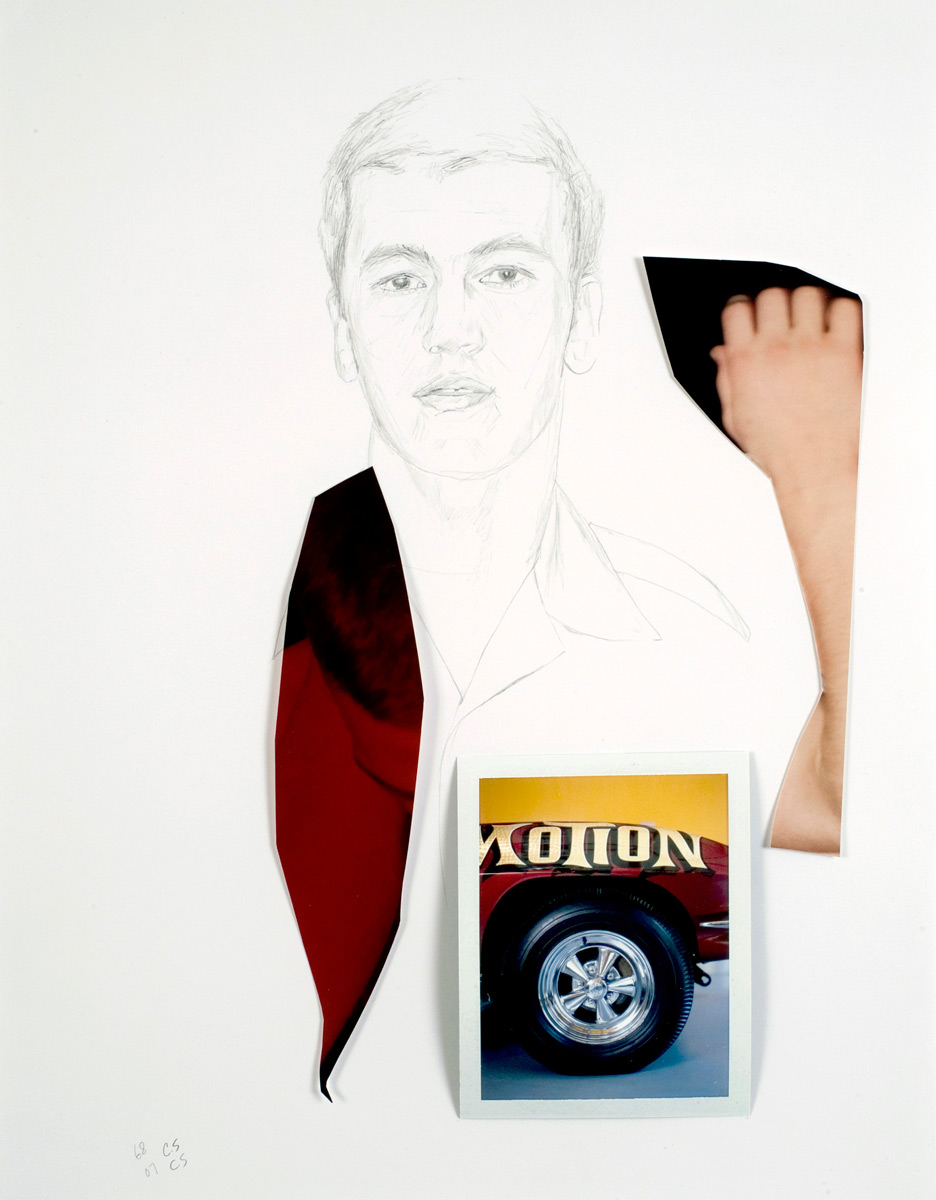

In 1968 Schorr’s father, a photographer for an auto magazine, travelled to Queens, New York, to do a story on the young racer and discovered that Charlie was about to be posted to Vietnam where he was killed in action a month later. Collier Schorr, then four years of age, accompanied her father to the racing track where he photographed Charlie’s car but she realised, as an artist working now, that it was impossible for her to document Charlie’s life directly as it was. Working from photographs that her father had taken of Charlie with his car, photographs that Charlie took on his tour of duty in Vietnam, and ‘official’ reportage of the Vietnam War, Schorr’s 2007 exhibition at New York’s 303 Gallery included photographs and drawings, displayed together as a group of elements that suggested a narrative about Charlie’s journey. Charlie as he was 2007, a singular work composed from graphic and photographic collage elements creates a portrait of Charlie that is inconclusive. It draws together symbols of Charlie’s identity as imagined by Schorr. Her knowledge of his status as a racer is signalled by the photographic detail of Ko-Motion, to which Schorr adds abstract collage photographic elements with a sketched portrait in which Charlie quietly meets our gaze. There is something gentle and elegiac about Schorr’s portrait. In its fragmentary and evocative visual construction it suggests an aspect of the fleeting quality of Charlie’s own experience. Once we have gained some knowledge about the sitter, the work takes on a poignant quality, and begins to engage a symbolic register that recognises the many young women and men who continue to die in war. The portrait speaks compassionately about loss.

Schorr attempts to assemble an idea of Charlie’s identity from separate elements, in the process conveying an atmospheric sense of Charlie as an individual. There is an impressionistic attitude at work, akin to the recent representation of US musician Bob Dylan in Todd Haynes’ 2007 film I’m not there. In the film six actors, including a woman (Cate Blanchett) and an African American boy (Marcus Carl Franklin), represent different moments in the musician’s career and different aspects of his personality. There is a coincidental relation between the title of Haynes’ film and Schorr’s exhibition There I was, but both question presence in different ways (Charlie was in Vietnam, Schorr was not; Dylan is an implied figure in Haynes’ film). Importantly, the construction of identity that Haynes and Schorr present questions the singularity of identity and suggests that selfhood, instead, might be understood as the amalgam of parts, and that identity and selfhood are entirely fluid.

Where Schorr has made a portrait as a composite, other contemporary artists explore the construction of identity by creating symbolic personae. In her earlier work, Hong Kong-born, Melbourne-based artist Kate Beynon created a series of paintings and animated films featuring the character of Li Ji, a warrior girl from Chinese Jin Dynasty mythology. Using a distinctive visual style that made reference to traditional Chinese painting, contemporary animation and street art forms, Beynon constructed narratives for Li Ji in the mythological past and in the contemporary Australian present. Li Ji experiences both ‘past’ and ‘present’ incarnations, bearing out a contemporary experience of complex feminine and cultural identity. Recently Beynon has created a series of images that reflect and engage a powerfully defiant sense of female identity. Dragon spirit 2007, from this series, might be understood as a contemporary archetypal representation of Australian female identity. A complex tension is established in the works in this series: Beynon’s use of spray-enamel paint and Swarovski crystals applied to the paintings’ surfaces engage competing registers of cultural meaning, and her use of decorative elements is challenged by a forceful sense of femininity. The women that Beynon depicts are streetwise and determined, and resist the assumption of a singular genealogical identity.

In his work, Hong Kong-based artist Hiram To has explored media constructions of identity. In Higher (Dior-orDi) 2002 he presents himself in the role of a fashion model, dressed in a minimal and cool style exemplified by contemporary glossy magazine advertising. The manner in which this image is presented is striking: as a double life-size, three-dimensional lenticular transparency in a glowing red illuminated light-box. Based upon an advertisement for Dior’s men’s fragrance Higher, To’s image parodies the intoxication promised by the product itself, as well as the power of advertising to dictate desirable self-images. The artist has deliberately made the perfume flask into a symbolic anonymous object to represent the allure of all luxury goods. To’s image is a self portrait, he presents himself in the guise of a contemporary urban sophisticate while subtly satirising the desirable nature of this identity-type. In aping the form of the advertisement, the image compels us to read it in terms of consumer desire, and it is a shock to realise how easily we may be manipulated by the slickness of the invented persona it represents.

Sydney-born, Los Angeles-based artist TV Moore has worked across photography and film, and often takes on a performative role in his work. However, rather than simply ‘acting out’ characters, Moore’s presence serves as an investigation of individual and symbolic identity. Recently Moore has explored constructions of masculinity and Australian archetypal characters. In his 2006 photographic work W. J Wills, Moore presents himself as the nineteenth century English-born Australian explorer William John Wills; however, Moore’s portrait is an expansive one. In a statement that accompanied the 2007 exhibition at Sydney’s Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery where Moore first exhibited the work, he and his brother Greg wrote: ‘Each work has its roots in history, in a story. However the familiar figures, monuments and narratives from which they draw are reanimated and reformed. They become stand-ins, transgressions, forming a sort of cultural geography, unbound by time yet grounded by imagination.’ While working in Los Angeles, Moore recalled his interest in Australian artist Sir Sidney Nolan’s paintings of Burke and Wills, a theme Nolan explored from 1948. Moore was interested in the ‘spirit’ of Nolan’s depiction of the explorers and he represents Wills in a diptych, gazing into the distance. In making a mirror image, Moore suggests a sense of psychological complexity. The work takes on an existential gravity, as if Wills is contemplating his own individual responsibility or destiny. Like the other images discussed here, Moore’s work is compelling for the subtlety of its distinction between self and other, for its layering or amalgamation of individual attributes, and ultimately for its questioning of the concept of a singular or fixed individual identity.