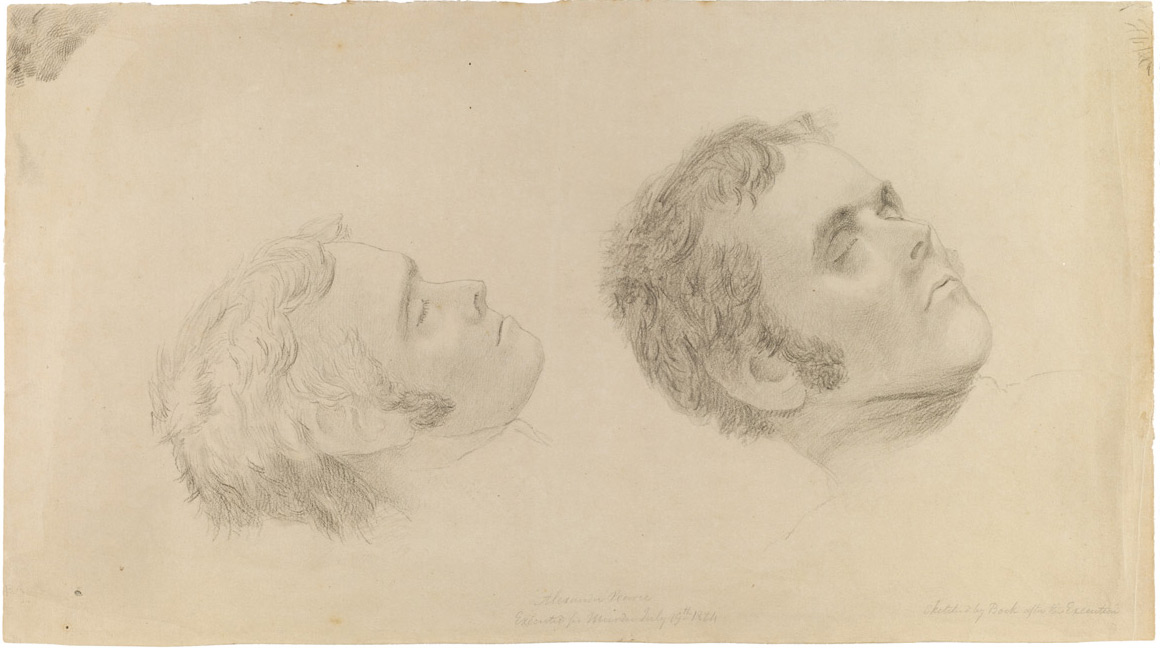

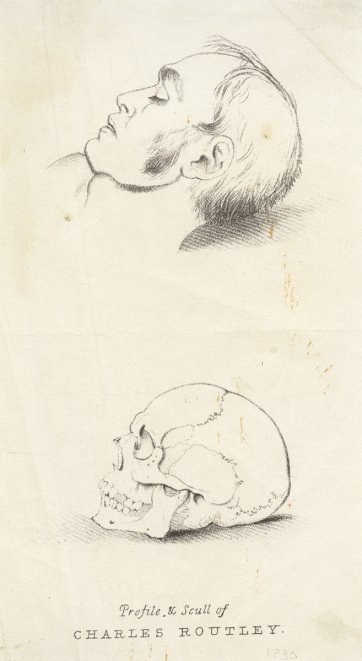

Pearce was found guilty of murder and hanged at the Hobart Town Jail on 19 July 1824. His body was handed over for scientific dissection and Bock was asked to draw the dead cannibal. He drew several sketches of Pearce, including two views of on a single sheet. It was certainly the chance to make a name for himself and the bottom right-hand corner bears the inscription ‘sketched by Bock after the Execution’. Keen to get ahead in the new land, Bock took on many jobs. He drew prisoners and captured bushrangers, documenting as might a court reporter, the features of the criminal classes. Another executed criminal, Charles Routley, was the subject of a print, this time pairing the dead man’s head with his skull. Bock didn’t want for work as Lieutenant- Governor Sir George Arthur who, like Bock, had arrived in Hobart in 1824 to take charge of Van Diemen’s land, imposed a severe law and order policy that produced an average of one hanging a week for two years.

Within a year Bock had proved his worth to the colony and was given a job at the Bank of Van Diemen’s Land engraving notes; his exemplary conduct eventually earning him a pardon in 1831. By then he had begun to advertise himself as a miniaturist and portrait painter, as well as offering lessons in painting. Art was practiced as a leisure activity by the middle classes and there were a number of gifted amateur painters in the colony, such as Mary Morton Allport (1806–1895) and Thomas Lempriere (1796–1852) whose portrait of Captain Kinghorne has just been acquired for the collection. Bock was the first professional painter in Tasmania and he thrived under successive governors Arthur and Franklin, producing many paintings and drawings of wealthy settlers. Lady Jane Franklin commissioned him to paint portraits of the Aboriginal peoples and Bock’s fine watercolours show his characteristic sensitivity to individual personality.

One such example is a delightful portrait of seven-year-old Mathinna (now in the collection of the Tasmania Museum and Art Gallery), who was living at Government House with Sir John and Lady Franklin in 1842 when this delicate watercolour was made. A friend of the Franklin’s daughter Eleanor, Mathinna was described as having ‘the manners of a well-born child’.

A year later the Franklin’s left the colony and Mathinna was sent to the Queen’s Orphan School in Hobart. The remainder of her life typifies the sad story of an individual caught between cultures. She died aged just twenty-one.

Bock produced many exquisite drawings such as this. Paintings were considered the finest expression of portraiture but Bock’s drawings, an economic and relatively quick form of portraiture, are very rewarding. Bock moved away from the detailed approach he had learnt as a miniaturist and loosened his style, responding to the broader fashion popular in London. He began using black crayon on buff paper with judicious touches of white and colour to provide highlights. His Woman in a black bonnet, thought to be Miss Georgina Butler, is a good example of this. The drawing is highly finished yet retains an informality and freshness. The dress and bonnet have been described in broad strokes picked out with white body colour, particularly on the lace coif, making an effective contrast with the carefully depicted facial features which the artist has modelled with a fine pencil and watercolour.

While this portrait is worked up almost to the level of a painting, other drawings loosely capture the sitter in a few select and virtuoso strokes – Little girl with curls is a particularly charming example. Bock has used the simplest of strokes and smudges of the black chalk to evoke the innocence of youth, enlivening the face with the barest touches of white on the light-catching features, the lips, forehead and nose.

When he arrived in Van Diemen’s Land, Bock was a penniless convict and took on any job that was offered, be it recording the features of outlaws, or engraving banknotes, almanacs and business cards. Despite the stain of his past Bock managed, by dint of his own endeavours, to build a reputation as an artist with a flair for portraiture. He set up his own gallery and built a clientele, slowly at first, but by the 1840s he was in demand for painted and drawn portraits. By the end of the decade he was one of the first to start using daguerreotypes, a new photographic process, to make portraits. Bock’s story charts the history of the colony from its violent start to genteel prosperity. It is also a history of portraiture in the transition from rude beginnings to professional studios, but above all it is a very Australian migration history. Bock’s personal history as a transported convict to successful society artist is the inspirational and part of the rich weave of histories that are the backdrop to the National Portrait Gallery.